| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted August 30, 2009 |

| Books |

|

The Price of Colonialism |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

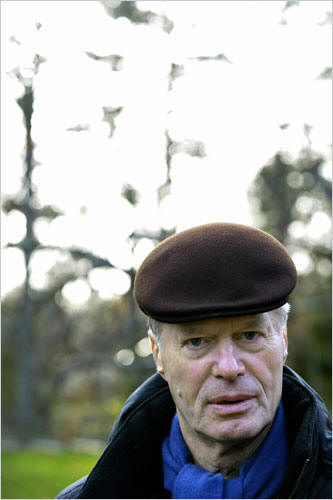

HENRIKSSON/AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE/GETTY IMAGES |

|

| J.M. G. Le Clézio |

|

By ELIZABETH HAWES |

| ____________________ |

| DESERT |

| By J.M.G. Le Clézio |

| Translated by C. Dickson |

| 352 pp. Verba Mundi/David |

| R. Godine. $25.95. |

| ____________________ |

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |