| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted December 19, 2005 |

|

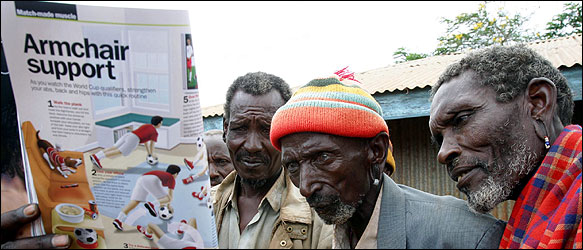

Francesco Broli for The New York Times |

| Johana Mkoro, center, and Nkarunga Learapo, right, study a Western health magazine in Sanga, Kenya. |

| Remote and Poked, Anthropology's Dream Tribe |

____________ |

By MARC LACEY |

LEWOGOSO LUKUMAI, Kenya - The rugged souls living in this remote desert enclave have been poked, pinched and plucked, all in the name of science. It is not always easy, they say, to be the subject of a human experiment.

"I thought I was being bewitched," Koitaton Garawale, a weathered cattleman, said of the time a researcher plucked a few hairs from atop his head. "I was afraid. I'd never seen such a thing before."

Another member of the tiny and reclusive Ariaal tribe, Leketon Lenarendile, scanned a handful of pictures laid before him by a researcher whose unstated goal was to gauge whether his body image had been influenced by outside media. "The girls like the ones like this," he said, repeating the exercise later and pointing to a rather slender man much like himself. "I don't know why they were asking me that," he said.

Anthropologists and other researchers have long searched the globe for people isolated from the modern world. The Ariaal, a nomadic community of about 10,000 people in northern Kenya, have been seized on by researchers since the 1970's, after one - an anthropologist, Elliot Fratkin - stumbled upon them and began publishing his accounts of their lives in academic journals.

Other researchers have done studies on everything from their cultural practices to their testosterone levels. National Geographic focused on the Ariaal in 1999, in an article on vanishing cultures.

But over the years, more and more Ariaal - like the Masai and the Turkana in Kenya and the Tuaregs and Bedouins elsewhere in Africa - are settling down. Many have migrated closer to Marsabit, the nearest town, which has cellphone reception and even sporadic Internet access.

The scientists continue to arrive in Ariaal country, with their notebooks, tents and bizarre queries, but now they document a semi-isolated people straddling modern life and more traditional ways.

"The era of finding isolated tribal groups is probably over," said Dr. Fratkin, a professor at Smith College who has lived with the Ariaal for long stretches and is regarded by some of them as a member of the tribe.

For Benjamin C. Campbell, a biological anthropologist at Boston University who was introduced to the Ariaal by Dr. Fratkin, their way of life, diet and cultural practices make them worthy of study.

|

Francisco Broli for The New York Times |

| In Songo, Koitato Carawale, left, was amused at delicate questions by Danielle Lemoille, a research assistant. |

Other academics agree. Local residents say they have been asked over the years how many livestock they own (many), how many times they have had diarrhea in the last month (often) and what they ate the day before yesterday (usually meat, milk or blood).

Ariaal women have been asked about the work they do, which seems to exceed that of the men, and about local marriage customs, which compel their prospective husbands to hand over livestock to their parents before the ceremony can take place.

The wedding day is one of pain as well as joy since Ariaal women - girls, really - have their genitals cut just before they marry and delay sex until they recuperate. They consider their breasts important body parts, but nothing to be covered up.

The researchers may not know this, but the Ariaal have been studying them all these years as well.

The Ariaal note that foreigners slather white liquid on their very white skin to protect them from the sun, and that many favor short pants that show off their legs and the clunky boots on their feet. Foreigners often partake of the local food but drink water out of bottles and munch on strange food in wrappers between meals, the Ariaal observe.

The scientists leave tracks as well as memories behind. For instance, it is not uncommon to see nomads in T-shirts bearing university logos, gifts from departing academics.

In Lewogoso Lukumai, a circle of makeshift huts near the Ndoto Mountains, nomads rushed up to a visitor and asked excitedly in the Samburu language, "Where's Elliot?"

They meant Dr. Fratkin, who describes in his book "Ariaal Pastoralists of Kenya" how in 1974 he stumbled upon the Ariaal, who had been little known until then. With money from the University of London and the Smithsonian Institution, he was traveling north from Nairobi in search of isolated agro-pastoralist groups in Ethiopia. But a coup toppled Haile Selassie, then the emperor, and the border between the countries was closed.

So as he sat in a bar in Marsabit, a boy approached and, mistaking him for a tourist, asked if he wanted to see the elephants in a nearby forest. When the aspiring anthropologist declined, the boy asked if he wanted to see a traditional ceremony at a local village instead. That was Dr. Fratkin's introduction to the Ariaal, who share cultural traits with the Samburu and Rendille tribes of Kenya.

Soon after, he was living with the Ariaal, learning their language and customs while fighting off mosquitoes and fleas in his hut of sticks covered with grass.

The Ariaal wear sandals made from old tires and many still rely on their cows, camels and goats to survive. Drought is a regular feature of their world, coming in regular intervals and testing their durability.

"I was young when Elliot first arrived," recalled an Ariaal elder known as Lenampere in Lewogoso Lukumai, a settlement that moves from time to time to a new patch of sand. "He came here and lived with us. He drank milk and blood with us. After him, so many others came."

Over the years, the Ariaal have had hairs pulled not just from their heads, but also chins and chests. They have spat into vials to provide saliva samples. They have been quizzed about how often they urinate. Sometimes the questioning has become even more intimate.

Mr. Garawale recalls a visiting anthropologist measuring his arms, back and stomach with an odd contraption and then asking him how often he got erections and whether his sex life was satisfactory. "It was so embarrassing," recalled the father of three, breaking out in giggles even years later.

Not all African tribes are as welcoming to researchers, even those with the necessary permits from government bureaucrats. But the Ariaal have a reputation for cooperating - in exchange, that is, for pocket money.

"They think I'm stupid for asking dumb questions," said Daniel Lemoille, headmaster of the school in Songa, a village outside of Marsabit for Ariaal nomads who have settled down, and a frequent research assistant for visiting professors. "You have to try to explain that these same questions are asked to people all over the world and that their answers will help advance science."

The researchers arriving in Africa by the droves, probing every imaginable issue, every now and then leave controversy in their wake. In 2004, for instance, a Kenyan virologist sued researchers from Britain for taking blood samples out of the country that he said had been obtained from a Nairobi orphanage for H.I.V.-positive children without government permission.

The Ariaal have no major gripes about the studies, although the local chief in Songa, Stephen Lesseren, who wore a Boston University T-shirt the other day, said he wished their work would lead to more tangible benefits for his people.

"We don't mind helping people get their Ph.D.'s," he said. "But once they get their Ph.D.'s, many of them go away. They don't send us their reports. What have we achieved from the plucking of our hair? We want feedback. We want development."

Even when conflicts break out in the area, as happened this year as members of rival tribes slaughtered each other, victimizing the Ariaal, the research does not cease. With tensions still high, John G. Galaty, an anthropologist at McGill University in Toronto who studies ethnic conflicts, arrived in northern Kenya to question them.

In a study in The International Journal of Impotence Research, Dr. Campbell also found that Ariaal men with many wives showed less erectile dysfunction than did men of the same age with fewer spouses.

Dr. Campbell's body image study, published in The Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology this year, also found that Ariaal men are much more consistent than men in other parts of the world in their views of the average man's body and what they think women want.

Dr. Campbell came across no billboards or international magazines in Ariaal country and only one television in a local restaurant that played CNN, leading him to contend that Ariaal men's views of their bodies were less affected by media images of burly male models with six-pack stomachs and rippling chests.

To test his theories, a nonresearcher without a Ph.D. showed a group of Ariaal men a copy of Men's Health magazine full of pictures of impossibly well-sculpted men and women. The men looked on with rapt attention and admired the chiseled forms.

"That one, I like," said one nomad who was up in his years, pointing at a photo of a curvy woman who was clearly a regular at the gym.

Another old-timer gazed at the bulging pectoral muscles of a male bodybuilder in the magazine and posed a question that got everybody talking. Was it a man, he asked, or a very, very strong woman?

Copyright 2005The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, International, of Sunday, December 18, 2005.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |