| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

More Special Reports |

| Posted July 9, 2007 |

| Through a Prism of 40 Years, |

| Newark Examines Deadly Unrest |

|

|

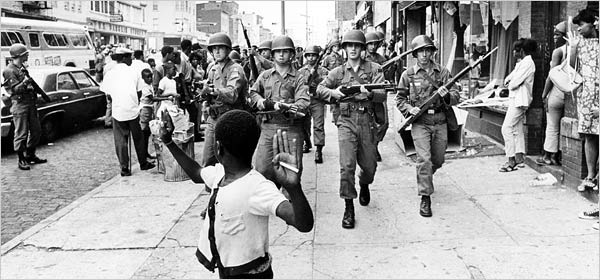

Don Hogan Charles/The New York Times |

|

| National Guardmen, with bayonets fixed on their rifles, advanced along Springfield Avenue in Newark on July 14, 1967. Twenty-three people were killed in rioting. More Images |

_____________ |

|

| 5 Days of Riots Driven | |

| By Race-Tinged Rage | |

By ANDREW JACOBS |

NEWARK, July 6 — Four decades later, many people here still cannot agree on what to call the five nights of gunfire, looting and flames that disemboweled the geographic midsection of this city, leaving 23 people dead, injuring 700, scorching acres of property and causing deep psychic wounds that have yet to fully heal.

To the frightened white residents who later abandoned Newark by the tens of thousands, it was a riot; for the black activists who gained a toehold in City Hall in the years that followed, it was a rebellion. Those seeking neutrality have come to embrace the word disturbance.

“There is not one truth, and your view depends on your race, your age and where you lived,” said Linda Caldwell Epps, president of the New Jersey Historical Society.

The society has planned a series of panel discussions and film screenings to mark the 40th anniversary of the violence, which began the night of July 12, 1967, after false rumors spread that an African-American cabdriver had been killed by police officers after his arrest for a traffic infraction. Avoiding the semantic controversy, the society has titled a planned exhibit “What’s Going On? Newark and the Legacy of the Sixties.”

There are no public monuments to mark the episode that painted Newark as a national symbol of racial disparity, police brutality and urban despair, but there is a newfound willingness here to confront the past. City officials, who ignored previous anniversaries, will dedicate a plaque Thursday at the Fourth Precinct station house, where the first skirmishes erupted between residents and the police.

“It’s still a touchy and contentious subject, but the fact that there is dialogue taking place is highly positive and would not have happened 10 years ago,” said Max Herman, a sociology professor at Rutgers University who has collected 100 oral histories about those five calamitous days. “I think for the first time Newark feels secure enough to turn back and look its history straight in the eye.”

Of course, that history is still open to interpretation.

For Junius W. Williams, who was a young law student at the time, the civic unrest paved the way for a golden era of black empowerment. But Sally Carroll, one of the city’s first black female police officers, looks around Newark and sees lessons that have yet to be learned. Although the riots marked the end of a thriving retail strip dominated by white merchants, Morris Spielberg, a furniture salesman, stayed put and thrived. Four decades later, Paul Zigo, a National Guardsman at the time, is still haunted by images of rage-filled rioters and the fatal shooting of a Newark firefighter.

“To me it was ironic that we were trained to fight an enemy overseas,” he recalled in a recent interview, “but we ended up fighting a civil disturbance in our own backyard.”

| An Agent for Change |

In 1967, Newark was a magnet for young militants from across the country who saw an opportunity in the city’s crumbling housing, its heavy-handed police force and a white-dominated government they saw as indifferent to the suffering of its black residents. Mr. Williams, a law student at Yale University, was part of this army of organizers who flocked to Newark, the state’s largest city, inspired in part by Tom Hayden, a founder of Students for a Democratic Society, who made it his base.

“I came here to be on the cutting edge of the movement,” said Mr. Williams, 63, the director of the Abbott Leadership Institute, a nonprofit group that promotes parental involvement in the public schools here.

That summer, Mr. Williams was organizing opposition to a huge urban renewal project that threatened to displace 20,000 impoverished residents with a new medical school. Among his comrades, there was also growing fury over the city’s refusal to investigate the killings of four black men who had died in police custody and simmering opposition to plans to evict thousands of people for a highway that would cut across the mostly black Central Ward. Tensions worsened when Mayor Hugh J. Addonizio appointed a white man without a college degree to the Board of Education, bypassing the state’s first black certified public accountant.

Against this backdrop of discontent, it was little surprise that residents reacted explosively to rumors that John Smith, the black taxi driver, who had been dragged by officers from a squad car into the Fourth Precinct station house, had died (although he actually had been taken to a hospital with minor injuries). That evening, a crowd gathered outside the station house, throwing stones and Molotov cocktails.

Fearless and fired up, Mr. Williams said he spent the next two days driving around the city trying to document what he saw and, at one point, was stopped with a carload of friends by a group of officers with their guns drawn. “To this day I don’t know whether the sergeant was pro-life or thought he couldn’t get away with shooting a law student," he said.

Mr. Williams, who had grown up in Virginia, stayed after the fires died down, believing that what he called “the rebellion” could be harnessed for positive change. In the months and years that followed, he led groups that won a series of concessions from the city and the state: An apprenticeship program funneled hundreds of black men into the construction industry; the medical school campus was scaled back to 60 acres, from 150; and the Newark Housing Council was given the task of building 1,000 apartments for those displaced by urban renewal.

“When we sat down at the bargaining table, an unnamed person sitting with a brick was with us,” he said. “The most important weapon was that there had been a riot and the powers that be were afraid of us. They would do anything to keep a lid on black anger.” Those were heady days, capped by the election of Kenneth Gibson in 1970 as the city’s first black mayor. But the euphoria was short-lived, at least for Mr. Williams. He said that he was infuriated when the authorities did not indict anyone in the killings over those five days, and that the energy and optimism of grass-roots organizers were moderated as they joined the establishment. He, too, served in the Gibson administration, until he was fired after clashing with the mayor.

“A lot of people thought all we had to do was get rid of the white racist people and everything would get better,” he recalled. “We thought it would happen overnight, but we were wrong.”

| A Businessman Who Held Out |

Conventional wisdom says that the riots drove away Newark’s white residents, but the truth is that they had been heading to the suburbs for decades. By 1967, more than half the 363,000 white people who had lived here in 1950 were gone; during the same period, the city gained 150,000 black residents, many from the South, according to census figures.

Even after moving out, white merchants like Morris Spielberg, who lives in Verona, continued to earn a living along vibrant commercial boulevards like Springfield Avenue. Once the heart of the city’s Jewish quarter, by 1967 it had become a neighborhood dominated by African-Americans in decaying wood-frame houses. Mr. Spielberg, now 83, owned two furniture stores that sat opposite each other and was president of the Springfield Avenue Merchants Association, whose members watched nervously as racial disturbances flared up in other American cities.

“We had no police protection, and the city didn’t care,” Mr. Spielberg said.

Over those five violent days, the Jewish-owned stores on Springfield Avenue and Prince Street bore the brunt of the raging mob: Metal security gates were wrenched out, windows were shattered and anything portable was carted off. Mr. Spielberg said he escaped one of his stores, Almor Furniture, thanks to the quick thinking of a black employee, who beseeched him to lie on the back seat of his car under a blanket.

“I flew 35 bombing raids during the war,” Mr. Spielberg recalled. “I was hit over Germany. But I was more scared that day in Newark.”

The next day he returned to watch as a man threw a steel trash basket through the shop window. He lost one of the two stores, but stayed to rebuild the business while many fellow merchants cashed in their insurance and left town.

“I didn’t want to be known as a Jewish rip-off artist,” Mr. Spielberg said, addressing the widespread belief, still common, that the neighborhood’s merchants had somehow stoked the mob. “I wanted to change people’s minds.”

An intense, wiry man who talks furiously with his hands, Mr. Spielberg was raised in an orphanage because his parents, Russian immigrants, could not keep their children fed. “My mother was on welfare, so I could relate to what these people were going through,” he said of the poor people who revolted that summer.

Mr. Spielberg insisted he accomplished some good by staying put all these years, by employing local residents, charging low rents to tenants in the five apartments he owned above the furniture store and simply by believing that Newark was a place worth saving.

“We were the guys who got kicked around and got called all kinds of names,” he said triumphantly. “But I’m still here.”

| A Heartbroden Soldier |

For years, Paul Zigo avoided this city, where he was born and where he nearly died.

But on Friday, Mr. Zigo, now a history teacher at Brookdale Community College in Lincroft, N.J., drove 40 miles to the Newark intersection where, as a National Guard lieutenant, he took fire from an unseen assailant.

It was an emotional homecoming for Mr. Zigo, who was raised in the city’s Ironbound section and was celebrating his 24th birthday when he got a call to report to the Red Bank Armory for duty.

Mr. Zigo, who served in Europe during the cold war, remembered the jarring unease this time of being handed a weapon to be used against his own countrymen. As his battalion of 500 soldiers moved up the Garden State Parkway before dawn on Saturday, July 15, the men gazed in silence and disbelief as Newark’s skyline shimmered in the orange glow of a city in flames. “It was the most tense and fearful days of our lives,” he said.

The men were assigned to stand along the barricades that were supposed to contain the lawlessness to the city center; except for families clearly seeking refuge, no one was allowed to leave, and no one could enter. The peril came when the men traveled from those fixed posts to the National Guard headquarters at a nearby high school. Bullets flew overhead, Mr. Zigo recalled, and he said that on one occasion, he had to flee a crowd of angry residents in his Jeep.

He insists that the dead were felled not by guardsmen, but by local and state police officers, whose job it was to go after looters. “We were ordered not to return fire unless we knew who was shooting at us,” he said.

Saturday evening, Mr. Zigo was in a convoy in the Central Ward when a fusillade forced the guardsmen out of their unarmored vehicles. It was then, he said, that someone fired directly at him from a blacked-out bank, missing by a foot. A few minutes later, someone in the building pulled a fire alarm. Two firefighters arrived and broke into the building. As the guardsmen stood watching, a burst of gunfire rang out. One of the firefighters, Michael Moran, fell dead. “It happened so quickly, it is still hard to comprehend,” Mr. Zigo said with sadness in his voice.

An investigation never determined who killed Mr. Moran, although initial reports blamed the police for the shooting.

The following day, Mr. Zigo was at the Newark Armory when Gov. Richard Hughes declared the unrest contained and ordered the guardsmen home. There was no cheering, no elation, Mr. Zigo recalled, just relief.

“When we walked out of the armory, a lot of us wept,” he said. “I cried, too. I was just full of sorrow.”

| An Officer and an Activist |

Sally Carroll was in Boston, riding up a hotel escalator when a man riding down yelled out the news: “Newark is on fire!”

Born in Virginia, Ms. Carroll had spent most of her life in Newark’s West Ward. As an adult, she straddled the worlds that collided in her city that week: she worked as a law enforcement officer and had recently been elected president of the Newark chapter of the N.A.A.C.P.

She was in Boston that day for the group’s convention, but drove back home the next morning, in part to make sure the local N.A.A.C.P. office stayed open for people who needed help; at first, she said, the car was blocked from getting off the highway to enter Newark.

“It was scary coming back into the center of the city,” Ms. Carroll said, recalling the smell of fire and the sound of gunshots. “So much destruction and chaos.”

But in a telephone interview from the home she has lived in since 1952, Ms. Carroll, now in her late 80s, said the unrest was not a complete surprise.

“At that point, relations between the black community and the police were at a pretty low ebb,” she recalled. “White people were feeling very put upon, and we had a lot of complaints in the N.A.A.C.P. about police brutality, and police callousness as far as treatment of black folks.”

Ms. Carroll started as a Newark police officer, and by 1967 was a detective in the warrants squad of the Essex County Sheriff’s Office. But, having taken vacation days for the N.A.A.C.P. convention, she spent the five days of the riot wearing her N.A.A.C.P. hat.

The courthouse, she said, was an “armed encampment,” overflowing with people who had been “arrested willy-nilly, just scooped off the streets.” At the armory one day, she ran into Mayor Addonizio, who she said “had always been dismissive of complaints about police misconduct.”

“He had always been a jaunty, debonair kind of guy,” she said. “When I saw him at the armory with Governor Hughes, he looked tense, and very old.”

Ms. Carroll worked in the sheriff’s office until 1977, and then became the first woman appointed to a full-time position on the state’s parole board.

“Nobody was ever indicted in any of the killings,” she noted. “And some of them were just so unreasonable. A guy going to put his garbage out, shot in the street.”

Kareem Fahim contributed reporting.

Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, New York Report, of Sunday, July, 8, 2007.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |