![]()

| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted June 25, 2003 |

|

Tribute to Chicago Icon and Enigma |

|

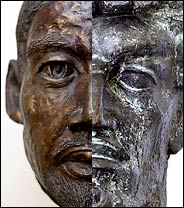

| Photograph by Peter Thompson for The New York Times |

| The undeveloped DuSable Park, north of the Chicago River, will honor Jean-Baptiste Point DuSable, as depicted by the bust above, who may or may not have been the sole founder of Chicago. |

By MONICA DAVEY |

CHICAGO, June 24 — How better to teach people, at last, about Jean Baptiste Point DuSable than to build and name a park for him right in the center of Chicago, his city, where the river meets the lake?

This leaves only one question: Jean Baptiste Point Du who?

DuSable is believed to have been the first non-Indian settler of Chicago, this city's William Penn or Peter Minuit. But even in the Chicago Historical Society's archives, people say they cannot be certain whether he really is the city's sole, true founder. Or when and where he was born. Or how he spelled his name. Or what he looked like.

And in a city that loves its history and has decided finally to give Du- Sable his due, by erecting a sculpture and etching his story in stone, this is a problem.

Most people agree that DuSable, a black man who spoke many languages, moved here and opened a trading post on the river's swampy north bank in the late 1700's, decades before Chicago was incorporated in 1833. There is little, though, in the way of written records, pictures and letters to flesh out DuSable's life. But the bare bones have been enough to make him a symbol, especially among black Chicagoans, who have been fighting since the 1920's to win him recognition as an emblem for the city and its diverse history.

In a city where racial rifts and ethnic pride run deep, DuSable, the black founding father, has long been tightly embraced, even with the gaps and mysteries in his biography. The struggle to define him can become "very passionate and very emotional," said Russell Lewis, the historical society's Andrew W. Mellon director for collections and research.

"There's just not a lot of historical documentation and facts about him," Mr. Lewis said. "When you get into the realm of speculation, historians tend to back off. But it is that very realm of speculation that draws other people to fill the void. He is a figure that many people want to own. Who gets to tell DuSable's story?"

Sometime soon, city officials planning the new DuSable Park will have to make some defining decisions about their subject. The latest sketches for the park, which will be a short walk down the river from where DuSable's trading post was, include a waterfall, a large sculpture and a plaza with historical information about him.

Faced with that sensitive duty, city officials did what city officials do. They appointed a committee.

The 15-member panel assigned to offer the city advice on its new park includes representatives from the advocacy groups that care deeply about all of this — the Chicago Du- Sable League, Friends of DuSable, the Haitian community, allies of the arts, and of the parks, and so on.

Dr. Serge Pierre-Louis, a committee member and president of the DuSable Heritage Association, said that committee members mostly agreed among themselves about the version of history to tell in this park: DuSable, who was most likely from Haiti, was the first non-Indian to settle here. He ran an elaborate trading and farming business near where Michigan Avenue crosses the Chicago River today. He married a Potawatomi Indian, Catherine, and got along with the Indians.

"There is no disagreement," said Haroon Rashid, president and founder of Friends of DuSable. The only issues, Mr. Rashid said, come from "new historians, who have come up with their spin." "People who are looking today to make the story different are trying to make a name for themselves," he said.

Others are less certain. Was it actually "Pointe DuSable" or "de Sable" or "Au Sable"? Was he really from Haiti? What year did he actually settle here?

John F. Swenson, a contributing editor to "A Compendium of the Early History of Chicago," said original documents showed that Point de Sable (the correct spelling, Mr. Swenson says) was more likely a British subject born in Canada who settled here in 1784 (not earlier, as others say) mainly as a farmer (not a trader). "It's not me that disagrees," Mr. Swenson said. "It's the documents that disagree."

Some records do tell his story, such as the long list of property, livestock, furniture, outbuildings and tools he sold in 1800 before moving south near St. Louis. Or the 1779 letter in which a British officer described DuSable as "a handsome negro, well educated and settled at Eschikagou," according to a draft of "The Encyclopedia of Chicago," to be published next year. Advertisement

Still, such records are rare. Few people were collecting historic documents about black people at the time, historians say, and besides, DuSable saw himself as an ordinary guy, not someone who was saving his receipts for the history books.

But the debate over details frustrates some, particularly those who fear that so many quibbles just diminish DuSable and his role in the city's history. The park itself has been years in the making, and even now money could be an issue. Mayor Harold Washington named the land for DuSable 15 years ago, but it has sat empty, growing tall grass.

The park appears likely to include a sculpture, but the Chicago DuSable League is also pressing for its longtime goal: a realistic statue of Du- Sable, perhaps down the river.

Casting such a statue is another matter. Contemporary artists have portrayed him many times — in busts, sketches and even a postage stamp in the 1980's — but historians say they know of no likeness made when DuSable was alive. The stamp portrait was based partly on historical information and renderings supplied by the Postal Service, but only partly. "Just putting two and two together I just came up with what I thought he possibly would look like," said Thomas Blackshear, an artist from Colorado Springs.

In fact, some people are still searching for DuSable's image. Jihad Muhammad and a team of other researchers spent thousands of dollars last year looking in vain for DuSable's remains in St. Charles, Mo. Last week, Mr. Muhammad said that he was raising money to search at two other sites. With the bones, Mr. Muhammad said, he could learn at last what DuSable looked like.

But Linda Wheeler, a spokeswoman for the Chicago DuSable League, said a statue of DuSable required no exact image.

"There are lots of other statues and other structures of people around this city," she said, "and no one knew what they looked like, either."

The long list of panel members advising the city on the park includes Susan Urbas, whose group's purpose differs from some others. As president of the Chicago River Rowing and Paddling Center, Ms. Urbas contends that any fitting tribute will include a community boathouse.

DuSable's history, she said, belongs to everyone. "If you have a theory about where he came from and make it yours, you can," she said. Hers happens to be that he paddled in on a canoe.

Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, National Report, of June 25, 2003.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |