| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted August 9, 2003 |

Professors With a Past |

|

Ed Kashi/Corbis |

| A small but growing number of criminology professors are coming from the ranks of former inmates and asserting that their experience gives them special insight into the criminal justice system. |

By WARREN ST. JOHN |

when Stephen C. Richards, a criminology professor, steps up to the rostrum on the first day of his sociology of corrections classes at Northern Kentucky University, he usually begins his lecture with a confession and a promise.

"I'm an ex-con," Mr. Richards, who served nine years in federal prison for selling marijuana, tells his students. "I'm going to tell some stories and use some profane language. You'll read books that you might not read in other classes. And by the end of the semester, you're going to know more about prisons than you ever imagined."

|

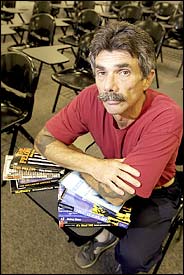

Tim Parker for The New York Times |

| Charles Terryof St. Louis University with books on criminal justice written by former inmates. He is the author of one of them. |

Mr. Richards is a self-described "convict criminologist," one of a small, tightly knit group of ex-convict professors who are shaking up the criminal justice field by challenging some of the academic establishment's assumptions about prisons and inmates. With convictions ranging from selling heroin to armed robbery and even murder, they have tenure-track positions at public universities, attend academic conferences and act as mentors to current convicts who hope some day to join their ranks.

While there have long been isolated ex-convicts keeping a low profile in academia — last month a Pennsylvania State University education professor named Paul Krueger resigned when the university discovered he had spent 12 years in prison after pleading guilty in 1965 to a triple murder — these criminologists are the first group of ex-convict professors to organize into a scholarly movement.

"What's different about the convict criminologists is that they publicly proclaim their ex-offender status," said Francis T. Cullen, a criminal justice professor at the University of Cincinnati. "And they're consciously coming together and arguing that if you systematize their experience, you can come up with a new criminology."

The movement has sparked controversy, not so much because of its members' backgrounds as because of their ideas, which were set forth in a manifesto of sorts published this year, "Convict Criminology," which Mr. Richards edited along with Jeffrey Ian Ross, a professor of criminology at the University of Baltimore (Thomson Wadsworth). The book's thesis is that having spent time in jail, convict criminologists have a better understanding of the criminal justice system than professors who have studied prison from the comfort of their offices. The former inmates engage in research to support their argument that incarceration is overused in the United States — which has a prison population of 2.2 million — and that prison is needlessly dehumanizing.

"Ex-cons make good criminology professors because we know so much about the system," Mr. Richards said. "There are academics who feel somewhat threatened because we're challenging their expertise. Very few venture into prisons, and they never really get it."

The debate about firsthand experience echoes others that have roiled the academy about who is best suited to teach women's studies, Jewish studies and black studies, as well as less contentious discussions about whether published novelists make the best writing teachers, former corporate executives make the best business professors and so on.

| _____________________________ |

| A new academic debate: Does a felony record help criminologists? |

| _____________________________ |

There are around a dozen ex-convict criminology professors around the country; another dozen in the late stages of their graduate school work, soon to become junior faculty members; and still others studying for degrees in prison. Most say they are motivated toward academia by a combination of idealism and practicality: deeply affected by the experience of prison, they share an urge to improve conditions for fellow inmates. And because getting jobs in the private sector is difficult for those with felonies on their records, academia offers at least the chance of a career. "

A lot of convicts want to make use of their time and come out better prepared," said John Irwin, a professor of criminology at San Francisco State University who spent five years in prison for armed robbery. "This couples with the fact that you can never get away from your prison experience."

While a few convict criminologists have histories of violent crime, the majority went to prison in the late 1980's and early 1990's for drug offenses. They came from middle- or upper-middle-class backgrounds and entered prison with high school educations or college degrees.

Daniel S. Murphy, a professor at Appalachian State University in Boone, N.C., is a typical case.

After getting a degree in sociology from the University of Wisconsin and starting a business, he was arrested on a marijuana charge and sentenced to five years in prison in 1994. Two years into his sentence, he said, exasperation with prison life motivated him to start studying in jail for his master's degree in criminology. After getting what he calls his "little Ph.D." — his "prison house diploma" — Mr. Murphy enrolled at Iowa State for graduate school. Mr. Murphy argues that he has an advantage over his mainstream peers.

"I can see both sides of the razor wire," he said.

Criminologists who study prison life engage in ethnography, a branch of anthropology that involves studying alien cultures, in their case, inmate society. They spend long hours inside prisons, conducting interviews.

"If one person tells me there are maggots in the food, it's anecdotal," Mr. Richards said. "If 50 people say there are maggots in the food, we can use it and discuss it."

"Because we know about prison, we know what questions to ask," he continued. "`How many men are in your cell block? Are you double-celled? When we say, `Tell us about the food,' we know about the blue meat and the brown lettuce."

It's this last point that has caused controversy. Many in the field reject the notion that the firsthand experience of prison makes convict criminologists any more qualified to write about the subject, and some even contend that it can be a hindrance. Skeptics say convict criminology can be myopic, focusing exclusively on the injustices of prison life, without considering things like the experience of corrections officers, or the potential benefits of punishment.

"There's a tendency among convict criminologists to say, `Because I've been there, I know and you don't,' " Mr. Cullen of the University of Cincinnati said. "Being there gives you access to some information, but not all the information. It illuminates and it distorts."

As an example, Mr. Cullen referred to evidence that suggests some career criminals may have a genetic disposition that leads to low self-control, and that I.Q.'s among inmates are on average 8 to 10 points lower than the general population.

"Now what convict criminologist is going to say people are in prison because they have low self-control and lower I.Q. scores?" he asked.

But other mainstream scholars say ex-convict criminologists do have an edge. Marianne Fisher-Giorlando, a professor at Grambling State University, said, "They understand one another, and there's some level of trust." As a criminologist who has never actually been incarcerated, she added, "I attempt to understand it, but I never really get there."

Richard R. Bennett, a professor of criminal justice at American University, agrees there can be advantages. "Do you have to be a police officer to study police? No, you don't," he said. "But by being a police officer there's a probability that you'll be able to ask questions that a person who did not have that experience wouldn't be able to. Your experience makes the research much richer."

The convict criminology movement got its start in 1997, at the annual meeting of the American Society of Criminologists. Charles Terry, a recovered heroin addict who spent 12 years in prison for various crimes and who is now a criminology professor at St. Louis University, said he was frustrated by what he saw as a cold, statistical approach by mainstream colleagues. He organized a panel of ex-convict professors to speak candidly about their experience in jail. Mr. Terry, whose arms are covered with prison tattoos of dragons, peacocks and demons, said he sensed his account of prison life made some in the audience uncomfortable. Afterward, though, he received a standing ovation.

In subsequent years, Mr. Terry, along with Mr. Irwin of San Francisco State, organized small panels of ex-convict criminologists at other conferences. The panels were well attended, but even so these criminologists found themselves isolated. When other scholars retired to the bar for cocktails after lectures, the ex-convict criminologists — many of whom are in 12-step recovery programs — stayed to themselves.

"They're probably the most sober group of academics you'll ever meet," Mr. Richards said of his fellow ex-convict criminologists.

Over time the group drew the attention of other ex-convict scholars who had kept quiet about their pasts.

"People came out of the audience — professors and grad students," Mr. Richards said. "And just like at an A.A. meeting, they'd say, `I'm an ex-con.' "

Mr. Richards said he encourages his peers to come clean. "We tell them, `Tell people,' " he said. "In many cases people will be denied opportunities, but that's better than applying, getting the job and having it come out later."

After a few years of attending conferences and telling war stories about prison, Mr. Irwin, the author of several well-known books in the field, including "The Felon" and "The Jail," told his fellow ex-convicts that they had to get to work. "I said no more just standing up and saying `I'm an ex-convict,' " he said. "We've got to do serious research."

The ex-convict criminologists took up Mr. Irwin's challenge. Since getting his doctorate in 1999, Mr. Terry has published two books. Mr. Richards has published 40 articles and is finishing his fifth book.

Mr. Richards said he is now mentoring dozens of ex-convicts who are working on bachelor's degrees — one of the students, an ex-convict who spent 16 years in prison for murder, was recently accepted into graduate school. Mr. Richards said he corresponds with around 50 current inmates interested in going into the field. And he said his group enjoys the support of numerous wardens and corrections officers.

"They're proud of us," he said. "We're alumni of their institutions."

Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Arts & Ideas, of August 9, 2003.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |