| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

More: The Money Issue |

| Posted June 16, 2006 |

|

|

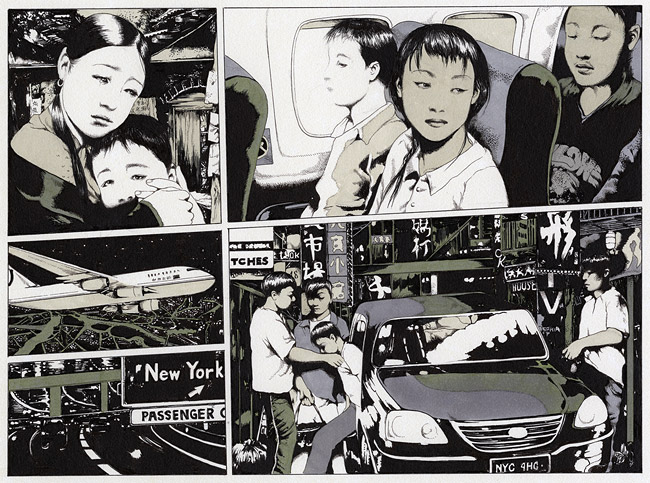

Illustrations By Vania Zouravliov |

THE |

SMUGGLERS' |

| DUE |

| DENG CHEN'S PARENTS SENT HIM TO AMERICA WHEN HE WAS JUST 14 IN THE HOPE OF GIVING HIM A BETTER LIFE. HE SPENT THE NEXT FOUR YEARS PAYING FOR THEIR DECISION. |

|

I WAS INTRODUCED to Deng Chen through an attorney who had helped him with some legal matters. Her specialty is trafficking, and when I told her I was doing some research on human smuggling and its victims, she cautioned me to be careful about using the word "victim" and, more to the point, not to confuse trafficking, which involves coercion, with smuggling, which is by choice. But then she told me about Chen, who at age 14 was sent by his parents to this country from China, by himself, with the assistance of smugglers; over the next four years, Chen worked to pay off a smuggling debt of $45,000, plus interest.

Deng Chen and I first got together this past winter in a room he was renting in Flushing, Queens. The third-floor apartment had been partitioned, so that every room, except the kitchen, was occupied; there were eight people living there, all Chinese, some documented, some not. On a later visit, the holders of the apartment's lease would chastise Chen for bringing a stranger there, but on this occasion no one was around, so we sat on the floor of his spartan room, leaned against his bed and talked for nearly five hours.

There was not much to distract us. On a desk in one corner sat a portable computer, a gift from an older woman who helped him along the way. His rather meager wardrobe fit on three small shelves, on top of which, beside a small bamboo plant, sat framed snapshots of his mother and father, whom he hadn't seen in eight years, and by his television was a bottle of plum wine that he drinks to help him sleep.

Chen, who is now 23, is of slender build. His dress is unobtrusive: on this occasion, he wore jeans, a white collared shirt and Timberland boots. With his soft features, he could pass for a teenager, but his purposefulness is of someone well beyond his years. He is most animated talking about politics; he reads The New York Times online every day and purchases a copy of the Hong Kong-based Sing Tao Daily. His supervisor at the New York Asian Women's Center, where he worked, laughingly told me: "He likes to share his view on society and politics. A lot. A whole lot." Chen can also be restless and fidgety, and often I would notice one of his feet tap-dancing as he spoke, keeping rhythm to the vicissitudes of his journey.

Sometimes during our visits together, it felt as if he would rather be somewhere else, and indeed, on a couple of occasions he would cut our interview short, telling me he needed to be somewhere or meet someone. But periodically he would say something so utterly frank and yet deadpan that it would take me awhile to realize what he was imparting. As we talked on this particular afternoon, he applied tissues to his nose, which was bleeding. He told me that the previous day he had outpatient surgery to repair a damaged septum. It wasn't a big deal, he assured me, though he seemed in some discomfort. I asked him how he was able to pay for the procedure, and he explained that he had health insurance from his job assisting Asian-American women who were victims of domestic abuse. He then volunteered that he had been instructed by the hospital that he needed to have someone pick him up after the surgery. He told me that he had no one to call, and so he paid $20 to an acquaintance, someone he barely knew, to come get him.

As I got to know Chen over the following months, it became apparent that this moment symbolized something larger: his utter loneliness. He once told me that when he had time off from work, he would occasionally stroll to the nearby park, where he would toss a rubber ball against a concrete wall. A solitary figure having a catch with himself. He didn't tell me this to elicit my pity. Rather, he was matter-of-factly explaining what he did with his spare time. It is who he is. Even though others view him as a template for success, Chen sees himself as not belonging, as someone precariously walking the shoreline, an anonymous young man who could easily drift into the currents without anyone taking notice. He told me at one point: "I just don't like people. Unless it's absolutely necessary. I just want to be left alone." But I don't believe it's that simple.

Immigration to America from China has happened in steps. First, the Cantonese came from Guangdong Province, and they were followed by professionals and businesspeople, mostly from Taiwan and Hong Kong. In the 80's, another wave of migrants began, this time from Fujian Province, a mountainous region that sits along the southeast coast of China. The Fujianese being a seafaring people, it seemed only natural that their first means of emigration would be by boat, and in 1993 when the freighter Golden Venture ran aground off the beaches of Queens, their journey became front-page news. What went relatively unnoticed in the coverage afterward is that of the nearly 300 men and women on board the Golden Venture, about 10 of them were under 18, traveling on their own.

In the intervening decade, the smuggling of humans from China has continued, though no one is certain of the numbers; estimates, though elusive, range anywhere from 10,000 to 50,000 a year. Some things have changed. The smugglers — known as "snakeheads" — have become more sophisticated and considerably more expensive. Though many Fujianese still come by freighter or by fishing boat, many now also arrive by plane bearing false papers; moreover, they often land — by boat or plane — first in Canada, the Caribbean or Central America. Immigration and Customs Enforcement reports that in recent months 50 to 100 Chinese each week have been taken into custody trying to cross the Mexican border.

The snakeheads, who in the 1980's had a Mafia-style presence in New York's Chinatown, often publicly beating and kidnapping those who fell behind in their payments, now apply much of their muscle back home in China, threatening and, if it serves their purposes, physically punishing family members of those who have fallen behind in their installments. For those on the Golden Venture, their travels cost roughly $30,000; the snakeheads reportedly now charge upward of $70,000.

As the cost has gone up, the number of years it takes to pay off the debt has risen as well. In the early 1990's, some could repay the smugglers in two years; it now takes twice as long. "A lot of Americans have a hard time understanding it," says Ko-lin Chin, a professor at the School of Criminal Justice at Rutgers University in Newark. "But put yourself in their shoes." If they remain in China, Chin says, they will earn perhaps $200 a month. If they come to the United States, they can earn $2,000 a month working at a restaurant. Once the debt is paid off, most continue to send money home and often help to pay the way for another family member to come to the U.S. Fujianese families with sons or daughters in the U.S. also achieve a certain status. Peter Kwong, a professor of Asian-American studies at Hunter College, has written extensively on human smuggling from China and has visited Fujian. Kwong told me that during his stay in the villages there, residents "would show us that so and so has a two-story house. 'Look at them,' they'd say, 'they have a son in America."' The sobriquet for families with members in the U.S. roughly translates to "relatives of a beautiful country."

Another thing that has changed is that it appears that more children — mostly teenagers — are coming into the U.S. by themselves, without an adult. (This seems to be true of children from other countries too; in 2005, 7,787 unaccompanied minors trying to enter this country were detained by immigration authorities, up 26 percent from the previous year.) For many, their parents have arranged for them to connect with a relative here, but sometimes it is a distant family member who often has no interest in watching after a teenager. They are sent here to work, in the hope that they will be able to send money back home or that they will find a better life. While the numbers aren't necessarily large, they appear to have grown since the early 90's; about six years ago, a former shelter director told me, immigration authorities took into custody several hundred Chinese children coming over the borders and through the airports. (In a one-week period this April, at least seven children from China trying to enter this country were taken into custody by immigration authorities.) These numbers, of course, don't include all those who get in undetected, like Chen. Chen's story is a fairly typical one — except for the outcome. Chen's case, in fact, has pushed some to rethink our definition of human trafficking.

THE DETAILS OF his story were provided to me by Chen, and where I could, I confirmed them with contemporaneous accounts he gave to people along the way or with documentation, including letters he wrote, school records, notes made by staff members during his stay at a runaway shelter and receipts for the money he sent back to China. I also spoke with other young people who had made similar journeys as well as social-service providers who work with those children. Through Chen, his parents, who are in China, declined to talk with me.

Chen grew up in a rural village in Fujian and is the third of three children; he has a brother and sister. He is unsure why his parents were able to have more than one child, though China's enforcement of its family-planning policy has been more vigilantly enforced in some areas than in others. He says that his parents were neither poor nor well off. His father worked at a local food store, which he eventually purchased from the owner, and his mother labored at a brick factory.

He comes from a family that clearly valued education. His brother went to college in Beijing, and Chen's parents sent him to live with a family friend in a nearby town for two years so that he might attend a more prestigious school and, they hoped, follow his brother to the university. Chen says that he narrowly missed qualifying for a top-notch secondary school and so continued his education in his village. His mother frequently talked to Chen of going to the U.S., where she insisted he would have more opportunities and where he could help his family financially. She told Chen that she worried he would end up leading a miserable life if he were to stay in China.

On a fall day in 1997, Chen says, his mother came to his school and told his teacher that something urgent had come up and that she needed to take him out of class. Chen, who was 14 at the time, remembers his instructor, a tall elderly man, arguing with his mother. "He looked at me," Chen recalls. "Maybe he knew what was going to happen." But his mother insisted, and Chen got into a van with his mother and a driver. His mother told him that he was going to the United States and that he would be accompanied by a woman who, it turns out, would pose as his mother. His real mother had packed Chen's clothes in a small suitcase, and she whispered to him that she had sewn $300 in American currency into a pair of his underwear. That was it. No photos. No notes. No mementos of any kind. Just a long, tearful hug at the airport. "Be a good boy," the mother told her son.

| CHEN WORKED 12- TO 13-HOUR DAYS AND WIRED HOME ALMOST HIS FULL PAYCHECK. HE KEPT MANY OF THE REMITTANCE RECEIPTS; THE AMOUNTS AVERAGED $2,000 |

Chen was given false papers for the trip, and at a stopover in Shenyang, he met with a man introduced as "the boss," who alerted Chen to things he might be asked by U.S. customs agents, like the color of American taxis, and then drilled Chen on his new identity. His fiction was that he and his "mother" had returned to China from the U.S. to bury his grandmother and to sell some properties. He never had to answer customs officials, though. Instead, the woman accompanying him did all the talking. They traveled via Seoul, South Korea, where they spent a week holed up in a motel room watching movies, then to Los Angeles and on to New York, where, Chen recalls, they were met by two men, one of whom held his photograph. They quickly hustled Chen and the woman into a car, and they were driven to a basement apartment somewhere in New York.

That same day, he was put on the phone with his mother and was instructed to tell her that he had arrived in New York and that he was O.K. This is typically how the snakeheads work. Chen's family then made their payment of $45,000, money they borrowed from loan sharks, who are usually closely tied to the smugglers. After two or three days, once the payment went through, Chen was released and dropped off on East Broadway in Chinatown, which is the heart of the Fujianese community in New York. He asked passers-by for help in purchasing a phone card and went to call his mother.

DURING ONE OF my visits to Chinatown, I spent time with Steven Wong, who runs the Lin Zexu Foundation of U.S.A., which despite its lofty-sounding title is a shoestring operation run out of a two-room basement office off a short street. Wong is a square-jawed, compact man who at 51 has a small paunch. He smokes Marlboros nonstop, filling the windowless office with a haze, which gives the place a film-noir quality. Wong told me that he first became active in the Fujianese community to fight drugs (Lin Zexu was a 19th-century Chinese official who led a campaign against opium, which ignited the Opium Wars with Britain). Before long, however, human smuggling became a much more lucrative and brutal trade and one that Wong considered a much bigger threat to his community. James Goldman, a former special agent with the Immigration and Naturalization Service who because of his tenacious pursuit of the snakeheads was called "the mongoose," told me that in the mid-1990's the smugglers were so out in the open that everyone knew the address of one of the gangs on East Broadway. The snakeheads regularly extorted money from undocumented workers, on top of the money they already owed. In one case, Goldman and fellow agents discovered a group of young Chinese men chained to an apartment wall where they awaited ransom payments from family members.

Wong has worked as an interpreter for the police and immigration agents (he introduced me to Goldman), but he is probably best described as a fixer, someone to whom people in the Fujianese community come to have their problems corrected. During one afternoon I spent with him, there was a steady flow of people, most of whom brought small offerings of food so that by the end of the day Wong's desk was lined with half-filled cups of tea and half-eaten pastries. A well-dressed middle-aged woman groused to Wong that a dentist had extracted a healthy tooth. Wong promised her that he would call the dentist, though when she left he told me there really wasn't much he could do. (All these conversations were in the Fujianese dialect, so Wong translated.) The weeping sister of a woman who had recently been murdered in Brooklyn pleaded with Wong to help put pressure on the police to solve the crime. Wong assured her that he would try to get the press involved.

Many of the people who come to see Wong — if not most — have complaints about the smugglers. One restaurateur dressed in a black leather jacket accused snakeheads of trying to extort extra money out of his employees. A young fresh-faced woman, her hair pulled back in a ponytail, came in with a document from immigration informing her that she had missed the deadline to get fingerprinted and so was no longer eligible to apply for political asylum. She told Wong that she still owed tens of thousands of dollars to the snakeheads. "If she's repatriated, her entire family will be in a jam," Wong told me later. Wong made a call and quickly calculated there was little he could do for her. "She'll probably go underground," he told me as she left his office. But it was the story told by the first person I met that stayed with me the most. He was a stoop-shouldered man in his 40's with a weathered face. I had walked in at the end of the conversation, and Wong was clearly giving instructions, to which the man nodded in agreement. When he left, I asked what that was about. Wong told me that the man's brother had come over from Fujian six months earlier and had quickly fallen behind in his debt. As a result, the snakeheads had exacted revenge, brutally assaulting the brother's wife and 12-year-old son, both of whom were still in China. Wong had been pleading with the man to have his brother come see him.

MANY FUJIANESE BORROW THE SMUGGLING FEE FROM FAMILY AND FRIENDS, BUT OTHERS, LIKE CHEN'S FAMILY, RELY ON LOAN SHARES, WHO CAN AND WILL EXACT REVENGE IF DEBTORS FALL BEHIND. |

When Wong first learned of the assault, he had a friend in China videotape the two in the hospital, as well as the home where they had been attacked. After the brother-in-law left his office, Wong offered to show me the tape. It begins with a closeup of the sister-in-law, her head completely shaved, the hospital sheets bloodied. She has three long slash marks across her face and one along her neck, as if the assailant, who apparently attacked with a meat cleaver, was aiming to decapitate her. She appears to be unconscious. The boy has two long, crisscrossing slash marks on the back of his shaved head; Wong speculated that the assailant slashed at him as he tried to flee. The video of the home is no less gruesome. The intruder used a ladder to enter the second floor flat, where the floor, the wall and even the ceiling are splattered with blood. "Coldblooded," Wong said.

Goldman, the former I.N.S. agent, told me that the strategy of the snakeheads has been rather simple: "You have to pay, and if you don't pay, there will be a problem."

In that conversation with his mother in October 1997, Chen learned of the debt his family now carried. His mother, he recalled, cried, telling him that he had to send money home or their lives would be in danger. It was a message she delivered to Chen repeatedly over the next four years. Many Fujianese borrow the smuggling fee from family and friends, some of whom have already carved out a life in the U.S. But others, like Chen's family, rely on loan sharks, who can and will exact revenge if debtors fall behind.

Chen told his mother that he didn't know where to go. She instructed him to ask around for the employment agencies, and as soon as he hung up, he found his way to Eldridge Street, lugging his suitcase behind him. The sidewalks are crowded here nowadays, mostly with young men smoking cigarettes, sitting on the stoops and chatting on cellphones, waiting to catch one of a half-dozen or so buses lined up across the street; the buses advertise their destinations: Hartford, Allentown/Bethlehem, Northampton. When the distance grows, the destination becomes less specific: Ohio, Michigan, Maryland, Tennessee. The employment agencies are cramped single-room storefronts; the employees work behind a sheet of Plexiglas that is covered with scraps of paper organized by area codes and giving the positions available and the wages offered. For $30 or $40, the agency will connect job seekers with one of these positions, most of which are at Chinese restaurants run by Fujianese.

In one three-story building alone, there are five agencies, two on the first floor and three on the second. It was here where Chen says he first went; he was barely able to see over the counters and was told that he was too young. According to medical records at the time, he was 5-foot-3 and weighed 100 pounds. He was a wisp of a boy.

He then trudged to Seward Park, where he spent the next three nights sleeping on a bench, one hand resting on his suitcase to make sure no one took it and his head resting on a rolled-up jacket. Chen returned to the employment agencies only to be turned away again. Dejected, he plopped onto the black metal steps on the second landing, his head in his hand. A middle-aged man approached. Chen was surprised when the man asked about his father. The man was from Chen's village and had recognized him. He offered to let Chen sleep on the floor of the room he rented and found him a job at a local garment factory cutting loose threads from shirts. Chen earned about two cents for each piece of clothing he trimmed and later found a bed in an apartment with eight other, mostly undocumented, Fujianese. The women at the factory, upon hearing Chen's story, would speak scornfully of his mother, calling her "coldhearted." How could she send him over here on his own? Chen soon became angry himself.

Chen was determined to continue his education, and so he persuaded an older man at the factory to act as his guardian. Three months into his stay, on Jan. 9, 1998, according to school records, he enrolled at P.S. 56, the local junior high school. Chen says that he would often nod off in class, exhausted from the late nights cutting threads and then returning to an apartment where the men, who worked in the restaurants, stayed up late playing mah-jongg and listening to music.

Chen became downcast and contemplated taking his own life, but he remembered a story that circulated in his village about an entire family who had been murdered because the son in America got considerably behind in his payments to the smugglers. And in his regular phone conversations with his mother, she would often burst into tears, relating to Chen the threats from the loan sharks because he wasn't sending enough money; she urged him to quit school so he could earn more. Chen sent most of his pay home, and remembers one week having to scrounge for change in his apartment to buy a dozen eggs and rice, which he subsisted on for a week.

Chen needed to make more than the $400 to $500 a month he was earning at the garment factory, so he persuaded one of the employment agencies to send him to a job at a Chinese buffet restaurant in Wildwood, N.J., where he could make $800 monthly. He dropped out of school (after just a few months) and stayed in Wildwood for nearly a year, longer than he remained at any other restaurant. His first job was as dishwasher, but because of his small stature, he needed a crate to stand on. It was, he says, the worst of a long list of places he worked.

There was nothing dramatic about this time, but rather a slow, grinding-away of the senses, of the soul, like dripping water that erodes the contours of a mountain. He was just a boy — the other workers called him "little brother" — who knew that if he didn't send money home, his parents might be assaulted or, worse yet, killed. That is what he lived for — or rather against: to avoid such a calamity. So he worked 12- to-13-hour days with one day off each week. At each restaurant, the owner housed the employees, most of whom were undocumented, in crowded apartments, often five or six to a room. Since meals were also provided, Chen was able to wire home almost his full paycheck. He kept many of the remittance receipts; the first is for $800, but they soon reflect his new earnings with amounts averaging $2,000. He traveled as far as Augusta, Ga., and Franklin, Va., and worked in some places, like Poughkeepsie, N.Y., more than once. Sometimes, Chen told me, he would last only a week or even a day at a new job. Maybe it didn't pay as advertised. Or the owner just needed him to fill in for someone who was ill. Or Chen would try to pass himself off as a cook, since they made more money, and his ruse would quickly be discovered. One time, in Columbus, Ohio, the owner came to pick him up at the bus station, took a look at him and drove away. Chen called to plead with him and was told, No, you're too young. He remembers one restaurant owner who retrieved him at the bus station and then made a short stop at a brothel, where the young Chen waited for his new boss amid Asian girls in lingerie. "Oh, it smelled so good," he told me, laughing.

The loneliness was the worst, he said, on the long bus rides. It was there that all his worries would accumulate and that he would try to make sense of his parents' decision to send him here. "I hated them," he said. "I felt like my mom only cared about money, that she cared more about money than me." He would speak to his mother regularly and assure her that everything was O.K. He didn't want her to worry. "After a while, we didn't have much to talk about," he said. "I told her my life had improved." Soon their once-lengthy conversations became short updates, rarely lasting more than five minutes.

Chen realized that one of the best restaurant jobs was taking orders over the phone, so he taught himself rudimentary English with a paperback book called "Practical English for Chinese Restaurants." He practiced with the boss's daughter in a town in West Virginia: she took a liking to Chen, and on one of his days off, they went on a date to McDonald's. Toward the end, Chen made as much as $2,900 a month as a manager. For Chen, the three and a half years he spent in the restaurants run together. Technically, he could have quit at any point along the way, but he knew the repercussions for his family. "It's slavery because the children don't have a choice," says Susan Krehbiel, director of children's services for the Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service. They are pressured, Krehbiel adds, "by both fear and a sense of honor. They're caught up in a transnational network that is so beyond their understanding, and they're clearly just a small piece in a much larger drama that they have no control of." In the mid-90's, Krehbiel's agency put a moratorium on placing Chinese children in foster care because the snakeheads tracked down the foster parents in an effort to get the children back to work.

| DOROTHY HAMILL |

| RICH Winner of an Olympic gold medal in figure skating in 1976 at age 19. "Money is very evil," she says two years later. Owner of the Ice Capades for two years, she sold it to Pat Robertson. POOR Declares bankruptcy in 1996. |

At the Door, a refuge for wayward teenagers in New York City, the staff has in the last few years seen an increasing number of teenagers from China who, like Chen, came to the U.S. on their own. Hsin-Ping Wang, a Door counselor, says that some have come in because of suicidal thoughts or because they are completely lost and have nowhere to turn. Most, she told me, are under such pressure because of the debt that they have completely withdrawn; they remind her of austistic kids. One 17-year-old boy came to see her and said nothing other than that he had come to the U.S. with his older sister. Wang tried to coax his story out of him, but he remained silent, and after the session, he told Wang that he felt better. She has had others who have spent the time crying. "I think sometimes they just need someone to witness what's happened to them," she said. Most, she told me, come to see her once and then never return, mostly because of their frenzied work schedule but also because in the end there is little she can do for them. They have a financial bargain to maintain, and they know the consequences if they don't.

If there is any way to measure the impact of these years on Chen, it is in taking a look at what happened immediately afterward, once his debt was paid off. "You didn't have much time to think" while working in the restaurants, Chen told me. The experience didn't fully sink in until it was behind him.

In January 2001, he returned to New York and enrolled himself at Liberty High School, where he performed well, achieving an 85 average. During that year, he continued to work, in a restaurant in Manhattan, to pay off the remainder of his debt. (By the summer, he had roughly $6,000 remaining, and so he traveled again, to work in West Virginia.) A teacher with whom Chen had shared his story arranged to have Chen move to Buffalo in January 2002; there, an immigration attorney offered to assist him in obtaining legal status. Chen lived in constant fear that he would be deported to China, where he might face imprisonment for leaving the country illegally and where he would bring shame to his family.

There is some dispute about what happens to those who are repatriated to China, in part because there have been so few. Last year, 540 Chinese were returned; 39,000 Chinese in the United States are currently under orders of removal, however, and the U.S. government is now trying to get the Chinese government to issue them travel documents. A Department of Homeland Security spokesman told me, "We have no reports of people who have been sent back to China being persecuted." Others, though, are not so sanguine. Two years ago, Richard Posner, a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, vacated a deportation order for a Chinese youth because the immigration judge did not consider the evidence — numerous human rights reports from both U.S. and British organizations — that the asylum seeker might well be sent to jail or a labor camp if returned to China. Posner was concerned that the Chinese youth might be tortured upon his return, though he also conceded that "the treatment of repatriated Chinese by their government is to a considerable extent a mystery." Indeed, one Chinese legal scholar I spoke with, Daniel Yu, said that while there is a law on the books in China that calls for a short jail sentence if a person leaves the country illegally, more than likely whatever punishment there might be is at the discretion of local officials.

In Buffalo, Chen unknowingly wandered into the protective arms of four women: a congressman's wife, a high-school teacher, a counselor at a runaway shelter for young men and an immigration attorney. Each saw the same drive and melancholy in Chen and so reached out to help him. The congressman's wife, Pat LaFalce, became the closest. She met Chen in his early days in Buffalo when he briefly stayed at a refugee center where she volunteered. "He was always on edge," she told me. "He always reminded me of a jack-in-the-box because he couldn't sit still." At a college basketball game to which LaFalce had taken Chen, he first opened up to her about his journey, and he shared with her that he didn't understand why his parents sent him away and on his own. "Why, why, why?" he would sing. "My maternal instincts kicked in," she told me, and from that point on, LaFalce did what she could to help Chen gain his footing.

LaFalce took Chen on outings, got him glasses and enrolled him in Grover Cleveland High School. At the school, Mary Claire Kosek, who taught English as a second language, remembers him as being resolute about life. "He worked so hard," she recalls. "He was unstoppable." Chen entered midway through the school year and insisted on catching up on the work he had missed. "Sometimes," she said, "he would just put his head down, and I'd ask him what's wrong? He wouldn't say anything. You could just see it in his eyes. Sometimes he was just so sad. I mean so sad."

Chen found more permanent lodging at the Franciscan Center, a shelter for runaways, where he would live for a little more than a year. In the early months, the staff worried about him. He seemed unable to relax and kept to himself. The other boys interpreted Chen's distance as snobbery; Chen would sometimes chastise them for watching television and not studying, and he rarely joined them at the movies or in the park. They would confront him: Why did he think he was better than them? they would ask. But it was his inability to slow down and his low spirits that most concerned Maureen Armstrong, a case manager who is now the home's assistant director. A few weeks into Chen's stay, at 9:30 one night, Armstrong received a call at home from a staff member on duty. Chen, she was told, had unraveled. Armstrong rushed to the shelter and found Chen curled up in a fetal position on the floor of his room by his dresser. He was wailing like a wounded animal. The other boys were standing in the hallway, frozen, trying to assure Chen that it would be O.K. She could hear him, through the sobs, telling the others they were wrong, that it wasn't going to be all right. Armstrong got on the floor and held Chen, rocking him, urging him to take slow, deep breaths. "I've been a good son — I've been a good son," Chen sputtered, his nose running, his chest heaving. "Why did they do this to me? I hate them for making me be alone. My family, why'd they turn their back to me?" It took Armstrong well past midnight to calm him.

The experience unnerved Armstrong. "I've been doing this for 30 years," she said, "and I can tell you what I saw that night shook me to my core. The only thing I could tell him was that his parents meant well, and somewhere down the road it'll make sense. Your parents will explain it someday."

After that, if Chen had a particularly hard day, usually because he was stressed about his efforts to obtain legal status, Armstrong would have him sleep on the couch in the downstairs living room so that a staff member could keep an eye on him. The other boys, too, now felt that they understood Chen better, and they set aside a room in the house where he could do his homework. On weeknights they often agreed to do his chores so he could study. He would do their chores on the weekends in return. What most weighed on Chen was his future, whether he might be returned to China. Anne Doebler, who at the time was an attorney at the International Institute of Buffalo, which provides services to refugees and new immigrants, at first didn't know what to do with Chen's case or if he even had one. Political asylum didn't appear to be an option, since he couldn't make the claim that he had been persecuted in China. Another consideration was Special Immigrant Juvenile status, which applies to children who enter the country by themselves and who can't return to their families, usually because of abuse or abandonment. But you need to be under 18, and Chen was about to celebrate his 19th birthday. Doebler considered telling Chen to disappear, to go underground; she feared that alerting the authorities to his existence would get him deported.

The final option was a T-Visa, which was so new it was untested; it was meant for victims of trafficking. During the 1990's, Congress became alarmed at the large numbers of women from the old Soviet bloc who were being brought into this country as prostitutes, usually against their will, and so Congress passed the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000, which included relief for those who had been subjected to sexual or labor exploitation.

Doebler thought she could make a strong argument that Chen, because of his youth, had not come here of his volition and that once here was in debt bondage, forced to work because of the threats to his family. What undoubtedly helped Chen's case is that he held on to many of the receipts for the money sent back to his family and that he held on to his immunization forms when he was briefly enrolled in junior high school in Chinatown. It was evidence that he entered this country at age 14. Since Chen's case, I've learned of two other Fujianese émigrés, both girls, both sent to this country under similar circumstances, who have received T-Visas. (Only 652 T-Visas have been issued.) Suzanne Tomatore, the lawyer for one of those girls, told me that until she met Chen, who had come to her for assistance renewing his work permit, and heard his story, she would have considered his situation smuggling. "It's one of those things where you know something wrong happened," said Tomatore, who is the director of the Immigrant Women and Children Project at the New York City Bar Association. "The biggest factor is that a child doesn't have the capacity to make that decision" to emigrate. Tomatore said that, in fact, before she met Chen, a youngster who had a similar story approached her for help, and she went back and forth about how best to assist him. In the end, he was too terrified of the snakeheads — he was still paying off his debt — to fully cooperate and eventually drifted away. With his T-Visa, Chen would be eligible to become a permanent resident, the first step toward citizenship.

Chen graduated seventh in his class at Grover Cleveland and won a couple of small scholarships to attend the University at Buffalo, where he completed his freshman year. Then, suddenly, he decided to return to New York City. He says it was in part because he missed being around other Chinese, but he had some Chinese friends in Buffalo, including for a while a Chinese girlfriend. I once asked him why he felt compelled to keep moving. "It's just life," he said. "You have to survive."

Pat LaFalce remembers getting a call from Chen, asking if she could pick him up at a restaurant where he was working part time. When she got there, he had a suitcase, and she realized this was it, he was on the go again. Chen asked her to drop him off at the house of a friend, and so she did, leaving him on the stoop of his friend's house, where he sat to wait for his ride to the bus terminal. For a moment, LaFalce sat in the car looking at Chen. "His expression turned very dark," she remembers. "His eyes were darting back and forth, back and forth. Just for a minute I thought about getting out of the car and telling him he was a wonderful example, but I thought, It's just going to make him very uncomfortable. I knew I might not see him again. So I just kind of waved, and he kind of waved back." Chen talks of LaFalce, who, when he entered college, gave him the computer I saw in his room, as one of the most important people in his life, but with the exception of a couple of phone calls and e-mail messages, he has not been in touch. Chen has learned not to look back.

DURING MY LAST visit with Chen, we walked to the park where he would occasionally come to have a catch with himself. We sat on a bench, the late-afternoon March sun warming us. Chen seemed preoccupied. At one point, he rested his head on the bench's cement support, his eyes closed, his mind elsewhere. He told me that he was trying to arrange to have his parents come to the U.S., which as a trafficking victim he is permitted to do. He wasn't sure if they would choose to stay or just visit, but he was clearly looking forward to seeing them again. In our conversations, he told me he had come to forgive them. He had come to understand their actions this way: they had honored him by sending him to the U.S.; they had put their trust in him. What if, he said, he had come here and didn't work? What if he was lazy? What if he joined the gangs? They thought enough of him, he told me, to send him on his own, knowing that it was on his shoulders to earn enough money to repay the smugglers' debt. "They trusted me," he said. It seemed only natural that a child would look for ways to explain that which didn't make sense, especially when it comes to the people he loves most.

But it wasn't this revelation that most surprised me that afternoon. Rather, it was the news that he had left his job at the New York Asian Women's Center, where he had been for nearly a year and where his supervisor had told me she treasured his uncanny ability to connect with the clients. "It was too depressing," Chen told me. One incident in particular had unsettled him. The teenage son of a woman staying at the center's shelter had been acting out, and Chen was appointed to ask him to leave. The boy was apparently depressed and angry, and Chen talked with him one on one in their Fujianese dialect; a co-worker of Chen's remembers the boy bursting into tears. Chen saw himself in that boy, and he told me that he did all he could to keep from crying himself. He also said that the job didn't pay enough and that he needed to earn money to pay his parents' way here. It was then that he mentioned that he planned to return to restaurant work. He figured he could make good money there since his expenses would be kept to a minimum.

Chen, I had come to learn, can be hard on himself. Once, walking through his neighborhood in Flushing, he told me: "I feel like I'm in between, that I'm stuck in the middle. I don't feel like I'm like a peasant who came to the United States to work in the restaurants. And I don't feel like one of those people who are really smart and can interact with regular Americans. The reality is, I started late. I have too many problems that distract me. My loneliness. I don't have a support network. That's the main problem, I feel lonely."

Trying to boost his spirits, I said, "You've had a remarkable life." To which Chen replied: "I prefer not to have it. I wish I was still a child. I wouldn't have to think very much."

The last time I spoke with Chen, he wasin Pennsylvania working at a restaurant. While we were on the phone, he asked me if I could go on the Internet to find the phone number for the admissions office at Stony Brook University. He told me that he wanted to inquire about financial aid. A week back on the restaurant circuit, and Chen was thinking about his next move.

Alex Kotlowitz is a regular contributor to the magazine. His last article was about a Kurdish immigrant fighting deportation.

Copyright 2006 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times Magazine of Sunday, June 11, 2006.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |