| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted Septeber 24, 2008 |

| Seeing Past The Slave To Study The Person | |

|

|

|

|

|

| Annette Reed-Gordon | |

|

|

| By PATRICIA COHEN |

|

|

|

|

|

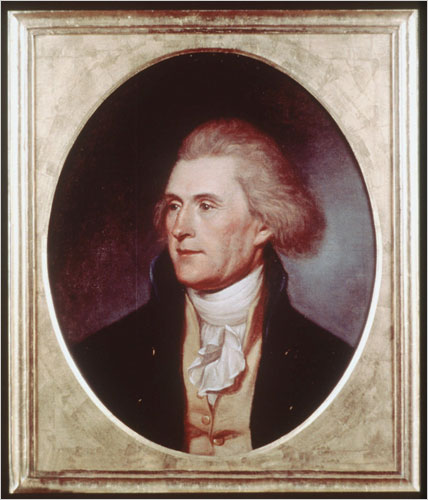

| LIBRARY OF CONGRESS | |

| Thomas Jefferson, president and slave owner. | |

|

|

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |