But Mr. Duvalier’s risky return home from France may have been driven by another motivation: money.

Though Mr. Duvalier has long been accused of looting $300 million from Haiti before fleeing nearly 25 years ago, his lawyers and friends have said that much of his money was squandered on a lavish lifestyle of jewelry, chateaus, fancy cars and a very expensive divorce from his ex-wife.

Just this week, one of Mr. Duvalier’s lawyers said that when his client was hauled before a Haitian court and asked how he supported himself, Mr. Duvalier responded: “With the help of friends.”

But about $6 million still sits frozen in an account in Switzerland, and Mr. Duvalier has publicly vowed to make every effort to get it. Haitian officials, human rights advocates and political analysts believe that Mr. Duvalier came back to the country last weekend for the sole purpose of making an end run around a new law that will make it harder for him to do that.

“This was a gamble, plain and simple,” said an analyst, who asked not to be identified because he was close to the Haitian government and was not authorized to speak publicly. “He gambled because his money is low and his health is failing, so what did he have to lose?”

The strategy has backfired. In a striking scene, Mr. Duvalier was taken out of his hotel by heavily armed police officers on Tuesday and formally charged with corruption and embezzlement during his nearly 15-year rule.

A lawyer for Mr. Duvalier, Gervais Charles, acknowledged that things had not gone well for his client. While Mr. Charles said he had not discussed the motivations behind Mr. Duvalier’s abrupt homecoming, he dismissed the new charges as part of Haiti’s efforts to keep Mr. Duvalier from getting the money, adding that Mr. Duvalier wanted the funds simply so that he could donate them to the Red Cross’s earthquake relief efforts.

“I don’t think this was a very successful trip,” he said.

The money has long been a source of international contention. Last year, only hours before the earthquake that devastated Haiti, Switzerland’s top court ruled that at least $4.6 million should be released to the Duvaliers, prompting an outcry when the ruling was published.

Swiss officials, eager to clean up the country’s image as a depository for dictators, responded to the uproar by quickly passing what is known as the Duvalier Law, giving them more discretion to return ill-gotten gains to the countries they were stolen from.

But the new law does not go into effect until Feb. 1, which may explain the timing of Mr. Duvalier’s bold move. Under the current rules, states making claims to money in Switzerland must show that they have begun a criminal investigation against the suspected offender before any funds can be returned.

So if Mr. Duvalier had been able to slip into the country and then quietly leave without incident, as he was originally scheduled to do on Thursday, he may have been able to argue that Haiti was no longer interested in prosecuting him — and that the money should be his.

“This was probably a calculation on Duvalier’s part, that the state was so weak that he could return to Haiti and leave without being charged with anything,” said Reed Brody, a lawyer and spokesman for Human Rights Watch. “Then he could go back to Swiss authorities and argue that he should get his money because Haiti’s not after him anymore.”

The Duvalier Law will change that, allowing Swiss authorities to send the money to Haiti on the grounds that the country, the poorest in the Western Hemisphere, is too weak to prosecute Mr. Duvalier, particularly since he has been living in France, far out of the reach of Haiti’s weak justice system.

A year after Haiti was hit by an earthquake that killed more than 200,000 people and left a million people homeless, this country seemed ripe for a legal ambush. Cholera is on the prowl. The government remains in disarray and the political landscape turned volatile after last year’s contested presidential elections.

Upon arriving Sunday, Mr. Duvalier told reporters that he planned to stay only for a few days. Then he and a close circle of friends and relatives holed up in a high-end hotel in the hills overlooking the capital.

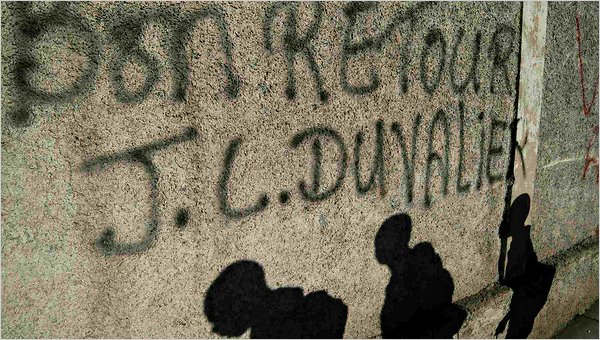

But his return prompted calls for justice from international human rights groups, a handful of Haiti’s allies and a growing number of the people who were kidnapped and tortured by Mr. Duvalier’s repressive government.

By Tuesday, the Haitian government was compelled to act, formally presenting charges against Mr. Duvalier, known as Baby Doc, and ordering him not to leave to country while a judge determined whether to send him to trial. The next day, a handful of journalists and community leaders detained and tortured by Mr. Duvalier’s special militia — known as the Tonton Macoutes — filed individual complaints against Mr. Duvalier and called on other victims to do the same.

“What’s important isn’t how this all turns out,” said Michèle Montas, a former radio journalist who was detained for a week in 1980 and then forced to flee the country. “What’s important is the journey.”

Later, another former victim, Alix Filsaime, said, “What we’re saying here is, ‘Never again.’ ”

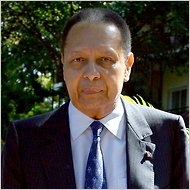

Though still tall and erect, Mr. Duvalier seems a shadow of the chubby-cheeked playboy who took over this country at the age of 19, after the death of his father, François Duvalier, known as Papa Doc. He has long suffered from Lupus, and some contend that he now has pancreatic cancer.

Asked if Mr. Duvalier regretted having returned home, Mr. Charles, his lawyer, shrugged and said, “He was surprised that so many young people, who didn’t know him when he was president, came and cheered for him. But many people were outraged, too, and now there are the judicial issues.”

“He must have mixed feelings about it,” Mr. Charles said.