| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted February 25, 2007 |

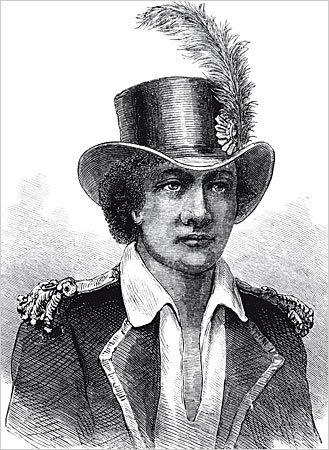

| The Black Napoleon | |

| _________________________ | |

| Madison Smartt Bell tells the life of the Haitian freedom fighter Toussaint Louverture | |

| TOUSSAINT LOUVERTURE | |

| A Biography | |

| By Madison Smartt Bell | |

| Illustrated. 333 pp. | |

| Pantheon Books. $27. | |

| By ADAM HOCHSCHILD |

QUICK, what was the second country in the New World to win full independence from its colonial masters in the Old? Mexico? Brazil? Some place liberated by Bolívar?

|

Bettmann/Corbis |

The answer, Madison Smartt Bell reminds us, is Haiti — which actually gave Bolívar some help.

The years of horrendous warfare that culminated in Haiti’s birth in 1804 is one of the most inspiring and tragic chapters in the story of the Americas. For one thing, it was history’s only successful large-scale slave revolt. The roughly half a million slaves who labored on the plantations of what was then the French territory of St. Domingue had made it the most lucrative colony anywhere in the world. Its rich, well irrigated soil, not yet overworked and eroded, produced more than 30 percent of the world’s sugar, more than half its coffee and a cornucopia of other crops.

When the slaves there rose up in 1791, they sent shock waves throughout the Atlantic world. But the rebels did more than win. In five years of fighting, they also inflicted a humiliating defeat on a large invasion force from Britain, which, at war with France, wanted to seize this profitable territory for itself. And later they did the same to a vast military expedition sent by Napoleon, who vainly tried to recapture the colony and restore slavery. The long years of race-based mass murder (which included a civil war between blacks and gens de couleur, as those of mixed race were known) left more than half the population dead or exiled, and Haiti lives with that legacy of violence still.

Seldom have people anywhere fought so hard for their freedom. Seldom, too, have they so much owed success to one extraordinary man. Toussaint Louverture, a short, wiry coachman skilled in veterinary medicine, had been freed some years before the upheaval. About 50 when the revolt began, he was one of those rare figures — Trotsky is the only other who comes to mind — who in midlife suddenly became a self-taught military genius. He welded the rebel slaves into disciplined units, got French deserters to train them, incorporated revolution-minded whites and gens de couleur into his army and used his legendary horsemanship to rush from one corner of the colony to another, cajoling, threatening, making and breaking alliances with a bewildering array of factions and warlords, and commanding his troops in one brilliant assault, feint or ambush after another. Finally lured into negotiations with one of Napoleon’s generals in 1802, he was captured and swiftly whisked off to France. Deliberately kept alone, cold and underfed deep inside a fortress in the Jura mountains, he died in April 1803.

Toussaint’s is an epic story, and it lies at the heart of a much praised trilogy by Bell, the prolific American novelist. Bell’s new biography, “Toussaint Louverture,” is resolutely nonfiction, however. And welcome it is, for the existing biographies, from Ralph Korngold’s 1944 effort (dated, uncritical and unsourced) to Pierre Pluchon’s 1989 book (quirky, negative and only in French) are mostly unsatisfactory. Bell knows the primary and scholarly literature well, carefully sifts fact from myth and generally maintains a sober and responsible understated tone.

Maybe a little too sober and understated. I can’t help wondering whether Bell, so well known for his novels of Haiti, is bending over backward to show that as a biographer he is not making anything up. I wish he had given more rein to his novelist’s skills — not by inventing things, but by making more narrative use of the wealth of detail there is about this time and place. Part of the problem is that almost none of that detail has to do with the life of Toussaint himself, about whose first 50 years we know next to nothing. Bell points this out, and so the sources he quotes are almost entirely from after Toussaint’s sudden emergence as a leader: his letters and proclamations, and the relatively few eyewitness accounts of him.

But this largely leaves out the rich array of documentary testimony we have about life in brutal, high-living colonial St. Domingue, about people ranging from the planter Jean-Baptiste de Caradeux, who entertained his guests by seeing who could knock an orange off a slave’s head with a pistol shot at 30 paces, to the French prostitute who came to the colony looking for wealthy white clients and then complained to a newspaper that she found too much competition. And both British and French officers left diaries and memoirs about fighting the unexpectedly skilled rebel slaves — accounts as searing and vivid in their frustration as those by American soldiers blogging from Iraq.

Such things are not precisely about Toussaint, but they flesh out the world in which he lived and fought, and American readers unfamiliar with the intricacies of Haitian history need all the help they can get.

Still, this is the best biography of Toussaint yet, in large part because Bell does not shy away from the man’s contradictions. Although a former slave, he had owned slaves himself. Although he led a great slave revolt, he was desperate to trade export crops for defense supplies and so imposed a militarized forced labor system that was slavery in all but name. He was simultaneously a devout Catholic, a Freemason and a secret practitioner of voodoo. And although the monarchs of Europe regarded him with unalloyed horror, he in effect turned himself into one of them by fashioning a constitution making himself his country’s dictator for life, with the right to name his successor.

“Within Haitian culture,” Bell writes, “there are no such contradictions, but simply the actions of different spirits which may possess one’s being under different circumstances and in response to vastly different needs. There is no doubt that from time to time Toussaint Louverture made room in himself for angry, vengeful spirits, as well as the more beneficent” ones. Of such contradictions are great figures made; just think of our own Thomas Jefferson — who, incidentally, ordered money and muskets sent to his fellow slave owners to suppress Toussaint’s drive for freedom, saying of it, “Never was so deep a tragedy presented to the feelings of man.” Adam Hochschild’s most recent book is “Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire’s Slaves.”

Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times Book Review of Sunday, February 25, 2007.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |