| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted September 7, 2003 |

Not Molière! Ah, Nothing Is Sacred |

|

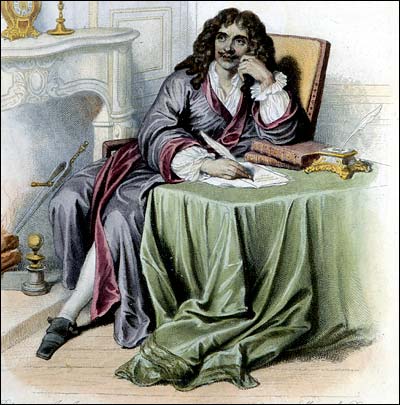

Kharbine-Tapabor Collection |

| Molière, whose masterworks, doubters insist, were actually written by Corneille. |

| By LILA AZAM ZANGANEH |

| TO be or

not to be Molière: that is the latest question wreaking havoc among French academics. In "Corneille in the Shadow of Molière," a book recently published in France, Dominique Labbé, a specialist in what is known as lexical statistics, claims that he has solved a "fascinating scientific enigma" by determining that all of Molière's masterpieces — "Le Tartuffe", "Dom Juan," "Le Misanthrope," "L'Avare" — were in fact the work of Pierre Corneille, the revered tragedian and acclaimed author of "Le Cid." "There is such a powerful convergence of clues that no doubt is possible," Mr. Labbé said. The centerpiece of his supposed discovery is that the vocabularies used in the greatest plays of Molière and two comedies of Corneille bear an uncanny similarity. According to Mr. Labbé, all these plays share 75 percent of their vocabulary, an unusually high percentage. Mr. Labbé's claim has upset more than the insular world of scholars. In the French collective consciousness, Molière is perceived as something of a national Shakespeare. Written in large part for Louis XIV and his court, Molière's comedies instantly became symbols of French culture thanks to their extraordinary dramatic range and extensive popular and scholarly appeal. As Joan Dejean, a professor of 17th-century French literature at the University of Pennsylvania, explained, Mr. Labbé is trying to debunk a national myth. "Molière is the so-called greatest author of the French tradition, so there are significant stakes if you undermine that," Ms. Dejean said. Throughout the wickedly hot French summer, newspaper columnists, television commentators and radio shows have been debating Mr. Labbé's heretical claim. Mr. Labbé isn't the first to call Molière's genius a masquerade. Throughout the 20th century, a French poet named Pierre Louys and several amateur literati made similar allegations drawn from lists of linguistic and biographic concurrences. In the wake of these shaky exercises in literary sleuthing, Mr. Labbé contends he has infallible statistical evidence of Corneille's "fingerprints" all over Molière's greatest works. As early as December 2001, Mr. Labbé published an article on the topic in the Journal of Quantitative Linguistics, which he later developed in "Corneille in the Shadow of Molière." His conclusions are based on a statistical tool called "intertextual distance" and developed by his son, Cyril Labbé, a teacher in applied mathematics who claims to have tested the method on thousands of different texts. This method measures the overall difference in vocabulary between two texts by determining the relative difference in the occurrence of words. Thus, the lower the number, the more likely that the works are from the same author. And the Labbés concluded that — in 16 plays by Molière — the lexical distance with two early comedies by Corneille is sufficiently close to zero to prove that the texts are indeed written by the same hand. They felt especially encouraged in their conclusions by the fact that Molière and Corneille once collaborated publicly on "Psyché," a "comédie-ballet" composed in 1671. According to Mr. Labbé, the motive for a covert collaboration is clear: Corneille wanted money and Molière fame. Immediately, scholars of all stripes reacted vehemently, portraying Mr. Labbé as a charlatan chasing an improbable literary scoop. And Mr. Labbé himself defensively admitted: "I am mostly a statistician and barely a literary critic at all. And I am certainly not a specialist of the 17th century." And that's the problem, said Georges Forestier, an authority at the Sorbonne on 17th-century theater: "Statisticians like Labbé think they have found the ultimate tool to determine authorship, and they use it to aggrandize their position in the field." In his eyes, a strictly scientific approach to authorship is dangerously revisionist, because it omits the textual analysis. "Statistics," Mr. Forestier explained, "should be used only as an auxiliary to complement literary analysis and historical data." Indeed, at the heart of this debate lies a more fundamental question about the use and abuse of scientific tools in the field of letters. Jean-Marie Viprey, a researcher in lexical statistics and literature at the University of Besançon in France, accuses Mr. Labbé of using the veneer of statistical analysis and computer sciences to fool laymen into taking a ludicrous conceit for a groundbreaking discovery. Mr. Viprey takes apart the very principles on which the Labbés have operated.

"Lexical statistics can be useful as an exploratory tool with a descriptive and investigative goal," he said. "In no way can it be used as a proof." In a nutshell, attribution of authorship necessitates a convergence of presumptions. Joseph Rudman, a professor of applied statistics at Carnegie Mellon, agrees that even the best authorship-attribution studies could yield only probabilities. "You can never say definitely, just like in a DNA result," he said. Experts in the period say that Mr. Labbé, for instance, does not take into account the significant constraints in 17th-century literary genres, which induced playwrights to use similar registers of vocabulary and greatly bridled lexical creativity. The stylistic codes at play are therefore far more powerful than the personality of any given writer. And the difference between Corneille and Molière is not so much a matter of lexicon as of syntax and rhythm, nuances that can escape statistical analysis entirely. In fact, Mr. Forestier said, dozens of other 17th-century plays are close in vocabulary to the ones by Molière and Corneille. Mr. Labbé, however, fails to draw any such comparisons, except with a single play by Racine, "Les Plaideurs," considered semantically atypical by specialists. In addition, scholars like Mr. Forestier have presented much historical and philological evidence weighing against Mr. Labbé's conclusions. It is known, for example, that only once in his life was Corneille able to complete two plays in a single year, making it unlikely that he was ever able to write multiple plays in short spans of time. It is known that Molière and Corneille had a long-lasting quarrel that began in 1658, and by that year, Corneille had not written a comedy in more than 14 years. So when they publicly cooperated on "Psyché," in 1671, there seems little reason to believe they had ever collaborated before. Besides, Corneille was extremely pious and in many ways despised the bawdy antics of Molière's comedies. It is also striking to many readers of French classical theater that the two authors' aesthetics are distinct in their forms and themes, in their conception of the comic and the tragic, and even in their finer stylistic turns. Whereas Molière was greatly influenced by the Italian farce, Corneille became increasingly drawn to the heroic genres of the tragi-comique and the tragedy proper. Molière reveled in domestic intrigues, cuckolded husbands and lascivious priests, while Corneille took to historical heroes and high-strung sentiment. Corneille also displayed exceptional attention to obtaining intellectual property rights over his plays, to a degree virtually unknown before. Molière, for his part, kept very strict records of the enormous amounts of money he made, and he, too, fought to retain editorial control of his works. It seems odd, therefore, that two men so unusually scrupulous about their own authorship would willingly leave any ambiguity as to the integrity of their works. In the end, Molière, like Shakespeare, paid a price for not being exclusively an author. Molière was also an actor, and worse, a provincial comedian. Corneille, on the other hand, was a refined tragedian and an aristocratic writer. Fabienne Dumontet, a teacher of French literature at the University of Grenoble, remarks that the three great authors whose paternities are still at stake in contemporary debates — Shakespeare, Molière and Rabelais — are all writers who happened to work on the genre of the farce. "People have a hard time reconciling the idea of high culture and bawdiness, so they tend to identify the author with his work and his characters," Ms. Dumontet said. "Molière has been a victim of his own work." Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Arts & Ideas, of September 6, 2003. |

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |