|

|

| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted January 8, 2008 |

Four Wheels for the Masses: The $2,500 Car |

|

|

|

PARANJPE/REUTERS |

|

| India's Tata Group Chairman, Ratan Tata. Tata Group sees overseas revenues rising to more than 60 percent of its total earnings in 2007/08 from 38 percent a year earlier. |

By ANAND GIRIDHARADAS |

MUMBAI, India — What does it take to build the world’s cheapest car? omments Do you think a $2,500 car will change what people drive?

For Tata Motors of India, which will introduce its ultra-cheap car on Thursday, the better question was, what could it take out?

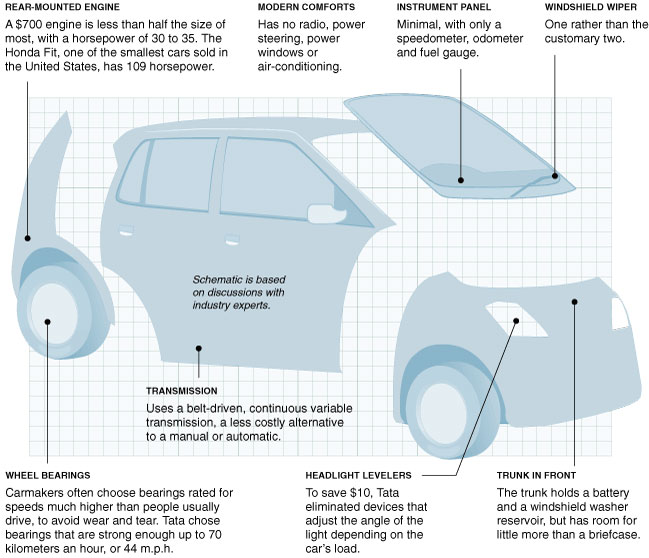

The company has kept its new vehicle under wraps, but interviews with suppliers and others involved in its construction reveal some of its cost-cutting engineering secrets — including a hollowed out steering-wheel shaft, a trunk with space for a briefcase and a rear-mounted engine not much more powerful than a high-end riding mower.

The upside is a car expected to retail for as little as the equivalent of $2,500, or about the price of the optional DVD player on the Lexus LX 470 sport utility vehicle.

The downside is a car that would most likely fail emission and safety standards on any Western road, and, perhaps, in India in a few years, when the country imposes tougher environmental standards.

|

But Tata is not looking to ply California’s highways. Instead, the company wants to provide four-wheel transportation for the first time to people accustomed to getting around on two, including hundreds of millions of Indians and others in the developing world.

Even so, the “People’s Car” (a nickname, since Tata has kept the real name under wraps, too) may ultimately affect what many people drive around the world, since it is part of a broader trend among carmakers to try to build less expensive cars.

“It’s basically throwing out everything the auto industry had thought about cost structures in the past and taking out a clean sheet of paper and asking, ‘What’s possible?’” said Daryl T. Rolley, head of North American and Asian operations for Ariba, which helps supply parts to Tata, BMW, Toyota and other carmakers. “In the next five to 10 years, the whole auto industry is going to be flipped upside down.”

The French-Japanese alliance Renault-Nissan and the Indian-Japanese joint venture Maruti Suzuki are trying to figure out how to make ultra-cheap cars for India. And struggling Western automakers are looking to see where the cost-obsessed ethos of the developing world can help their bottom line. In the most recent example, Ford was expected to announce Tuesday that it would make India its manufacturing hub for low-cost cars.

Some analysts are predicting that just as the Japanese popularized kanban (just in time) and kaizen (continuous improvement), Indians could export a kind of “Gandhian engineering,” combining irreverence for conventional ways of thinking with a frugality born of scarcity. Or, as Indian auto executive Ashok K. Taneja describes the philosophy, “When I need silver, why am I investing in gold?”

Some of the few people who have seen the car describe a tiny, charming, four-door, five-seater hatchback shaped like a jelly bean, small in the front and broad in the back, the better to reduce wind resistance and permit a cheaper engine. “It’s a nice car — cute,” said A. K. Chaturvedi, senior vice president of business development at Lumax Industries, a supplier in Delhi that developed the car’s headlights and interior lamps.

Driving the cost-cutting were Tata’s engineers, who in an earlier project questioned whether their trucks really needed all four brake pads or could make do with three. As they built Tata’s new car, for about half the price of the next-cheapest Indian alternative, their guiding philosophy was: Do we really need that?

|

TOMAS MUNITA FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES |

| The four-door Tata Nano is only a little over 10 feet long and nearly 5 feet wide. It has a two-cylinder engine in the rear. |

The model appearing on Thursday has no radio, no power steering, no power windows, no air-conditioning and one windshield wiper instead of two, according to suppliers and Tata’s own statements. Bucking prevailing habits, the car lacks a tachometer and uses an analog rather than digital speedometer, according to Mr. Taneja, who until recently was president of the Automotive Component Manufacturers Association of India, representing many of Tata’s suppliers as they signed deals with the company.

Frugal engineering pervades the car’s internal machinery, too, with even greater implications for the vehicle’s safety and longevity.

To save $10, Tata engineers redesigned the suspension to eliminate actuators in the headlights, the levelers that adjust the angle of the beam depending on how the car is loaded, according to Mr. Chaturvedi of Lumax. In lieu of the solid steel beam that typically connects steering wheels to axles, one supplier, Sona Koyo Steering Systems, used a hollow tube, said Kiran Deshmukh, the chief operating officer of the company, which is based in Delhi.

Tata chose wheel bearings that are strong enough to drive the car up to 45 miles an hour, but they will wear quickly above that speed, reducing the car’s life span but not threatening consumer safety, according to Mr. Taneja. The car’s top speed is 75 miles an hour.

Reducing the weight curbed material costs and enabled the company to use a cheaper engine. People familiar with the car describe a $700 rear-mounted engine built by the German company Bosch, measuring 600 to 660 cubic centimeters, with a horsepower in the range of 30 to 35. By comparison, the Honda Fit, one of the smallest cars available in the United States, has a horsepower of 109.

According to industry experts, the car runs on a continuous variable transmission, a lighter alternative to manual or automatic transmissions.

Though it was never popular in the United States because of its often sluggish acceleration, continuous transmission was once widespread in Europe and has resurfaced in the United States in vehicles like the Nissan Murano S.U.V. and the Toyota Prius.

While Tata reverted to old technologies in places — Leonardo da Vinci conceived an elegant precursor to the continuous transmission in the 15th century — it embraced cutting-edge sourcing practices, said Mr. Rolley at Ariba, which has assisted both Tata and its foreign rivals in buying parts.

Traditionally, carmakers cultivated long-term relationships with suppliers, but companies have gradually embraced electronic sourcing, using Internet auctions that force suppliers to compete for business. But even the most efficient carmakers buy no more than 10 percent to 15 percent of parts electronically, Mr. Rolley said. Tata sources 30 percent to 40 percent that way.

Critics of the Tata car have asked how a car that prunes thousands of dollars off regular prices can possibly comply with safety and environmental norms. The answer may be that the car comes at a particular moment in India’s development, when the country is affluent enough to support strong demand for automobiles but still less regulated than developed countries.

Tata officials say the car will comply with all Indian norms. But they are changing. India’s major cities plan to adopt the Euro IV emissions standard in April 2010, requiring a 35-fold reduction in sulfur emissions over the current Euro III standard, according to Anumita Roychowdhury of the Center for Science and Environment in New Delhi.

New safety rules mandating air bags, antilock brakes and full-body crash tests are also coming, Ms. Roychowdhury said.

She said it was unlikely the car would be able to keep its populist price tag once those regulations take effect.

And the car may be less environmentally friendly than it claims. Unlike cars in the United States, Indian vehicles do not have to come in for regular inspections after they are on real roads, which often batter the systems that curb emissions.

Michael Walsh, a pollution consultant and former United States Environmental Protection Agency regulator, said that a car so cheap was likely to lack the complex technology to maintain its initial level of emissions and that without such technology cars could soon be producing four to five times their initial pollution level.

“It strikes me as impossible that such a vehicle will be a very clean vehicle over the life of the vehicle,” Mr. Walsh said.

In a recent interview, Ratan Tata, chairman of the Tata Group, also suggested that the car’s lightness, while favorable for the environment, had frustrated efforts to make it safe. “We will have far lower emissions than today’s low-end cars,” he said. But, he added, “the emissions standards were much easier to meet than the crash test.”

In most American cars, safety features alone cost more than $2,500, said Adrian Lund, president of the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety in Arlington, Va. But, he added, “if what we’re talking about in India is people having the option of getting off the streets, from motorcycles and bicycles where they are at risk from bigger vehicles, this may actually be an improvement of the safety environment.”

Even if the Tata car never drives on Western roads, the philosophy behind it will influence global car makers, Mr. Rolley of Ariba said.

Manufacturers are searching for ways to make small cars for the middle class in India and China; to produce small cars for their own markets, hurt by rising gas prices; and to improve the profit of existing larger cars. Tata’s car would be mined for applicable lessons, Mr. Rolley said, predicting that more would be designed with cost in mind.

In one past example, after Renault-Nissan began making cheap cars in Romania, it transferred low-cost engineering techniques to its plants producing more expensive models — for example, making doors flatter so they could be stacked in greater volume in shipping containers, according to Pauline Kee, a Nissan spokeswoman.

Consumers in wealthy nations can perhaps expect more hollow steering shafts, actuator-free headlights and tiny trunks.

“This will be no different,” Mr. Rolley said, “from when U.S. companies spent a whole decade in the ’80s thinking about what Japanese management techniques they had to adopt.”

Copyright 2008 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Business, of Tuesday, January 8, 2008.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |