| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted November 12, 2006 |

The Marxist Turned Caudillo: A Family Story |

|

|

|

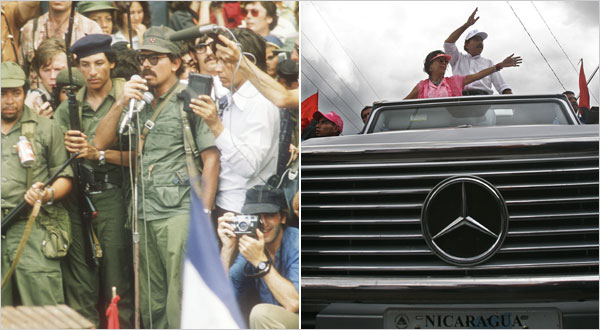

From left to right Matthew Naythons/Liaison, via Getty Images; Esteben Felix/Associated Press |

|

| Then and Now The rebel of 1979 (left) and the candidate (with wife) last month. |

By STEPHEN KINZER |

AFTER seizing power in Nicaragua in 1979, Sandinista revolutionaries helped themselves to the riches their defeated enemies had left behind. One “comandante,” Daniel Ortega, cast his eyes upon a walled mansion in the center of Managua that was owned by a banker who had fled to Mexico. Without even the pretense of legal procedure, he confiscated the house and moved in. The owner, Jaime Morales, joined the counterrevolutionaries — the contras — and vowed to destroy the new regime by military force.

Despite hundreds of millions of dollars in American aid, the contra war failed. But so, in the end, did the Sandinistas. In 1990, Nicaraguan voters rejected Mr. Ortega. After a period of seclusion, he re-emerged with a new identity — the old-style “caudillo” who uses ideology when it suits him but is dedicated mainly to the pursuit of power.

Last week, Mr. Ortega’s transformation was crowned with triumph when, on his third try, he won the Nicaraguan presidency in a free election.

His vice president is none other than Mr. Morales, who moved back to Nicaragua after the civil war ended, reached a “private arrangement” with his old nemesis (reportedly involving a land swap), and gave up his claim to his old house.

During the 1980s, Mr. Ortega denounced the contras as “beasts” and vowed to fight them unto death. No one in Nicaragua, however, was surprised when he chose a former contra as his running mate.

Mr. Ortega is, after all, a crusader for good government who has allied himself with the country’s most corrupt figures; an advocate of the poor who has become very rich through a series of mysterious business deals; and a leftist ideologue who has proven ready to embrace any cause — most recently a total ban on abortion — that will bring him political advantage.

Nicaragua is a small country of 5.6 million people. Every member of the political class knows every other member, and in many cases they have complex personal and familial ties. To outsiders, the country seems bitterly divided by politics. Political disputes, however, often mask feuds within families and clans. Outsiders may interpret Mr. Ortega’s abandonment of nearly everything he once seemed to believe as an act of spectacular cynicism. To Nicaraguans, it is just the latest example of how leaders of their quarrelsome nation are, in the end, prone to forgive each other and find new ways to share the spoils.

That is not the only aspect of Nicaraguan political life that has remained constant despite the huge changes that have reshaped the country over the last quarter-century. Nicaraguans, like people in some other Latin American lands, are still ready to support populist leaders who rule through the force of personality rather than through institutions. They remain suspicious of the United States, which has repeatedly intervened in Nicaragua over the last century. And they are as fascinated as ever with family melodramas that play out on a national stage.

| Sandinistas. Conreas. Clans. They quarrel, make up and share the spoils. |

For much of Nicaraguan history, the spiciest of these dramas involved the Chamorro and Somoza clans. Now the Ortegas have joined the show.

The president-elect’s brother, Humberto, who was the Sandinista defense minister in the 1980s and who has since made a fortune in business, refused to endorse his brother’s candidacy. Daniel Ortega’s stepdaughter has accused him of sexually abusing her starting when she was 11 years old and he was 34. His wife, Rosario Murillo, remains unswervingly loyal. She ran this year’s political campaign, in which her husband granted no interviews and participated in no debates, and she is expected to play a key role in his government. Some are already comparing her to Dinorah Sampson, who during the 1970s was the mistress of President Anastasio Somoza Debayle and a sinister power behind his throne.

“In the 1980s, Ortega ruled as part of a collective Sandinista leadership,” said Carlos Fernando Chamorro, who was editor then of the official Sandinista newspaper while his mother, brother and sister ran the embattled opposition paper. “Now it’s much more about personal and family power. That’s new for Ortega, but for Nicaragua it’s an old pattern.”

Some officials in Washington seem ready to confront Mr. Ortega again. They warn that he is about to become the Central American surrogate for President Hugo Chávez of Venezuela, the newest figure on Washington’s enemies list. Yet many Nicaraguans, including some former contras, want the Americans to give Mr. Ortega a second chance.

“When the Sandinistas came to power, they came in dirty uniforms, with no experience other than giving orders,” said Adolfo Calero, who during the 1980s headed the largest contra faction. “They were barbarians at the banquet. Now they’re older. They have families, and many of them have very strong economic interests. I expect a totally different attitude. My hope is that power won’t seduce them, as it did last time, but make them more responsible.”

In his years out of office, Mr. Ortega became a master of backroom compromise. Soon after beginning his recent campaign, he signed a statement promising to support private enterprise and the Central American Free Trade Agreement. In the coming weeks, he is expected to ask business leaders to recommend candidates for top posts.

But as Mr. Ortega won over former enemies in Nicaragua, many old allies, including most of the comandantes with whom he ruled in the 1980s, broke with him because they could not abide his egocentric style and undisguised lust for power.

“Over the long run, he is going to want to consolidate his power in ways that would go beyond one presidential term,” predicted one of these defectors, Sergio Ramírez, a novelist who was Mr. Ortega’s vice president during the 1980s. “His basic impulse is authoritarian, and his friendships with Chávez and Fidel Castro reinforce that.”

Copyright 2006 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Week in Review, of Sunday, November 12, 2006.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |