| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

More Special Reports |

| Posted October 24, 2005 |

| What's He Really Worth? |

|

| For decades, Donald Trump, America's most effervescent rich guy, has made his wealth a matter of public discourse. But sometimes his riches are hard to find. This article was adapted from "TrumpNation: The Art of Being the Donald," by Timothy L. O'Brien, a reporter for The New York Times. The book, to be published on Wednesday by Warner Books, looks inside Mr. Trump's wallet. |

| ______________________ |

By TIMOTHY L. O'BRIEN |

| ______________________ |

BY 1993, with his casinos in hock, most of his real estate holdings either forfeited or stagnant and his father slipping into the fog of Alzheimer's disease, Donald Trump, at the age of 47, had run out of money. There were no funds left to keep him aloft, and as the bare-bones operation he maintained in Manhattan started to grind to a halt, he ordered Nick Ribis, the Trump Organization's president, to call his siblings and ask for a handout from their trusts. Donald needed about $10 million for his living and office expenses, but he had no collateral to provide his brother and sisters, all three of whom wanted a guarantee that he would repay them.

The Trump children's anticipated share of their father's fortune amounted to about $35 million each, and Donald's siblings demanded that he sign a promissory note pledging future distributions from his trust fund against the $10 million he wanted to borrow.

Donald got his loan, but about a year later he was almost broke again. When he went to the trough the second time, he asked his siblings for $20 million more. His brother Robert Trump, who briefly oversaw Donald's casinos before fleeing the pressure of working for him to take over their father's real estate operation, balked. Desperate to scrape some money together, Donald tasked Alan Marcus, one of his advisers, to contact his brother-in-law John Barry and see if he could intervene with Robert and his other siblings.

"John and I spoke about it a few times," Mr. Marcus told me. "In fact, we spoke about it in the conference room in Trump Tower. John then went around and addressed it with the family."

Mr. Marcus said that Mr. Barry successfully lobbied other members of the Trump clan and that another handout was arranged, with Donald agreeing again that whatever he failed to pay back would be taken out of his share of their father's estate.

"We would have literally closed down," said another former member of the Trump Organization familiar with Donald's efforts to keep the company afloat. "The key would have been in the door and there would have been no more Donald Trump. The family saved him."

Donald disagreed with this version of events. "I had zero borrowings from the estate," he told me. "I give you my word." Donald's brother, Robert, did not respond to repeated interview requests. Mr. Barry is deceased. His widow, Maryanne Trump Barry, a federal judge, said that she could not recollect any efforts to offer her brother financial help. Donald's other sister, Elizabeth, was unavailable for comment.

But Mr. Marcus and two other executives who worked closely with Donald all said the family's financial lifeline gave the developer the support he needed to get through the rough waters separating his early years of overblown, overhyped acquisitions and the later years of small, sedate deals preceding his resurrection on "The Apprentice." Both of Donald's parents died during that time, he parried with Ivana Trump in a bitter divorce battle that hinged on properly valuing his dwindling assets, he remarried and divorced again, and then he did what anyone else in his situation would do when confronted with limited options: he ran for president of the United States.

Before Donald could get to Phase 2 of his career, he had to muscle his way through the dismantling of his business empire and a thorny financial restructuring with his bankers and bond holders that left him on the precipice of personal and corporate bankruptcy. As bankers who once fell over one another to throw money at him now lined up for their share of what was left over, Donald scrambled to hang on to whatever he could while maintaining his facade as America's most savvy entrepreneur. And in terms of maintaining his popular mojo, Donald proved remarkably resilient.

|

|

|||

Neal Boenzi/The New York Times |

||||

"When I was in trouble in the early 90's, I went around and - you know, a lot of people couldn't believe I did this because they think I have an ego - I went around and openly told people I was worth minus $900 million," Donald recalled. "And then I was able to make a deal with the banks."

To survive a process as tortuous and unpredictable as a debt workout, however, requires a large dose of gumption. Donald had gumption in spades. "You're out there alone. I mean, it's not fun," he advised me. "I went from being a boy wonder, boy genius, to this [expletive] guy who has nothing but problems."

Although Donald's brush with bankruptcy separated him from some of his showiest assets and from the banks whose loans had first puffed him up, his penchant for claiming billionairedom remains. To this day, he closely monitors his ranking on Forbes magazine's annual list of America's wealthiest individuals, the Forbes 400, and his ability to float above the wreckage of his financial miscues and to magically add zeroes to his bank account has ensured that he remains an object of fascination. But how much is Donald Trump really worth?

IN September 1982, with Trump Tower a year away from completion, Forbes published the Forbes 400 for the first time. (In 1918, Forbes produced a list of America's 30 richest people, but that was a one-time event.) Chock-full of anecdotes about how the rich became rich and what they did with their richly deserved riches, the Forbes 400 was financial pornography of the most voyeuristic and delicious sort.

While there was a refreshing inclusiveness about the list (Mafia treasurer Meyer Lansky made the inaugural tally, for example), some on the roster held rank upon the loosest of foundations. For those whose wealth was based on a stake in a publicly traded company, calculating their Forbes worthiness was relatively straightforward: put a value on their stock.

But for those with privately held money who weren't a Rockefeller, Mellon, du Pont or Kennedy, the process of ascertaining fortunes was trickier. Forbes relied on those people to willingly fork over an honest and somewhat exact self-appraisal of their wealth.

It also turned out that some big buckaroos, understandably averse to receiving an avalanche of phone calls from charities or scamsters that would follow such publicity, loathed being on the list. Nonetheless, the Forbes 400 drew scads of attention from the moment it was published. The list became capitalism's Rosetta stone, a decoding device for divining the American Way. Even prominent economists parsed it for social truths.

"At a trivial level, it is almost impossible not to be interested in Forbes magazine's annual list of the 400 wealthiest individuals, minimum net worth $150 million, and 82 wealthiest families, minimum net worth $200 million," wrote Lester Thurow, an M.I.T. economist, in 1984. "Subconsciously, we read their biographies hoping to find the elixir that will add us to the list. While the elixir - a rich father - is to be found (all of the 82 families and 241 of the 400 wealthiest individuals inherited all or a major part of their fortunes), it doesn't help most of us to point this out to our fathers."

Professor Thurow added: "Great wealth is accumulated to acquire economic power. Wealth makes you an economic mover and shaker. Projects will happen, or not happen, depending upon your decisions. It allows you to influence the political process - elect yourself or others - and remold society in accordance with your views. It makes you an important person, courted by people inside and outside your family. Perhaps this explains why some people try to persuade Forbes that they are wealthy enough to merit inclusion."

This, then, was the dividing line: Those who were secure enough not to reveal their wealth abhorred the Forbes 400, or at least tried to avoid it; those who were less secure, needed to keep score and had their identities wrapped up in the concept of billionairedom turned the list into a white-collar fetish. For the latter group, to be off the Forbes 400 represented emotional and social exile.

Donald, paradoxically, was a loner who did not want to live in exile. He was obsessed with the Forbes list. And his propensity for inflation, matched with Forbes's aversion to hiring the sizable staff it might need to assess accurately the wealth of each of its designated 400, got Donald on the magazine's inaugural list in 1982. Forbes gave him an undefined share of a family fortune that the magazine estimated at $200 million - at a time when all Donald owned personally was a half-interest in the Grand Hyatt hotel and a share of the yet-to-be-completed Trump Tower.

Donald and the Forbes 400 were mutually reinforcing. The more Donald's verbal fortune rose, the more often he received prominent mentions in Forbes. The more often Forbes mentioned him, the more credible Donald's claim to vast wealth became. The more credible his claim to vast wealth became, the easier it was for him to get on the Forbes 400 - which became the standard that others in the news media, and apparently some of the country's biggest banks, used when judging Donald's riches.

IN some years, Donald insisted on impossibly high figures for his net worth and then, in a faux fit of complaining, settled for an estimate that Forbes convinced itself was conservative - even though it was often wildly high anyway. The one gap in this mating dance was 1990 to 1995, when Donald didn't appear on the list at all. Forbes was apparently so chastened by the $2.6 billion difference in its estimate of Donald's wealth between 1989 and 1990 that the magazine needed a six-year hiatus before it had the confidence to begin helping him inflate his verbal fortune again.

Forbes's odes to Donald and his father, Fred Trump, went like this over the years:

1982 Wealth: Share of Fred's estimated $200 million fortune. Forbes explains: "Consummate self-promoter. Building Trump Tower next to Tiffany's. Angling for Atlantic City casino." Forbes quotes Donald: " 'Man is the most vicious of animals and life is a series of battles ending in victory or defeat.' " While Forbes estimates that the family's fortune was over $200 million, it says that "Donald claims $500 million."

1983 Wealth: Share of Fred's estimated $400 million fortune. (Author note: Observe that although 1982 to 1983 was a particularly brutal recession year, the Trump family's real estate fortune doubles.)

| _________________ |

A rich guy who is not exactly shy about being on the Forbes 400. |

| _________________ |

1984 Wealth: Fred has $200 million; Donald has $400 million.

1985 Rank: 51; Wealth: $600 million. (Donald becomes a solo Forbes 400 act; Fred disappears from the list.)

1986 Rank: 50; $700 million.

1987 Rank: 63; $850 million.

1988 Rank: 44; $1 billion.

1989 Rank: 26; $1.7 billion. (Observe that Donald's wealth has grown by $1.1 billion during a four-year period when he was borrowing huge sums to buy money-losing properties.)

1990 Dropped from the list! Forbes explains: "In 1990 the rich have been getting poorer. Trump is the most noteworthy loser. Once a billionaire, Trump's net worth may actually have dropped to zero." (That makes things clearer. Was he ever a billionaire? Maybe his net worth just stayed the same? Maybe it always had been zero?)

1991 AWOL.

1992 AWOL.

1993 AWOL. (These are the times that try men's souls. Hang in there, Donald.)

1994 AWOL.

1995 AWOL.

1996 He's back. Rank: 373; $450 million. Forbes explains: "Trump, polite but unhappy, phoning from his plane: 'You're putting me on at $450 million? I've got that much in stock market assets alone. There's 100 percent of Trump Tower, 100 percent of the new Nike store - they're paying $10 million a year in rent!' Add it all up, said Trump, and his net worth is 'in the $2 billion range, probably over $2 billion.' " (Don't worry, Donald. One year from now Forbes will help you find another easy $1 billion.)

1997 Rank: 105; $1.4 billion. Forbes explains: "Net worth was negative $900 million in 1990, but the Donald now claims to have $500 million in cash alone. Disputes our estimate. 'The real number,' he insists, 'is $3.7 billion.' "

1998 Rank: 121; $1.5 billion. Forbes explains: "Unstoppable salesman, master of hyperbole. Net worth was negative $900 million in 1990, now claims our estimate is low by a factor of three: 'The number is closer to $5 billion.' "

1999 Rank: 145; $1.6 billion. Forbes explains: "We love Donald. He returns our calls. He usually pays for lunch. He even estimates his own net worth ($4.5 billion). But no matter how hard we try, we just can't prove it."

2000 Rank: 167; $1.7 billion. Forbes explains: "In the Donald's world, worth more than $5 billion. Back on earth, worth considerably less."

2001 Rank: 110; $1.8 billion.

2002 Rank: 92; $1.9 billion.

2003 Rank: 71; $2.5 billion.

2004 Rank: 189; $2.6 billion. Forbes explains: "America's love affair with the Donald reaching impossibly new highs; his reality show, 'The Apprentice,' was prime-time television's highest-rated series last year ... After nearly defaulting on its debt obligations, Trump's gaming properties to reorganize ... No matter. For Donald, real estate is where his real wealth lies. Over 18 million square feet of prime Manhattan space."

Forbes, if not entirely skeptical of Donald, had, of course, grown accustomed to his intense lobbying. "There are a couple of guys who call and say you're low on other guys," said Peter Newcomb, a veteran editor of Forbes's rich list, "but Trump is one of the most glaring examples of someone who constantly calls about himself and says we're not only low, but low by a multiple." Mr. Newcomb said that Forbes works hard to ensure the accuracy of its data but that it also relies on information provided by those whom it surveys.

The Forbes 400, of course, has always loomed large in Donald's imagination.

"When you think of it, I've been on that list for a long time. I think they work very hard at the list," he told me. "It seems to be that they're the barometer of individual wealth. It doesn't really matter. It matters much less to me today than it mattered in the past. In the past, it probably mattered more."

Donald's verbal billions were always a topic of conversation whenever we visited. In my first conversation with him, in 1996, he brought up his billions. When Donald and I spent time together one weekend in Palm Beach, Fla., earlier this year, the subject inevitably came up. Donald had gamely and openly fielded a diverse range of questions all day, so I was curious to see where he would go when we got to money. When I popped the wealth question, he paused momentarily and scrunched his eyebrows. We had reached a crossroads. Out it came. He pursed his lips a little bit. Out it came. He blinked. Out it came, rising up from deep within him.

"I would say six [billion]. Five to six. Five to six," he said.

Hmm. The previous August he told me that his net worth was $4 billion to $5 billion. Then, later that same day that August, he said his casino holdings represented 2 percent of his wealth, which at the time gave him a net worth of about $1.7 billion. In the same day, Donald's own estimates of his wealth differed by as much as $3.3 billion. How could that happen? Was Donald living in his own private zone of wildly escalating daily inflation, a Trump Bolivia? And his $1.7 billion figure in August was well below the $2.6 billion that Forbes would credit him when it published its rich list just a couple of months later.

Now Donald was saying he was worth $5 billion to $6 billion.

"Five to six. Five to six."

And on the nightstand in my bedroom at Donald's Palm Beach club, Mar-a-Lago, was a glossy brochure that said he was worth $9.5 billion.

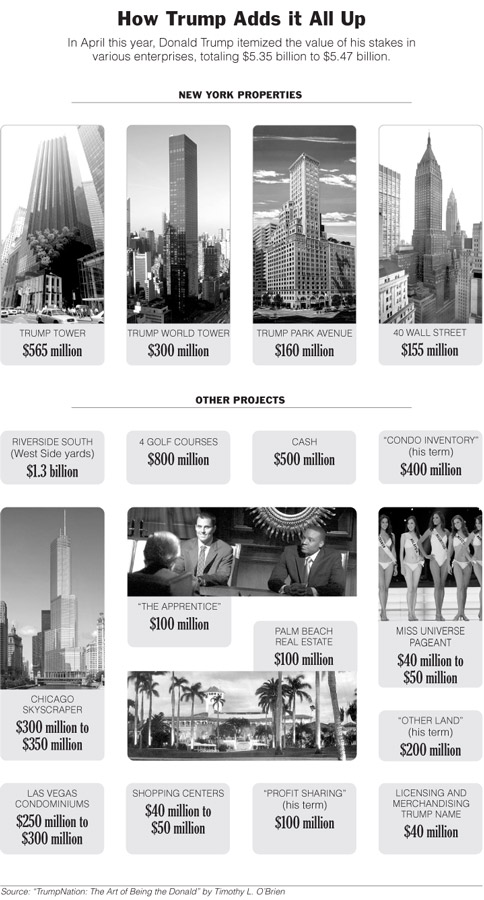

WHEN I sat down in a Trump Tower conference room one afternoon earlier this year with Allen Weisselberg, the Trump Organization's chief financial officer, he claimed that Donald was worth about $6 billion. But the list of assets that Mr. Weisselberg quoted, all of which were valued in very inflated and optimistic terms and some of which Donald didn't own, totaled only about $5 billion. Where might the rest have been? "I'm going to go to my office and find that other billion," Mr. Weisselberg assured me.

Did he ever return? No, he never returned. His assessment of Donald's wealth is outlined in the accompanying chart.

But Mr. Weisselberg's analysis left me confused. So I asked around for guidance.

Three people with direct knowledge of Donald's finances, people who had worked closely with him for years, told me that they thought his net worth was somewhere between $150 million and $250 million. (Donald's casino holdings have recently rebounded in value, perhaps adding as much as $135 million to these estimates.) By anyone's standards, this still qualified Donald as comfortably wealthy, but none of these people thought that he was remotely close to being a billionaire.

Donald dismissed this as naysaying.

"You can go ahead and speak to guys who have 400-pound wives at home who are jealous of me, but the guys who really know me know I'm a great builder," he told me.

However illusory, it was Donald's fixation on billionaire bragging rights and real estate prowess - in addition to the financial lifeline his siblings tossed to him - that kept his mojo rising during his brush with financial extinction in the early to mid-1990's. But the Donald who emerged on the other side of his business meltdown was a financial shadow of his earlier, acquisitive, debt-laden self, and would remain so right up to the debut of "The Apprentice."

Financial turmoil, of course, didn't stop Donald from spouting. The all-time howler award for a publication taking his verbal billions at face value belonged to Playboy. In early 1990, just a month before the Taj Mahal opened in Atlantic City and began a financial slide that would take Donald's empire down with it, the magazine profiled the developer and said he had amassed "a fortune his father never dreamed possible," including "a cash hoard of $900 million" and a "geyser of $50 million a week from his hotel-casinos."

In the real world, New Jersey casino auditors estimated in public reports that as of September 1990, Donald was worth about $206 million - almost all of which was tied up in hotels, an airline, casinos and other properties that were devaluing rapidly or about to be taken away from him. Donald's cash on hand was only $17 million, and that was dissolving quickly as well.

Regulators projected Donald's 1991 income from trusts and rentals at $1.7 million, offset by $9.7 million in debt payments, $6 million in personal business expenses and $4.5 million to maintain his Trump Tower triplex and estates in Greenwich, Conn., and Palm Beach for the year - meaning that he would be about $18.5 million in the hole at the end of 1991. Regulators projected Donald's income for 1992 to sink to $748,000 and his 1993 income to drop even further, to $296,000 - with all of his debt payments and personal expenses continuing to pile up. At the end of 1993, his personal cash shortfall would amount to about $39 million and there would still be $900 million in personally guaranteed loans hanging over his head.

In the midst of all of this, Donald reached a property settlement with Ivana Trump after their divorce. According to a 1991 New Jersey regulatory report, the settlement called for Ms. Trump to get a $10 million payment, the couple's Greenwich estate, $350,000 in annual alimony, $300,000 in annual child support, a $4 million housing allowance, use of some Trump properties and a $350,000 salary for running the Plaza Hotel. Donald didn't have the $10 million to pay his ex-wife; he ended up using part of the $65 million that banks had loaned his business the prior year to pay her, according to regulators who said in their report that the payment to Ms. Trump "depleted most of Mr. Trump's personal cash."

Throughout early 1991 and into the summer, Donald helped his banks begin to dismantle his holdings so he could pay off $3.4 billion in business debt and release himself from the $900 million in personal arrears attached to that pile. Absent an overhaul, Donald would be wiped out.

The little ray of sunshine in all of this for Donald was that the real estate collapse sweeping the country in the early 1990's left banks with wads of bad loans in their coffers. They could choose to put their borrowers out of business and be left owning companies they didn't want to run, or force debtors into messy bankruptcy proceedings that would involve paying whopping legal fees and suffering through years of delays. Neither alternative appealed to the banks.

"That was sort of the bottom of the heap. Deep trouble. They could have really done a big number. There was a personal guarantee on the loan," Donald told me. "My father was a pro. My father knew, like I knew, you don't personally guarantee. So I wrote a book called 'The Art of the Deal,' which as you know is the biggest of all time. In the book, I say, 'Never personally guarantee.' "

But, Donald added, "I've told people I didn't follow my own advice."

Donald's enthusiasm for the Forbes 400 also waned during his flirtation with bankruptcy. In his sequel to "The Art of the Deal," a book called "Trump: Surviving at the Top," he offered a new take on his view of a rich list to which he no longer belonged.

"It always amazed me that people pay so much attention to Forbes magazine," wrote Donald, who always paid a lot of attention to Forbes magazine. "Every year the Forbes 400 comes out, and people talk about it as if it were a rigorously researched compilation of America's wealthiest people, instead of what it really is: a sloppy, highly arbitrary estimate of certain people's net worth."

D ONALD managed to weather the slings and arrows of doubters during these lean years and hunkered down with his bankers and with his debts. As the negotiations progressed, Donald's bankers looked for every alternative they could find to bankruptcy, because none of the banks wanted to contend with the mess that would ensue if the talks collapsed. And the Trumpster kept singing a happy tune. "He was always upbeat," recalled Harvey Miller, a lawyer representing Citibank. "One thing I'll say about Donald, he was never depressed."

Unbeknownst to his creditors, Donald was just as worried about a bankruptcy as they were. He later told me that he wanted to avoid bankruptcy at all costs because he felt that it would permanently taint him as a failure or a quitter.

Sanford Morhouse, a lawyer representing Chase Manhattan bank in the Trump negotiations, said: "I did a lot of workouts in those days on behalf of Chase, with a lot of real estate developers who had similar problems, and big ones. Almost all of them, at one point or another in that era, filed for bankruptcy protection. And Donald, to his credit, did not."

Donald whittled down his mammoth personal debts by forfeiting most of what he owned. Chase Manhattan, which lent Donald the money he needed to buy the West Side yards, his biggest Manhattan parcel, forced a sale of the prized tract to Asian developers. Though Donald would claim after the yards were sold that he remained a principal owner of the site, property records did not list him as such.

According to former members of the Trump Organization, Donald did not retain any ownership of the site's real estate - the owners merely promised to give him about 30 percent of the profits once the site was completely developed or sold. Until that time, the owners kept Donald on to do what he did best: build. They gave him a modest construction fee and a management fee to oversee the development. They also allowed him to slap his name on the buildings that eventually rose on the yards because his well-known moniker allowed them to charge a premium for their condos.

Retained for his building expertise and his marquee value, Donald was a glorified landlord on the site; he no longer controlled it. (Earlier this year, the owners negotiated to sell the site without consulting Donald; terms of the prospective sale are in dispute.)

EVEN as the national real estate bubble was bursting, fresh funds began rushing onto Wall Street, fueling a historic run-up in both the stock market and initial public offerings of often barely viable companies. If you had a good story and a prominent name, it suddenly became quite easy to sell stock. And it turned out, against all odds, that investors were willing to gamble on Donald's name - even though they were getting a chief executive whose sense of his responsibilities as the steward of a publicly traded company and the guardian of other people's money was somewhat ill defined.

|

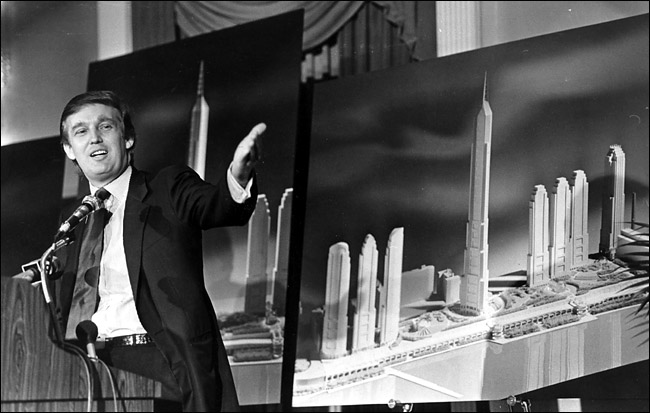

Neal Boenzi/The New York Times |

| Donald J. Trump, in 1985, announcing a plan for the West Side yards, which he then owned. He later lost control of the site in a debt crisis. |

"Something gnawed at me, and I knew what it was - the whole head-of-a-public-company routine," Donald wrote in "Surviving," relating his previous experience as a manager of Resorts International. "Although I certainly agreed with the theory of stockholder-owned corporations and was absolutely committed to fulfilling my fiduciary duties, I personally didn't like answering to a board of directors."

In a tribute to the sucker-born-every-minute theorem, Donald managed to take two of the Trump casinos public in 1995 and 1996, at a time when he was unable to make his bank payments and was heading toward personal bankruptcy. The stock sales allowed Donald to buy the casinos back from the banks and to unload huge amounts of debt. The offering also yanked Donald out of the financial graveyard and left him with a 25 percent stake in a company he once owned entirely. Trump Hotels and Casino Resorts traded at $14 a share initially and, along with a fresh bond offering, the new company raised about $295 million.

Exactly what investors thought they might get for their Trump Hotels investment wasn't entirely clear. Donald had already demonstrated that casinos weren't his forte, and investors were buying stock in a company that was immediately larded with debts that made it difficult, if not impossible, to upgrade the operations. Even so, Trump Hotels' shares rose to about $36 in 1996, giving Donald a stake worth about $290 million. With little real estate left to speak of in Manhattan, Donald's wealth was centered on his casinos.

But in subsequent years Trump Hotels' stock price tanked. Had Donald tried to pare down some $1.8 billion in debt smothering the casino company and spruced up the operation, he might have ridden a reignited gambling boom and grown his newly seeded fortune. Instead, Trump Hotels, which never earned a profit in any year between 1995 and 2005, became Donald's private stockpile of ready cash. In 1996 alone, Trump Hotels' shares fell to $12 from $35.50. About a decade later, the New York Stock Exchange delisted the shares entirely and any kid with a quarter could buy the stock. (Trump Hotels recently reorganized as Trump Entertainment Resorts; it now carries $1.2 billion in debt, and Donald's stake in the company is worth about $135 million.)

When I interviewed Donald in 1996, he was effusive about his casinos and somehow seemed to forget that he owned relatively little Manhattan property at the time.

"Donald Trump is in two businesses," he told me. "I have this huge company that's real estate. I also have this huge company that's gambling. So I have two huge companies."

Donald continued to carve out a niche for himself in New York real estate as the manager of other people's properties. In 1994, General Electric was looking for someone to refurbish the old Gulf & Western building on Columbus Circle in Manhattan, and retained Donald. Presto, the renovated skyscraper was christened Trump International Hotel and Tower. Even though Donald didn't own the building, it later flashed across the opening credits of "The Apprentice" as if he did.

And Donald did scramble back to gain control of some other Manhattan buildings, including 40 Wall Street, which he spent about $35 million to buy and refurbish in 1996. The building has about $145 million in debt attached to it, and New York City tax assessors currently value the property at about $90 million. Donald values it at $400 million.

Donald's recent golf course ventures have produced some sterling new properties, but the values he assigns those deals appear to be hyper-inflated. Donald's Palm Beach course, for example, has about 285 members who paid $250,000 for memberships, for a total of $71.25 million. Donald borrowed about $47 million to build the course and a new clubhouse. So he banked about $24 million on the deal, before other costs. He leases the land beneath the course from Palm Beach County; he doesn't own it. But Donald carries the course on his books as an asset worth $200 million.

Forbes, in bestowing a $2.6 billion fortune on Donald in its 2004 rich list, credited him with owning 18 million square feet of Manhattan property, which certainly is an impossibility. On one occasion, Donald told me that the West Side yards, which he doesn't own, would have 10 million square feet of salable space when the site, now known as Riverside South, was completed. (Mr. Weisselberg told me, alternatively, that the site would have about five million square feet of salable space.) However measured, the yards were by far the biggest property in Donald's former Manhattan real estate portfolio - but he no longer owned the tract.

Between 2000 and 2004, Forbes allowed Donald's verbal billions to grow by $1 billion. The jump came during a period when the stock market bubble burst, Donald's stake in his casinos - one of his most valuable assets until "The Apprentice" came along - had fallen in value to $7 million and, despite Manhattan's red-hot real estate market, he owned much less real estate there than he let on.

Donald said his casinos' myriad problems - no profits, suffocating debt, disappearing cash - did not mean that he had failed in Atlantic City. Instead, he described his management of the casinos as an "entrepreneurial" success, defining "entrepreneurial" as his ability to take cash out of the casino company and use it for other things.

"Entrepreneurially, not as a person who drives up stock, but as a private person, it's been a very good deal," he told me. "If I would have worked Atlantic City the way I worked real estate, I would probably be the biggest casino company in the world rather than just a nice company, et cetera, et cetera."

Two weeks ago, Forbes published its 2005 list of America's wealthiest people. Donald held 83rd place with what Forbes described as a $2.7 billion fortune. "My net worth has tripled," Donald told the magazine.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, SundayBusiness, of Sunday, October 23, 2005.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |