| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted March 2, 2003 |

|

Getty Images |

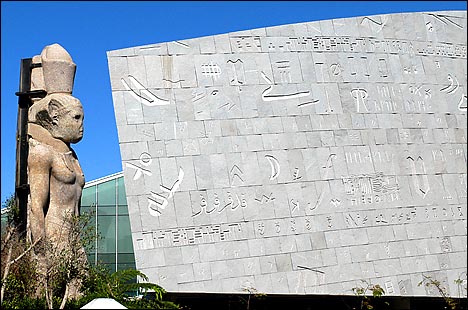

| The Alexandria Library hopes to take up where its legendary forerunner left off a millennium ago. |

Online Library Wants It All, Every Book |

By ROBERT F. WORTH |

The legendary library of Alexandria boasted that it had a copy of virtually every known manuscript in the ancient world. This bibliophile's fantasy in Egypt's largest port city vanished, probably in a fire, more than a thousand years ago. But the dream of collecting every one of the world's books has been revived in a new arena: online.

The directors of the new Alexandria Library, which christened a steel and glass structure with 250,000 books in October, have joined forces with an American artist and software engineers in an ambitious effort to make virtually all of the world's books available at a mouse click. Much as the ancient library nurtured Archimedes and Euclid, the new Web venture also hopes to connect scholars and students around the world.

Of course, many libraries already provide access to hundreds or even thousands of electronic books. But the ambitions of the Alexandria Library appear to surpass those of its rivals. Its directors hope to link the world's other major digital archives and to make the books more accessible than ever with new software.

To its supporters, the project, called the Alexandria Library Scholars Collective, could ultimately revolutionize learning in the developing countries, where libraries are often nonexistent and access to materials is hard to come by. Cheick Diarra, a former NASA engineer and the director of the African Virtual University, said he plans to begin using the Alexandria software this year at the university's 34 campuses in 17 African countries.

Still, the idea faces staggering logistical, legal and technical obstacles: copyright infringement, high costs and language barriers, to name just a few. Its success will depend on its ability to raise money from foundations and to forge links with governments and major universities that can offer access to their own books and materials. At the moment, the project is paid for mainly by the library, which is supported by the Egyptian government and Unesco. Its American founder, Rhonda Roland Shearer, also raised seed money from several private philanthropists, including $800,000 from the philanthropist Paul Mellon, who died in 1999. Its annual operating budget of about $500,000 is more than enough to start the first phase of its online collection, said Ms. Shearer, the American artist who designed the software. She is seeking grants from foundations as well but has no commitments, she said.

An effort so ambitious, though, is likely to require considerable capital as it grows, said David Seaman, the director of the Digital Library Federation. David Wolff, a vice president of production at Fathom, an online learning company owned by Columbia University and other institutions, agrees. "To maintain and grow such an ambitious Web service for a worldwide audience is going to require major infusions of capital," Mr. Wolff said.

The project's creators hope its philanthropic ideals and access to the Islamic world will help raise money. "When people are concerned about violence and fundamentalism, the library is a historical symbol of ecumenism and tolerance and rationality," said Ismail Serageldin, director of the Alexandria Library.

But the Internet venture may also be shadowed by some of the controversies that have plagued the entire library undertaking since it was first conceived three decades ago. Critics have often questioned its cost and asked whether its Enlightenment ideals can survive in a country where censorship is common. And a contribution from Saddam Hussein before the Persian Gulf war hase also raised eyebrows.

Although the library's administrative independence was established by law last year, its paper collection is still small and full of cheap, cast-off paperbacks.

The creators of the new database hope to leave those problems behind by making digital books and scholarly materials more accessible. Users of the Alexandria software will visit the Web site and see a sumptuously illustrated library, with calling cards and stacks, that will link them to online texts much like a standard commercial browser. They will store their digital selections from the library's collection on shelves in an on-screen personal locker.

Online Library Wants It All, Every Book (Page 2 of 2) The software also includes colorful virtual auditoriums, classrooms and offices with lamps where scholars can exchange information, teach classes or hold office hours. The rooms and lecture halls can easily be customized for the universities that choose to use the library's software for remote learning, said Ms. Shearer, whose nonprofit group, the Art Science Research Lab, will run the collective with the library.

Few people have used the software. But Richard Foley, a dean at New York University, said it was more sophisticated and easier to use than Blackboard, a tool to post academic material. "The real trick is not just to post information but to make it usable and interactive," he said. "This is a much less passive approach to information storage, retrieval and transmission."

The library has scanned only about 100,000 pages of its own material, mostly medieval Arabic texts, Mr. Serageldin said. But it has embarked on a plan to digitize thousands of books over the next several years, most of them Arabic texts, with French and English translations, he said. Other works are scheduled to be scanned elsewhere in Africa, including a whole library of crumbling medieval manuscripts in a monastery in Timbuktu in Mali, Mr. Serageldin said. The library will also have access to one million books that are now being scanned by Carnegie Mellon University, which is creating its own vast digital archive and is one of Alexandria's partners. And the library has a vast trove of Web material already donated by the Internet Archive, a California partner with similar universal ambitions. The collective then plans to begin bargaining for access to digital collections at other libraries and universities around the world, offering access to its own materials and its network of scholars in exchange.

Eventually, Ms. Shearer hopes that private companies wanting access to its material will join, helping build revenue for the nonprofit collective and the library.

Not everyone is thrilled by the thought of their works ricocheting around the world free. In the United States, publishers have begun to find ways to seal off access to their copyrighted works. But unlike some for-profit digital libraries that have sprung up in the last decade, the cooperative is interested mostly in books that are already out of copyright, at least at first, said Frederick Mostert, a London lawyer who advises the group on copyright issues. In the meantime, the cooperative plans to begin urging authors to donate their digital rights in the hopes that the courts will let them be used.

Another possible obstacle may arise from the sheer breadth of the project's goals: digital library, lecture hall, international scholars' hub, gateway for ordinary readers and new software package. "It's hard enough to make an offering in any one of those categories," said Mr. Wolff of Fathom. "To combine them all is challenging, particularly in light of the fact that the decision makers in those areas may be different at any given institution."

But Ms. Shearer says the library's large ambitions are also an advantage. The current welter of different approaches to electronic books and resources is a problem for scholars, who will make use of the Web only if it can be made easy. The software she developed, called CyberBook Plus, was designed to allow its use in different formats and languages, with a heavy emphasis on visuals rather than posted text.

And putting everything in one place is no longer as risky as it was in the predigital era, said Brewster Kahle, the founder of the Internet Archive. "One lesson of the original Library of Alexandria," he said, "is don't just have one copy."

Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Arts & Ideas, of March 1, 2003.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |