| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

More Special Reports |

| Posted July 25, 2006 |

|

|

|

|

| Difficult Call | |

| When is a mother so troubled, or troubling, that a walfare worker must take her kids from her? By DanielBergner |

TO make the letter look right, Marie needed a computer, so one day in March she walked to a public library. There she composed at the keyboard, but the writing didn’t go well. She had the first of her five children at 13, spent part of her teenage years in a group home and part in the home of her crack-addicted mother and never reached high school. “You know,” she told me later, “the way I sound sometimes doesn’t sound like it’s supposed to.” But she wasn’t leaving that library without the letter she needed. College students were studying nearby, and Marie, who is 29, interrupted one of the girls. To this stranger, she confided her situation. And soon, with the girl’s help, she began again.

“To whom it may concern,” she typed, “I am writing to you to appeal for the return of my children.” Marie (I am using her middle name, as well as the middle names of her children, to protect their privacy) lost her kids, all of them boys, to the State of Connecticut more than a year ago. The Stamford office of Connecticut’s Department of Children and Families has placed the boys in an array of shelters and foster homes; it has recently found potential adoptive parents for four of them; and earlier this month it filed a petition to end Marie’s role and rights as a mother. If the department, known as D.C.F., succeeds in court, she will lose her children forever.

For the time being, Marie is still entitled to spend about one hour each week with her sons. I first met her in early April, in a visiting room at the Stamford D.C.F. office. A cloth wall-hanging of panda bears in a classroom adorned one scuffed wall, and crayon scribbles covered another. Christopher, who is 3 and Marie’s second-youngest, was sick that day and had stayed at his foster home, and Joseph, at 16 Marie’s oldest, had fled during an outing with the family’s D.C.F. social worker, Annette Johnson, the previous October and was nowhere to be found. So just three of the boys gathered around Marie, who is Puerto Rican-American and wore her long fingernails painted pink, her dark hair pulled into a ponytail with a powder blue tie, a gold nose stud, several tattoos, blue jeans and tan work boots. Between the ponytail and her short, square build, she looked half cheerleader and half fullback. She managed her cranky blond year-and-a-half-old baby, Diomedes, in her lap, and played a game called Jumpin’ Monkeys with Antonio and Anthony, who are 8 and 6 and shot plastic monkeys from a spring-loaded launcher, trying to hook them in the branches of a little tree. In her low, raspy voice she gave them advice when they missed (“Papi, you got to hit it soft”) and congratulated them when they scored (“You got a banana!”).

For child-welfare |

|||||

| social workers like | |||||

Annette Johnson, |

|||||

there is no more |

|||||

| wrenching decision | |||||

than whether to reunite |

|||||

| children with their | |||||

troubled mother - or |

|||||

| to sever those ties | |||||

forever. |

|||||

|

|||||

By Daniel Bergner |

|||||

|

|||||

Photographs by Joachim Ladefoged |

|

“Give me a kiss,” she said, and Anthony, who has black bangs, dark almond-shaped eyes and delicately curved lips that sometimes spread into a beaming smile, did. “Let me try for Mommy,” he demanded, and climbed into Marie’s lap alongside Diomedes. He launched a monkey for his mother.

“Can I use the bathroom?” Antonio asked.

“Don’t touch the toilet seat,” Marie warned.

“Could you read us a book before we go?” Anthony begged, time running out. “Please, now?”

Marie took a book from a table and began steadily: “Simba and Nala at play.”

Her steadiness lasted through goodbye. But when Johnson loaded the boys into a blue D.C.F. van to be delivered back to their foster parents, and when the van turned out of the parking lot and disappeared, Marie started to tremble. “They’re going T.P.R.,” she said, referring to the department’s plan to file for termination of parental rights. “I did everything they asked me. I’m trying to believe this is what God wants, but I can’t believe this.” She said that at birth, Christopher had tested positive for marijuana, that Diomedes had been born positive for marijuana and cocaine. “I fell in the game. I messed up, I know I messed up, but all I did was the drug use. I addressed everything. I’ve been clean for a year. I went inpatient. I have the paperwork. My kids are going to be taken from me for good.”

I asked if I could accompany her home. It was a chance to see her house the way the D.C.F. social workers often see the homes of their clients, showing up with no appointment, no warning, allowing no time for the clients to prepare, to clean, to hide the depths of their lives’ disarray. I was ready for dilapidation outside, decay within. We took a taxi through Stamford, a city of about 120,000 with glass-sheathed corporate headquarters, beachfront mansions and crouched, decrepit houses fronted by rusty fences. A bright white picket fence surrounded Marie’s small home, on a modest, resilient block. The pale yellow clapboard facade looked freshly painted, and inside the wood floors gleamed. So did every surface in the kitchen, except the refrigerator, which was covered with fruit-shaped magnets — pears, strawberries — and pictures of the children. I asked how long she had lived here, wondering if she had just moved in, if there hadn’t been time for the place to become run-down.

“Three years,” she said. Disability payments for epilepsy and money from the family of Diomedes’s father helped pay the rent. She showed me the spotless highchair that awaited Diomedes’s return, and in the tiny bedrooms downstairs, the children’s beds and toy box and shelves of precisely aligned kids’ DVD’s, all looking like a display in a furniture store. At the kitchen table, she laid out letters and drug-test results from the state-supported treatment programs she had attended, all proving that for the past year, since a few months after Diomedes’s birth in December 2004, she had stayed drug free. One program noted Marie’s “motivation and commitment to her recovery.” Another wrote that she “has been a pleasure to work with” and “appears to be doing everything that she can to get her kids back home with her.”

Marie knew that the department doubted not only that she had enough strength to stay clear of drugs but also that she was fully committed to the boys and that she had enough skills to successfully mother them — especially Antonio, who has attention deficit and hyperactive disorder. She showed me more of her library work: a three-page printout from the Web called “The Gift of A.D.H.D.” Alongside her drug-test results she set a gold-trimmed graduation certificate from a state-financed “nurturing/parenting” class, where, a letter from the program described, she had been taught “positive parenting technique” over a minimum of seven two-hour sessions.

'I did everything they asked me,' Marie said, and acknowledged: 'I fell in the game. I messed up, I know I messed up, but all I did was the drug use, I addressed everything. I've been clean for a year. I went inpatient. I have the paperwork. My kids are going to be taken from me for good.' |

The next week, at a special outdoor visit with her kids in the park across from the D.C.F. office, Marie arrived with a pink plastic serving bowl full of homemade chicken, yellow rice and peas. She doled out the picnic lunch in red and blue bowls and plucked a small bone from a piece of chicken so Christopher wouldn’t choke. After they ate, Antonio and Anthony played with a Wiffle Ball and bat she had bought for the occasion, and after the visit, the social worker who had quietly supervised it, Beverly Maybury, who was not the family’s regular worker but had spent 17 years with the child-welfare systems of New York and Connecticut, said, “People are complicated.” Maybury is an African-American woman with a nose stud much like Marie’s, gold streaks in her hair and a taste for beaded-and-embroidered jeans. “Maybe some of these people at D.C.F., they think it’s cut-and-dried, but people who’ve seen some of the spice of life, been through some things, they know it’s not that way. Those kids are bonded. Maybe someone’s going to say she’s not parenting, but look at that food, that looked pretty parenting to me. We can’t just throw people away. She’s clean. She’s showing up for her visits. She’s playing with them. You’ve seen that house, it’s spick-and-span.”

During the visit, Anthony noticed something different about Marie in her midriff-baring T-shirt. “Mommy,” he asked as she gathered up the bowls, “you got another baby in your belly?”

She did, and soon learning this, the department decided it would petition the court while the baby was still in the womb. Based on “predictive neglect,” it planned to claim her sixth child, permanently, the instant it was born.

Pictures of Marie's children decorate Annette Johnson’s cubicle. Perched atop one of the cubicle’s partitions, above the piles of case reports on her desk, is a Peter Pan Happy Meal pirate ship, a gift from Antonio on a day Johnson treated him to a McDonald’s lunch. A miniature Ninja Turtle, a present from Anthony, sits nearby, beside a figurine of a girl playing the fiddle, an offering from another child Johnson watched over for a time.

Around her, the 30 or so staff cubicles and eight supervisors’ offices form a Stamford D.C.F. headquarters that looks nothing like it did when Ken Mysogland, D.C.F.’s Stamford-area director, started out as a social worker 17 years ago. Back then, he recalls, the electricity was sketchy, the lighting bleak, the phones unreliable. Workers shared broken desks as each strained to deal with caseloads of 50 or 60 at a time. Spurred by a 1989 lawsuit and 1991 federal court consent decree, the department has gradually transformed itself. Its budget has tripled in the last decade, and it appears close to working itself free of court-imposed goals and monitoring. At the Stamford office, all is bright, all is functional; the staff members are each responsible for 15 to 20 cases, and though the work can be frantic, the social workers seem to have at least a bit of time to weigh decisions about the families they investigate and oversee.

Most of these families live in hard-pressed sections of the city and its surrounding towns, in a part of the state that lies beside Long Island Sound and is celebrated as “the gold coast.”

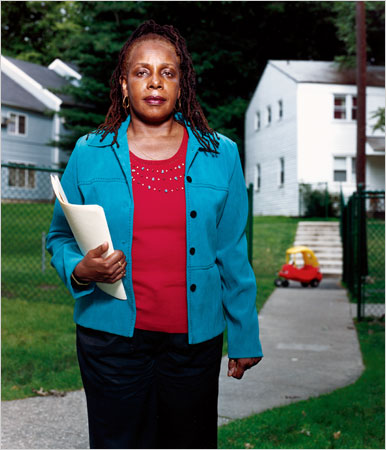

When Johnson, who is black and in her mid-40’s, first came to the department two and a half years ago, she desperately hoped that she would never take a child from its family forever. For the child, she explained, her thickly braided hair falling in a spirited way over the collar of a pinstriped suit, the complete and final failure of a parent can be more traumatic than a parent’s death. Skip to next paragraph Readers’ Opinions Forum: Parenting Where should social services draw the line on taking children away from their parents?

Before following her mother into social work in the early 1990’s, Johnson was a marketer for Procter & Gamble, making sure that the company’s cleaning products were well placed on store shelves. Yet she had, in fact, seen plenty of what Maybury called “the spice of life,” and not only while doing social work with the homeless, substance abusers and mentally ill before joining D.C.F. Her younger brother had been a drug trafficker’s mule: he swallowed a cocaine-filled condom, the rubber tore open inside him and he died of the overdose. Six of her cousins died because of addictions to heroin: from overdoses, from AIDS.

Johnson’s age and master’s degree in social work make her an exception among her Stamford colleagues; even her brief time in child welfare makes her “senior staff,” she said, joking. Across the room, a 24-year-old with a year’s experience was getting ready to seize a newborn, whose enraged mother had tested positive for PCP when she checked into the hospital to deliver. “You want me to get a car seat?” a colleague called out, helping the 24-year-old get ready. Child seats lie on file cabinets, beside desks, beneath stairs, waiting.

Turnover in the office is constant and quick. “I’ve seen someone leave a Post-it on her computer, ‘I quit,’ and never come back,” Ilia Morrows, a 29-year-old who has spent four years with the department, said. It wasn’t only the acute awareness that a child could be killed if you made the wrong decision — and that it could be you being named on the local TV news. It wasn’t only everyone’s knowledge of the summer before last: three deaths — a 14-year-old’s suicide; an infant’s suffocation, possibly accidental but definitely suspicious; a toddler’s baking to death in the back of a car — two in families under the watch of the Stamford office, the third in a family that had just moved to Stamford after being investigated and cleared by another D.C.F. office. It wasn’t only the knowledge of 7-year-old Nixzmary Brown, who had recently been allowed to remain with her family by New York City’s child-welfare system and was reportedly beaten to death by her stepfather. It was also the extreme authority, the burden of holding it, of wielding it, the prerogative to enter a family’s home and split it apart. “It’s almost hard to comprehend that we have that ability,” Morrows said. “It’s so huge.”

The staff is made up of investigators and treatment workers, with investigators handling the initial unannounced knock on the door after a report of abuse or neglect comes into the state’s hot line. Investigators have up to 45 days to decide whether to take a kid into D.C.F. custody, or to leave him at home but compel the family to accept the department’s long-term help, or to deem a report unsubstantiated and let the case go. During this time they can enter the house again and again and interview school nurses and neighbors, anyone who might know how well or terribly a child is being cared for. To take control of a child for longer than four days, the department needs a judge’s approval, but if a social worker senses that a child is at immediate risk, a supervisor’s signature on a form known as a “96-hour hold” will let her walk away with that boy, that girl or all the children in the house.

'I went home thinking, How do I have this power?' one child-welfare social worker said. 'In this state, in this country, the government can come in and take your kids. Tell you're unfit to take care of your kids. It was earth-shattering to me. It rocks you to core.' |

Johnson is in the treatment unit, which inherits cases from investigations and focuses not only on the protracted evaluation of families but also on guiding and, ideally, strengthening them so that children don’t have to be removed or so that those who have been seized can be returned. (“Reunification,” as it is called, is the outcome for about half of the 3,000 children D.C.F. takes into its care each year statewide.) A treatment worker might send an abusive father to group counseling for men who batter, a mother like Marie to a hospital program for substance abusers, a child to individual therapy, all with private providers under contract with D.C.F. But to be part of the treatment unit does not mean that you don’t take kids. Morrows, who is now in investigations, told me that during her first year with D.C.F., in another office, she had a treatment case with a family whose three children — an 11-year-old girl and boys who were 9 and 8 — suddenly confided that their father, an alcoholic, was coming home drunk, waking them and forcing them to kneel on rice or punching them in the stomach. If they doubled over from his blow, he commanded them to stand bent that way for long periods until he allowed them to straighten.

“You can’t do this, you can’t take my babies!” Morrows remembered the mother pleading, collapsed in agony on the floor, when Morrows tried to invoke a 96-hour hold after the father refused to move out of the home and the mother would not leave with the kids. “Do something!” the mother screamed at her husband. Outside the apartment, neighbors gathered in the hallway of the run-down complex — ominously, Morrows said, because D.C.F. is a known and not very welcome agency in the city’s poor neighborhoods. Slightly built and self-restrained, she waited. On her cellphone with her office, she was told that the police were on their way. But now, amid the mother’s sobbing, the kids told Morrows they would not go, that everything they’d said was a lie. The police, when at last they arrived, had to grab the children, lifting them in their arms. Two of the kids clung to the frame of the front door with both hands as they were carried out. The cops had to pry at their fingers, wrestle their bodies through. Skip to next paragraph Readers’ Opinions Forum: Parenting Where should social services draw the line on taking children away from their parents?

“I almost started giggling hysterically,” Morrows said, describing how she nearly broke down. “I really wanted to sit on the floor with Mom and cry.” Then she recalled her feelings hours later, in the aftermath of what had been her first removal: “I was shocked at what my job is, at the career choice that I had made. I went home thinking, How do I have this power? In this state, in this country, the government can come in and take your kids. Tell you you’re unfit to take care of your kids. It was earth-shattering to me. It rocks you to your core.”

Johnson, in her work with Marie and her boys, longed to turn away from this power. Talking about Marie, she didn’t begin with the present, with the clean drug tests; she began, emphatically, with the past, focusing on the crack addiction of Marie’s mother. From that, as Johnson told it, anarchy had taken hold of Marie’s life: the first child at 13; the group home; charges for robbery; time spent incarcerated; marriage to a drug dealer; the dealer’s fathering Antonio and Anthony before being deported to the Dominican Republic; the birth of Christopher, whose father was a drug addict (three men had fathered Marie’s first four boys); the marijuana in Christopher’s system when he was born; the addict’s trying to rob Marie in front of the children, wielding a gun, beating her.

Johnson wasn’t yet with the department at the time of this assault, but she knows the case record deeply and, at her desk in the spring, recounted the history to me in quiet tones of pain and near-helplessness. Above her head, Antonio’s pirate ship sailed off toward the horizon, while Anthony’s Ninja Turtle gazed down on her like a minute talisman the child had given to his protector to ensure that she do well on his behalf. In October 2003, a few weeks after the assault by Christopher’s father, Marie’s oldest son, Joseph, then 13, ran away from home and was gone for three days. “He alleges,” the case record states, “that mother hits and punches him in the face. . .that mother has kept him home from school to watch younger children and clean house while she goes somewhere.” Then, in December 2004, Marie had Diomedes, by yet another man, and the newborn, six weeks premature and weighing three and a half pounds, had cocaine running through his body and brain. Soon the case was Johnson’s, and it wasn’t long before she was praying over a prospect, T.P.R., she could hardly bear to contemplate. “I asked God to enlighten me,” she said. “I asked God for help.”

Parens patriae is the legal principle, about four centuries old, that lies behind cases like Marie’s. It lies behind the child-welfare investigations into the families of three and a half million children in the United States in 2004 (the last year for which statistics are available). Each year around 300,000 children are temporarily removed and 65,000 to 70,000 of those children are ultimately taken from their parents forever, according to the Department of Health and Human Services. Parens patriae is the doctrine that empowers government institutions to venture into the intimate realm of child-rearing and effectively deputizes social workers like Annette Johnson and Ilia Morrows to knock on the doors of family homes and gain entry. Translated from Latin, parens patriae means “parent of the country”; it entrusted the king of England to be the “general guardian,” in the words of the 18th-century legal scholar William Blackstone, “of all infants, idiots and lunatics,” of all who were helpless.

In colonial America, when parents viewed their children, far more than they may now, as economic assets, as laborers essential to the family’s survival, parens patriae played out differently than it does today. Offspring were a family’s property, and public authorities kept their distance, according to Brenda G. McGowan, professor of social work at Columbia University. The primary exceptions were orphans and the children of paupers, who were often put in almshouses until they turned 8 or 9. Then they were old enough to be indentured.

|

|||||

|

Not until the mid-19th century did American society begin to see itself as responsible, in any modern sense and on any vast scale, for rescuing desperate children. Compelled by the destitution of New York City’s thousands of street kids, Charles Loring Brace, a Methodist minister, founded the Children’s Aid Society in 1853, proclaiming, “The great duty is to get these children of unhappy fortune utterly out of their surroundings and to send them away to kind Christian homes in the country.” He and his staff knocked on the doors of shacks and tenement rooms, persuading impoverished parents to sign their children over to the society and loading them, along with children from orphanages, onto the nation’s new trains, headed West. A few days later, in distant towns, where farmland was plentiful and labor was scarce, the children climbed down from the locomotive cars to be lined up on the stages of meeting halls. Farmers squeezed muscles and prodded teeth before agreeing to take them on as members of their families. Skip to next paragraph Readers’ Opinions Forum: Parenting Where should social services draw the line on taking children away from their parents?

By the program’s end in 1929, more than 100,000 children had ridden toward new homes. Members of the Catholic clergy saw Brace’s system as a way to snatch the Catholic children of the urban poor and convert them to the Protestantism of the hinterlands. Other critics made comparisons to the slave trade. But Brace, with his vision of saving the young by settling them in redemptive homes, is credited as a kind of founder of foster care.

It is the story of a lone 9-year-old girl, though, that stands as the symbolic beginning of work like Johnson and Morrows’s. Mary Ellen Wilson “stood washing dishes, struggling with a frying pan about as heavy as herself,” wrote the missionary who discovered her in a Manhattan tenement in 1873. “Across the table lay a brutal whip of twisted leather strands, and the child’s meager arms and legs bore many marks of its use.” The girl’s neighbors had told the missionary about the way she was kept locked in an inner room and was never seen outside — the neighbors didn’t know how to help, and neither did the missionary once she talked her way past the girl’s caretaker (whom the girl called Mamma but who was not her natural mother) at the apartment’s door and had a glimpse of the waif. The missionary was “tempted to apply to the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals,” she wrote, but she “lacked courage to do what seemed absurd.” The absurd was her only resort, though, and at last she went to the society’s president in New York and persuaded him to take the case. He sent an agent, posing as a census taker, to gain access to the apartment and gather evidence on the girl’s condition. Mary Ellen’s caretaker was sent to prison after a highly publicized trial in 1874; the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children was started that same year; and similar organizations — privately run but heeded by the police and the courts — quickly sprang up around the country.

Beginning in the late 19th century, driven partly by a growing middle class that could afford to see children as innocents in need of protection rather than as miniature members of the work force and spurred, too, by a multiplying — and, to many, frightening — immigrant population that seemed in dire need of socialization, the American public intervened more and more in the way the nation’s children were raised. Government agencies replaced the private organizations in the early 20th century. And since the 1960’s, according to Martin Guggenheim, a professor at New York University School of Law, the exercise of authority by those agencies to enter the sphere of child-rearing — and to sever children from their parents — has surged, propelled by public-health campaigns against child abuse, by media attention to the relatively rare horrific deaths of children from maltreatment in the home and by a quest for swift conclusions, for “permanency,” as child-welfare workers call it. Prevailing developmental theory urges that children of parents like Marie should not be allowed to languish long in temporary care while their mothers (the fathers are often secondary figures, at best) try to redeem themselves and reclaim their kids. So while the goal known as “family preservation” generates a steady supply of newly designed programs, and while the field of child social work is in constant search for a panacea to keep families together, present policy thinking also reflects a conflicting idea: kids should be channeled efficiently toward adoption.

At the level of policy, the emphasis on speed has been influenced not only by developmental theory but also, as Guggenheim sees it, by a confluence of left- and right-wing agendas — by children’s rights advocates, who tend to view the interests of the child in opposition to those of the parents, and by fiscal conservatives reluctant to spend money on lengthy efforts to help underclass women sort out their lives. In 1997, Congress passed the Adoption and Safe Families Act, which links federal money to states’ efforts to move children toward adoption after they have been in temporary care for 15 of any 22 months. Across the country, between 1997 and 2003 (the most recent year for which statistics are available), adoptions through child-welfare agencies increased by more than 60 percent. The legislation honors the current wisdom that establishing new stability is more beneficial for the child than struggling for years, with uncertain results, to preserve the bond with the parent he has known. But one inherent effect is that in the domain of American child welfare, the doctrine of parens patriae is more powerful than it has ever been.

For two years before Diomedes’s birth in December 2004, D.C.F. investigated and chronicled the chaos of Marie’s life with her sons, but it monitored more than intervened, and eight months before Diomedes was born it closed the case, partly because Marie had compliantly gone to be evaluated by a substance-abuse program, which determined that she didn’t need treatment, and partly because her household could sometimes seem, to visiting D.C.F. staff members, to be tranquil, with one report noting Antonio doing his homework and, at his mother’s direction, obediently pouring orange juice for his younger brother Anthony.

Premature and positive for cocaine, Diomedes spent his first month in the hospital, and the department was ready to take all of Marie’s kids until she got herself clean. But Marie’s mother, who shed her crack addiction years earlier, volunteered to move into Marie’s house and care for the five boys while her daughter underwent treatment. At the time, D.C.F. knew nothing about the mother’s history; records of her having deserted her own children were buried within old files kept by the child-welfare system of New York City, where Marie grew up. And D.C.F. always tried to find relatives to parent the kids it would otherwise have to put in foster homes, so the children’s lives could remain as steady and familiar as possible.

“It was Monday, April 11, at 2:15,” Johnson said, remembering the precise moment in 2005 when, about four months after stepping in as caretaker, Marie’s mother walked into the D.C.F. office with Antonio and Anthony, Christopher and Diomedes. She had apparently given up on Marie’s oldest, Joseph, a week or so earlier, placing him at a local shelter called Kids in Crisis. Now — with Marie having just relapsed in an outpatient program, falling back into using cocaine and having disappeared — she announced to Johnson that the remaining four were too much to handle, that she was finished. “I begged her,” Johnson recounted, “please don’t do this, don’t do this to these children, you don’t know what this will do to them.” Marie’s mother kissed the boys, turned and walked out of their lives.

“Even now,” Johnson said, “I feel a little tremor over the grandmother bringing them here, a strange office building, and leaving them. I was in shock.” Then she described Antonio’s reaction. Seven years old at the time, he seemed to understand exactly the magnitude of what had just happened. “He just stared out the window. ‘Do you want to eat?’ ‘No.’ ‘Do you want to play with something?’ ‘No.’ I took him to stay at Kids in Crisis, hoping that seeing his brother there would help. He put a Venetian-blind cord around his neck and jumped off a chair. He spent months on the child psych ward in Yale New Haven Hospital he was so depressed.”

Diomedes was taken to one foster home, Anthony and Christopher, then 5 and 2, to another. Licensed foster homes are in such short supply, and space within them is so scarce, that the siblings couldn’t be kept together. On the afternoon that Marie’s mother abandoned the boys to D.C.F., the Stamford office’s “matcher” worked her phone. Right away, whenever the office takes custody of a child, the matcher calls her list of local foster homes, and then her list of less local ones, an hour or more away, to see if any might be willing to take another kid, even if there isn’t quite enough room, let alone enough energy. On that afternoon, she could find only a Spanish-speaking foster mother for Anthony and Christopher, who don’t speak Spanish. In the woman’s home, over the next weeks, Anthony repeatedly beat his head against the walls until his nose bled. He drove a hole in a wall with his shoulder. The foster mother threw water in his face to purge him of demons. Johnson begged the matcher to somehow conjure a new placement.

Meanwhile, Marie seemed to purge something in herself. She fought to get control of her addiction. “It was the best thing that ever happened to me,” she told me — the realization that she could lose her children permanently, though at that point no move toward T.P.R. had been taken. “I woke up.” She worked her way through a five-week inpatient program. Anthony and Christopher were moved to a better foster home. Johnson took all the boys on special outings — to a children’s museum, to the fantasy-land restaurant Chuck E. Cheese’s — to make sure they had a constant in their lives. She grew to adore them. She drove up to New Haven twice a week to visit Antonio in the hospital where he was being treated for depression and to take him for haircuts or clothes shopping. She had faith that the family could eventually be put back together. Marie graduated to outpatient sessions. “Mother,” Johnson wrote in a report after overseeing a weekly visit in July 2005, “was appropriate with children and appeared bonded and showed affection.”

'I feel this is in the best interests of the children,' Johnson told me, busy drafting a petition requesting parental termination. She had come a long way from her ardrnt hope of never having to tear a child permanently from its family. And she addeded, 'I think of my role now as saving children's lives, not just helping families.' |

Then, in October, Johnson; two of her supervisors; Stamford’s director, Ken Mysogland; a D.C.F. lawyer; a clinical social worker; and a behavioral-health specialist met for a formal review of the case, to reckon with its history for the first time in a completely comprehensive way. Johnson heard that the others didn’t share her hope. (Like her, they had come to cherish the kids, Mysogland greeting Christopher with great fanfare as “Handsome!” whenever the boy was in the office.) They saw four kids who were acutely fragile, with fissures running through their psyches, and a mother who was too broken to ever help them heal. “Too high risk, with the emotional instability of the boys,” Mysogland told me when I asked why, given that Marie had by October been testing clean for several months, they hadn’t envisioned returning the boys to her eventually and providing a period of extensive support to assist her as a mother. “We can load up on services if Mom is capable of meeting her kids’ needs.” He didn’t see her as potentially capable, despite the nascent signs of change. He weighed the history of substance abuse and violent men, not only Christopher’s father but also Diomedes’s father, who had once cut Marie’s phone cord with a kitchen knife when she demanded that he leave her house. Mysogland also dwelled on his sense that Marie could not cope with the special needs of her children, like Antonio’s A.D.H.D., and on his “surmise” that she suffered from mental illness (though, as she would later ask me, “If I had mental illness, don’t you think you would have seen me break down by now, after all they’re putting me through?”). The pressure of the boys in her home, he reasoned, would only add to the odds that she would falter, wounding them again. At the meeting, Johnson heard that the department would hire an outside evaluator to confirm their assessment; her superiors believed termination was likely. She began praying — “to help me understand why we’re doing this.” Skip to next paragraph Readers’ Opinions Forum: Parenting Where should social services draw the line on taking children away from their parents?

The anguish and incredulity returned quickly to Johnson’s voice as she remembered: “I was like, but she’s doing what we asked her to do. The urine’s come back clean, the hair test has come back clean.” Yet her prayers were, more or less, answered. Slowly she learned to think less about Marie’s keeping away from drugs than about signs that her life would remain dangerously anarchic. Johnson focused on a car accident in August 2005 that left Marie’s leg in a cast — Marie told her that a New York bus had hit her stationary car, but in October, Johnson learned from city records that witnesses had seen Marie driving fast and erratically before running into the bus with her vehicle. And Johnson focused on domestic violence. In December, her face bruised, Marie told Johnson that she had been mugged and pistol-whipped in the Bronx, but Johnson later found out from the Bronx district attorney’s office that Marie’s boyfriend, Diomedes’s father — who had recently served several months in prison for kicking a police officer during an arrest on other charges, which were eventually dropped — had been picked up for beating Marie on the street. This same man was also the father of the unborn child Marie was now carrying.

Johnson concentrated on Marie’s recklessness, her men, her lies. What if the boys were in the next car that crashed? What if the violence of Marie’s lovers turned against her children? Johnson made her peace with the opinion of her superiors, an opinion affirmed by the outside evaluator. Acceptance was made far easier by the fact that Antonio, who was by then out of the hospital, Anthony and Diomedes would probably each be adopted into his current foster home and that Christopher would go to a paternal uncle, a retired policeman. “I’m 100 percent now,” she told me, and compared the oldest and youngest of the boys. Joseph had been uncontrollable while living at Kids in Crisis. He had gotten so drunk that he passed out on the lawn in front of his school. He had smashed up the shelter’s kitchen, been placed in a detention center and then, in October, after being driven by Johnson to an interview at a residential facility, had asked her to buy him a strawberry milkshake at McDonald’s. He fled from the restaurant and has been missing ever since. Johnson imagined his life now as utterly lost, and said, “His mother made him the boy that he is.” She envisioned Diomedes’s life as full of promise — starting with the promise of adoption.

The four boys would be separated. All of the potential adoptive parents seemed agreeable to keeping them in contact with one another and, perhaps, with Marie, though there would be no legal guarantee that she could ever see them or even talk with them by phone. “I feel this is in the best interests of the children — T.P.R.,” Johnson told me, busy drafting the petition to the court. She had come a long way from her ardent hope of never having to tear a child permanently from its family. And she added, “I think of my role now as saving children’s lives, not just helping families.” The distinction was not subtle. She had, in this way, reconciled herself to the extreme authority of her work.

'I believe in the golden rule," said Martin Guggenheim — the N.Y.U. law professor, who represented hundreds of kids in juvenile-delinquency, child-protection and T.P.R. cases as a legal-services attorney — when I described Marie’s situation. “Test this case against what we would want for our own families.” He spoke about race and class and suggested that we substitute someone influential for Marie and painkillers for cocaine. “If we imagine it was substances that important people use, we can’t imagine that we would be taking those children.”

Nationally, two-thirds of child removals are cases of neglect. (Marie’s case falls into this category.) Neglect — not battering, not sexual molestation. The preponderance of neglect cases dates back to the child-welfare work of the late 19th century, Guggenheim said, with its compulsion to rescue children from the alien and impoverished ways of their immigrant families. Objective delineations of neglect are difficult to draw, and poor and minority parents are left particularly vulnerable to agency excesses and misjudgments. A court-appointed lawyer may be assigned when an agency moves to take custody or terminate rights, but this can hardly make up for a parent’s lack of wherewithal. “When should the state exercise its awesome power in severing parental ties?” Guggenheim asked. “Only when we are absolutely certain. Because history tells us that the exercise of that awesome power will be carried out against the least privileged of our society.”

The Stamford D.C.F. office — with its profusion of stuffed ducks and donkeys and bears sitting above desks — doesn’t look much like a center of awesome and menacing state power. And it didn’t sound like one on a recent morning as Johnson talked about a 16-year-old girl who had been abandoned by her mother at 5 and whom Johnson had helped to rescue from alcoholism. “I’m happy to say,” Johnson told me, “that my girl is getting ready to graduate, and I’m getting ready to get some money to buy her a prom dress.” The department invests in the education of the kids it oversees; it will pay for college or graduate school until a client turns 23, and it will pay for rites of passage like senior proms. Amanda Nowak, who sits in the cubicle next to Johnson’s, spoke about a teenager, a talented painter, she had coaxed from homelessness; Nowak would soon be taking her into Manhattan to visit art schools.

And most everyone seemed self-aware when it came to their authority and eager to avoid abusing it. Nowak had just given up a string of Saturdays, working successfully to return three children to a cocaine-abusing mother who appeared to have turned her life around. Mysogland, the agency’s director, told stories about growing up as one of three biological children of parents who adopted eight others. There was the boy who had been abused and who would booby-trap his bedroom in the Mysoglands’ house to keep himself safe. There were the pair of brothers who had lived in 26 foster homes. The younger one had been born addicted to heroin and brain-damaged. Mysogland, whose pale shaved head accentuates his energy and earnestness, remembered that the older one had jumped over and over from a therapist’s couch into Mysogland’s mother’s arms: an exercise to develop the beginnings of trust. “But I’ve learned not to apply my family too much in informing my decisions,” he said. “This is the most intrusive work. Imagine telling a mother, ‘You’re never ever seeing your kids again.’ Every morning when I turn on the light in this office, I have to put my personal stuff aside. I have to say, Adoption may have been great for my siblings, but it may not be the right decision always.”

Self-awareness seemed to permeate department thinking about race and class as well. One morning, Connecticut’s D.C.F. commissioner, Darlene Dunbar, spoke to the Stamford staff about “disproportionality and disparate outcomes.” Of the 6,300 kids currently in the department’s custody, approximately 24 percent are black, almost twice the percentage of black minors in the state’s population, and 35 percent are Hispanic, more that three times the percentage in the populace. (Nationally, black children are similarly overrepresented. Hispanics are less so, though they are taken into state care at higher rates than whites.) These numbers, perhaps, represent social and economic forces beyond any child-welfare department’s control. But another set of Connecticut figures, comparing the rates at which white, black and Hispanic families are investigated with the rates at which their kids are taken, at least temporarily, by D.C.F., are more alarming. Investigated white families are broken apart least often, then black families, then Hispanic — at twice the rate for whites.

No one tried to hide the problem, though no one was sure how to solve it. “When a family presents as more articulate and can gather resources easier,” Mysogland wrote me in an e-mail message after we talked about these numbers, “whether those resources are family or finances or provision of services, that changes the overall level of risk or the perceived level of risk. Families that obtain aggressive legal counsel can influence the way the department wants to proceed with a case and the overall outcome of our interventions. We may examine the information a little closer if the family is high profile or wealthy, given that we know they will most likely vigorously oppose the department’s decision. We see this in our work, and it would be unethical and dishonest for us to say these issues are not true. We try to give everybody the right types of services. But the statistics tell us we have more work to do.”

Still, behind the thoughtfulness and candor that pervaded the office, and despite everyone’s best intentions, something disconcerting hovered around the work: a hint of hubris that had the potential, perhaps, to be as destructive as any abusive boyfriend, as any drug. This force felt all but inevitable; Mysogland only happened to be the one to give it voice, as he declared that he had no doubts about the department’s decision in Marie’s case. He readily acknowledged that the Adoption and Safe Families Act drove the department toward faster resolutions, created a momentum toward T.P.R. and adoptions and increased the impact of D.C.F. on families. On balance, all this was a good thing, as he saw it; the law took into account “a child’s sense of time,” the mantra of developmental psychology that is cited frequently in the child-welfare field, stressing a child’s urgent need for clarity, for security, for finality, even at the brutal cost of sacrificing his hope of returning to his original family. When Mysogland discussed Marie’s family, though, any talk of the influence of legislation was beside the point. The statistics about Hispanics in the system were equally irrelevant. On the subject of Marie’s boys, his speech was often plain and tough. “Those kids are damaged,” he told me. “Not broken bones, but broken brain parts.” Marie was simply not — and would not be — fit to mother them. When I asked about the unborn baby, Mysogland’s tone was even more definite. He emphasized a newborn’s extreme vulnerability, then stated, “Some people just should not be parents.”

After I’d spent many weeks with the department, I learned that the foster mother who plans to adopt Diomedes is a D.C.F. attorney in another part of the state. Mysogland didn’t see this as a conflict of interest; in his eyes, her work with the department made her only more attractive as an adoptive parent, because of her familiarity with the damage that kids taken into D.C.F. care have suffered. But while this made a kind of sense, it was hard not to think of Martin Guggenheim’s vision and of a hyperbolic-sounding phrase he had used, “social engineering.” It was hard not to consider that a highly privileged woman was being substituted for a terribly flawed but fiercely determined mother.

And it was hard not to think back to Marie’s picnic visit, when Anthony had spoken words that seemed scripted, though there was almost no way they could have been. He may simply have been cued by all that was in the air. “She shares,” he proclaimed, as Marie served chicken, rice and peas to me as well as to her boys. “If that was your mommy, you would be lucky.” Skip to next paragraph Readers’ Opinions Forum: Parenting Where should social services draw the line on taking children away from their parents?

"Come here, white boy,” Marie said to Christopher, in one of the visiting rooms late in May, seven weeks after I first met her. “Come here, gringo.” She wrapped her fair-skinned, blond 3-year-old in a hug.

“I want to be gringo,” 6-year-old Anthony complained, his dark brown eyes and light brown face looming dejectedly over the puzzle he and Marie had been working on.

“You can’t be gringo,” she said.

“I’m gringo,” he insisted.

She pulled him into a hug too. “Why you want to be gringo? You want to be you.”

Then, at the end of the visit, Antonio, Anthony’s older brother, broke down. A half-hour earlier he asked for a cellphone, and Marie said she would try to buy him one, but Johnson took her aside and told her that Antonio, at 8, was too young, that it wasn’t appropriate. Now the boy was sobbing, saying that a friend of his had one, and Marie told him: “You remember what Grandma said? If somebody’s got something on their head, you going to stick something on your head? Don’t worry about what somebody got. Think about what you got. Mommy’s here. You gonna see me every visit.”

But the concept of “Mommy” was about to become more complicated than it already was. Though the court hearings on termination were many months away, the department felt that it needed to tell at least the two older boys about the prospect of their being adopted, to avoid the chance of their hearing about it inadvertently from their foster parents or, in an outburst, from Marie. The telling began that afternoon with Anthony, when Johnson delivered him back to the home of the foster mother who planned to adopt him. A teenage girl, the foster mother’s niece, let them into the little blue clapboard house, its front yard surrounded by a chain-link fence, and Johnson followed Anthony upstairs to his room. She sat on the bed, he on the stained, once white carpet with a toy or two. She asked if he loved his foster mother.

“Pretty much,” he said, and added, “I like her very much.”

Listening, I recalled Marie’s raspy voice during another of our conversations in her kitchen, with the kids’ photographs on the refrigerator door: “What’s best for my kids? To come home with their mom. No other place is going to be home.” Diomedes, she went on, “is a baby. He does not know me. Real is what real is. But my other kids, they’re used to Mom doing things with them. O.K., where they’re at, they’re safe, I have no doubts. But what is the best thing? I’m here, I’m Mom. I need to see them, but they need me more than I could ever need them,” she said, as if she knew that in the all but omnipotent judgment of the department her own need carried no weight.

“My mom walked out on us behind drugs. I’m going to fight this until the end.”

One way to fight was to flee: by late June, Marie would tell Johnson that she had moved to New York and planned to deliver her baby there, so D.C.F. couldn’t take it. All the department would be able to do was alert New York’s child-welfare agency and hope it would open a case on Marie and the unborn child. Marie told Johnson that she would continue visiting her boys, but she missed her chances during the first two weeks of July and seemed, to the department, to be on the verge of vanishing.

But now in the bedroom of Anthony’s foster home, Johnson said to him, “This is going to be your new home.” Her voice was thin, a notch higher than usual, yet firm. Her face looked drained; her long, animated braids of hair could not bring it to life.

“Until my mom gets better?”

“Getting better” was the euphemism the department used with the children, to avoid spelling out the drug use, the domestic violence.

“Well, maybe your mom’s not getting better like she’s supposed to.” Johnson tried to keep the talk focused on his foster mother: “She’ll be the one that’s going to take care of you, just like she’s doing now.”

He opened the splintered door of his closet, revealing the mound of toys crammed haphazardly within. “Do you want to see my Batman clothes?” he asked her.

“Do you understand what I’m telling you?”

“That means she’s going to be the ruler of me. But how come I can’t stay with my mom if she gets better?”

“Because I’ve got to make a plan for you.” He took a bucket of Legos out of the closet.

“Do you understand what I’m telling you?”

“I don’t understand.”

Johnson paused, pulling her thoughts together as Anthony spilled the yellow and red pieces on the floor. “Remember one time we talked about going back? Right now we’re not talking about that anymore. This is the place that you’ll stay.”

“But when my mom gets better?”

“I’m not sure she’s going to get better. She’s been trying and trying and trying.”

Anthony didn’t reply. He turned over the bucket and the last of the pieces plummeted out. “Could you make a cowboy?” he asked. A Lego horseman was pictured on the side of the container.

Though she was dressed somewhat formally, Johnson lowered herself to the discolored carpet. She began to search for the pieces that would create his cowboy. “This could take some time,” she said.

He seemed to consider those words. Perhaps the same language had been used with him once about his mother’s recovery and his return to her. And now he was being told new words — that his mother had, in the end, failed, that it was not going to happen, ever. He seemed to wish for the old words, the old reality and, as he spoke, to dart backward in time to a point when the promise of effort had been enough. “But you’ll try?” he asked, his voice almost silent, as if he were addressing a mother only he could see. “I will.” «

Daniel Bergner, a contributing writer, is the author of “In the Land of Magic Soldiers: A Story of White and Black in West Africa.” His last article for the magazine was about a missionary family in Africa.

Copyright 2006 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times Magazine of Sunday, July 23, 2006.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |