| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted Novemver 30, 2003 |

| Helping an Old French Art to Rise |

| __________________________________________ |

| It Took an American to Get the Baguette Back on Track |

|

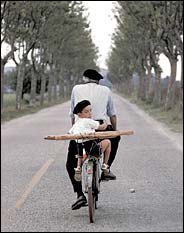

Elliott Erwitt/Magnum Photos |

| By DEBORAH BALDWIN |

PARIS — Steven L. Kaplan stared through the window of a Paris bakery one Sunday morning, looking like an osprey ready to swoop.

"I've watched him work," Mr. Kaplan said hungrily, speaking of the baker, Dominique Saibron, and his tenderly cultivated sourdough starter, known in the business as levain.

If Mr. Kaplan admires your levain, it is no small thing. He knows more about French bread than practically anyone else, some of France's top bakers say.

A relentless researcher, Mr. Kaplan was one of the people who helped salvage the crusty mainstay in the 1980's, when many baguettes tasted like sliced white bread.

Mr. Kaplan has, in fact, done so much to ennoble the baguette and its cousins, the boule and the bâtard, that he has twice been dubbed a chevalier by the French government for his contributions to the "sustenance and nourishment" of French culture.

The bread baron Francis Holder, who runs Paul, the innovative international chain of bakeries, calls Dr. Kaplan's expertise extraordinary. Jean Lapoujade, a director of the renowned bakery Poilâne, said, "We look forward to his next work with impatience."

| _______________ |

Once again the yeast has time to do its job, and perhaps the baker is happier as well. |

| _______________ |

Not bad when you consider that Mr. Kaplan, 60, is not a baker and not even French. He is an American professor at Cornell University who grew up in Brooklyn and Queens. "We ate kornbrot," he said, speaking of the dense European rye.

Mr. Kaplan's tart put-downs and crisp observations suggest he might have been French in a previous life. And to the French, who tend to revere intellectuals more than their American counterparts do, Mr. Kaplan has become something of a celebrity. In the late 1990's, an elite bakery like Poujauran would have a copy of his heavily footnoted, 740-page treatise, "Le Meilleur Pain du Monde: Les Boulangers de Paris au XVIIIe Siècle" (Fayard, 1996), or "The Best Bread in the World: The Bakers of Paris in the 18th Century," nestled next to the croissants. He speaks in fluent French sound bites, making him an ideal talk-show guest. You could turn on the television or radio or open Le Monde, and there he was, weighing in on what he called insipid baguettes.

In his award-winning books and many papers on the cultural and political significance of French bread, Mr. Kaplan has charted its role in the revolution of 1789, its anchoring of the French table through the early 20th century and its decline during the 50's, when the baguette became a voluptuous but empty emblem of postwar prosperity. A victim of hypermechanization, fast-acting industrial yeast and suppressed fermentation, Mr. Kaplan said, "it looked lovely but was barren of odor and taste."

Scholars say Mr. Kaplan was the first person to put a shift in consumer tastes into the context of a changing workplace and society.

Mr. Kaplan is "a superb craftsman, someone working on an important subject and doing justice to it," said Robert Darnton, a Princeton historian who specializes in 17th and 18th century France. "The subject of bread is far more crucial than most modern people appreciate: bread really was the staff of life in early modern Europe, and it deserves such a good historian."

|

| Ed Alcock for The New York Times |

| Steven L. Kaplan, right, praises the sourdough starter of Dominique Saibron. Mr. Kaplan teaches European history at Cornell University. |

Roger Chartier, a French cultural historian and visiting professor at the University of Pennsylvania, said, "He has a very profound, deep knowledge of the archives."

And Gérard Brochoire, head of the National Institute for Bread and Pastry in Rouen, France, praised the "large documentary richness" of Mr. Kaplan's research, the fruit of a 20-year odyssey to some 58 French archives, where primary documents had rarely been touched by French historians. He characterized Mr. Kaplan's description of the complex grain and flour trade as ground-breaking, saying that in a closed business associated for centuries with suspicion and corruption, Mr. Kaplan "benefits from being an outsider."

In his 2002 book, "The Return of Good Bread," Mr. Kaplan tells how a new generation of bakers took up the slow-fermentation cause in the 90's, slashing the amount of yeast and shutting down the heavy equipment. Today temperature-controlled fermentation chambers give the dough not only a whole night to develop some depth but also an opportunity for the baker, as Mr. Kaplan puts it, "to sleep with his wife."

Slightly built (for a man who says he has tasted the wares at some 600 Paris bakeries), with oversize glasses and a small gray beard, Mr. Kaplan says his fascination with French food started when he was 19 and took a job in a wine-bottling plant in Paris, partly as a diversion from the unexpected and traumatic death of his father, a lawyer with leftist leanings.

| _______________ |

| The loaf's 'sybolic hegemony' had to be written down before it seemed real. |

| _______________ |

After graduating from Princeton, Mr. Kaplan toyed with law school. "I was going to avenge his relative lack of success," he said. "I was going to be a rich lawyer."

Then he came to France as a Fulbright scholar, studying the revolution.

"There was no more political question than bread," he explained. "Political legitimacy is grounded in having a sufficient quantity of bread at affordable prices."

It was probably only a coincidence that this item of "symbolic hegemony," as he calls it, was also good to eat.

No French historian had taken bread so seriously, he said: "The very banality may have impeded it, and it was not archivally easy because documents were scattered and hard to master."

Gérard Allemandou, a restaurateur and cognac expert, said that Mr. Kaplan's analysis of the role of the humble loaf in French history and culture had changed the way he looked at himself as a French citizen and as a chef who works with commonplace ingredients.

"Culture isn't culture until it is written down," Mr. Allemandou said. "People think they know bread because they are French. But I didn't understand." Choosing his words carefully, he added that Mr. Kaplan's nationality was "a bit of a pity."

As a graduate student, Mr. Kaplan realized he had to learn how bread is made and became an apprentice at a Paris bakery. Using the phrase for "get your hands in the dough," he said, "That gave me a vocabulary and enabled me to `mettre la main à la pâte,' and that's when I began to taste."

Mr. Kaplan clearly has a passion. He nearly missed the birth of his son in 1969 because he was steeped in conversation with the late Pierre Poilâne, founder of the bakery.

Mr. Kaplan teaches European history at Cornell, where his most popular class is on the history of French food.

He is often holed up in snowy Ithaca for the winter — claiming that he eats no bread because it's no good — while spending increasingly long summers in Paris, where he and his French wife share an apartment.

He is finishing work on a guidebook devoted to sifting out the finest Paris bakeries (there are 1,273 to choose from).

He is also delving into the story of a small town in southern France where contaminated bread drove people mad in 1951.

For now, baguette revivalists — spurred in part by Mr. Kaplan's notion of bread as the epitome of both French history and culture — draw from him moral strength and culinary rigor.

"I reminded them of how and why to be passionate about bread, once a matter of life and death and a powerful social and political marker, now an object of pleasure more than necessity but still highly charged symbolically," Mr. Kaplan wrote in a recent e-mail exchange. "They trust me, confide in me and count on me to make demands on them so that the commitment to quality will not wane."

Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company. Remember from The New York Times, Arts & Ideas, of November 29, 2003.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |