| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted July 6, 2006 |

| Aristide: Drugs, grand thievery, brutal murders, and millions of dollars |

| Miami Herald Watchdog |

| Drug Probe Targets Aristide |

| By JAY WEAVER AND JACQUELINE CHARLES, MIAMI HERALD WRITERS |

| jjweaver@MiamiHerald.com |

• This is the first of two parts.

|

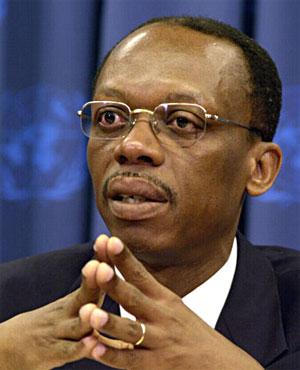

Miami Herald File Photo |

Jean-Bertrand Aristide was a modern-day Moses to Haiti's poor masses, a former Catholic priest who rose to the presidency by promising to wash away the country's bloody and corrupt past. But since his ouster as president in 2004, U.S. authorities have been investigating detailed accounts alleging that Aristide and several top aides sought and took millions of dollars in bribes from drug traffickers in Haiti, The Miami Herald has learned.

So far, a federal grand jury probe in Miami has led to 22 convictions of mostly Haitian drug traffickers, ex-police officers and a high-ranking politician close to Aristide. Although the exiled former president is a main target of the ongoing investigation, he has not been charged.

The allegations against the ex-president come from numerous sources, but the evidence has not risen to a level to press a case against Aristide, say U.S. law enforcement officials, who have been hampered by a lack of financial records.

Still, The Miami Herald has learned from interviews with about 20 law enforcement officials, defense lawyers and others involved in the case that Aristide has been accused of being at the center of his country's narco-trafficking and money-laundering activities from 2001 to 2004.

Authorities have gathered evidence, including testimony by cooperating defendants convicted in the case, alleging that:

• Soon after he took office in early 2001, Aristide held a meeting at his Port-au-Prince home with his presidential security chief, two government security advisors, the national police chief and a district commander to organize a scheme to shake down Colombian and Haitian drug smugglers for kickbacks for both his personal and political activities.

• Drug traffickers bribed Aristide to turn a blind eye to shipments of Colombian cocaine through Haiti, directly paying him hundreds of thousands of dollars in cash during regular visits to his home.

• Convicted drug kingpin Beaudouin ''Jacques'' Ketant personally delivered $500,000 a month in a suitcase to Aristide's home, he told authorities. He said the suitcase had a combination lock set to 7-7-7 at Aristide's request because that was his favorite number.

• Traffickers gave Aristide $200,000 to buy a helicopter in 2002, but the president pocketed the money and instead used government funds to rent a helicopter from Miami-based Biscayne Helicopters. Those same traffickers also bought a $75,000 ambulance in Miami that was shipped to Haiti for the president's private charitable Aristide Foundation.

• Traffickers spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on carnival festivities in February 2002 that were arranged by the Aristide government. They also paid for some of Aristide's July birthday celebrations, his Lavalas Family Party and his foundation.

• At Aristide's direction, some of the traffickers' bribes helped buy weapons smuggled into Haiti to equip national police officers as well as pro-Aristide street gangs that harassed his opponents during his second term as president, between 2001 and 2004, according to former Haitian law enforcement officials and drug traffickers who are cooperating with U.S. investigators.

ACCUSERS CALLED `LIARS'

Lawyer for Aristide calls accusations `inconceivable'

Aristide's longtime lawyer, Ira Kurzban, said he does not believe the allegations against the former president.

Speaking generally, Kurzban said that the federal prosecution is politically motivated and that the U.S. government's witnesses are ''liars'' seeking to reduce their prison sentences by fingering the former president in their money-laundering and cocaine enterprise.

''It is inconceivable to me that Aristide would do anything for personal gain,'' Kurzban said, commenting on the ex-president's character. ``He was not a person interested in money.''

So far the U.S. investigation has been built on testimony from many of the 22 mostly Haitian cocaine smugglers, police officers and others convicted in Miami in the past 2 ˝ years. The probe, spearheaded by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) with help from the Internal Revenue Service, has focused on cocaine smuggling during Aristide's second presidential term.

The investigation continues as the Haitian government carries out its own separate inquiry into the Aristide administration and foundation records, so far concluding that the president had looted government coffers, Haitian government records show. The interim government that replaced Aristide two years ago filed suit in Miami last year to recover ''tens of millions of dollars'' allegedly stolen by the former president and others from Haiti's treasury and its phone company. Neither the Haitian investigation nor the civil suit alleges drug trafficking.

To this day, the 52-year-old Aristide remains intensely popular in Haiti and has expressed a desire to return home from exile in South Africa after the recent election of President René Préval, once an Aristide ally. That would upset Haiti's domestic politics and Préval's relations with the U.S. and French governments, which regard Aristide as a destabilizing factor in Haiti.

CLAIMS UNSUPPORTED

Probers report absence of incriminating records

While several witnesses have testified against the former president in the U.S. drug-trafficking probe, investigators have told The Miami Herald that they have yet to uncover bank records and other financial statements that support the claims. The absence of such documents to solidify their case against Aristide has prevented authorities from seeking a federal indictment in Miami, U.S. law enforcement officials said.

Efforts to reach Aristide for comment on this story failed. Kurzban, who represented the Haitian government as its lawyer from 1991 to 2004, said he did not believe that the ex-president would agree to an interview.

Kurzban, who still speaks on Aristide's behalf, said that while people in Haiti were well aware of the country's drug-trafficking problem, it came as a ''shock'' to him when he learned that Aristide and others in his government became targets of a U.S. criminal investigation.

He said that, if anything, Aristide cooperated with the federal government in the crackdown on cocaine smuggling in 2003, including allowing Ketant to be turned over to U.S. authorities. He said that money donated to the Aristide Foundation went to the poor for relief programs such as rice subsidies.

Haiti, an impoverished country where cash and corruption go hand in hand, has long been a significant transit point for Colombian cocaine headed for U.S. streets. From there, it sometimes is smuggled directly to the United States. Another route: from Haiti to the Dominican Republic, west to Puerto Rico and then to the U.S. mainland.

During Aristide's second term as president, an estimated 10 percent of all cocaine smuggled into the United States flowed through the Caribbean corridor, especially Haiti, according to a 2006 federal report by the National Drug Intelligence Center.

Shortly after the Aristide government turned over Ketant to U.S. officials, the U.S. government broadened its drug investigation by looking into the Aristide leadership.

It was during a 2004 sentencing in federal court in Miami that Ketant accused Aristide of turning Haiti into a ''narco-country'' and being a ''drug lord.'' Not under oath at the time, Ketant was sentenced to 27 years in prison and ordered to pay $30 million in fines and forfeitures.

Behind the scenes, he began to cooperate as a key witness for prosecutors, providing details on his alleged payoffs to Aristide and others in exchange for a free hand to ship cocaine through Haiti to the United States. His testimony triggered some of the indictments against the 21 others on money-laundering or cocaine-smuggling charges, U.S. law enforcement officials said.

Another major witness was Aristide's former security chief, Oriel Jean, who was convicted last year in a separate federal case of money-laundering and sentenced to three years. He fingered the same drug traffickers, police officials and politicians -- including Aristide.

And during his testimony at two Miami trials last year, he linked Aristide to at least two people implicated in Haiti's drug trade and the U.S. investigation.

In sworn testimony at those trials, Jean said he was introduced in late 2001 or early 2002 to one drug lord, Serge Edouard, by Hermione Leonard, then the director of the national police's Port-au-Prince district and a woman who was close to Aristide.

''She told me that the president is aware that she has contacts'' with major drug traffickers, he testified at Edouard's trial, without elaborating. Leonard, wanted by the DEA, is believed to be hiding in the Dominican Republic.

Jean also testified at trial that he and Aristide approved a national security ID card for Edouard in 2002. He testified that the security badge allowed Edouard to travel throughout Haiti without being stopped by police. Edouard was convicted in that trial on drug charges and is serving a life sentence.

Defense attorneys for Ketant and Jean declined Miami Herald requests to interview their clients.

Ketant also has told authorities that among other drug traffickers who paid off Aristide and members of his inner circle were Ketant's brother, Hector, and Gilbert Horacious, according to sources familiar with the case. Ketant said Horacious was a longtime friend of Aristide's who introduced him and other traffickers to the Haitian president, according to sources familiar with the case.

Ketant's brother was fatally shot in Haiti in 2003, and Horacious was gunned down last year in the Dominican Republic. Shortly after Aristide fled the country on Feb. 29, 2004, hundreds of thousands of dollars in rotted $100 bills were found hidden in his home, according to U.S. news reports. U.S. federal investigators analyzed some of the bills but could not figure out where the money had come from.

ASSOCIATES ACCUSED

Several are alleged to have laundered money

While investigators have struggled to piece together a paper trail leading directly to the former president, they have identified several people in his government who allegedly helped launder drug money for him.

The Miami Herald has learned that the Ketant brothers and other major traffickers made cash contributions to the Aristide Foundation through one of its high-ranking members.

According to traffickers and U.S. law enforcement officials, Aristide allegedly ordered Port-au-Prince district police chief Leonard to pass any seized drugs on to Edouard and other Haitian traffickers for resale. The smugglers, in turn, donated some of the tainted proceeds to the Lavalas party or the foundation, they said.

Aristide also instructed Haitian Sen. Fourel Célestin, who represented the Jacmel area southwest of the capital, to solicit donations from drug traffickers for Lavalas, according to convicted drug smugglers, ex-police officers and U.S. law enforcement officials.

Convicted last year after a plea deal with Miami prosecutors, Célestin admitted taking a $200,000 bribe to help secure the release of two detained Colombian traffickers. Célestin is now cooperating with prosecutors.

Under federal law, prosecutors would not have to prove that Aristide was personally involved in moving loads of cocaine to the United States -- only that he allowed traffickers to use his country and received kickbacks in return. If Aristide comes under a U.S. indictment, the threat of extradition to the United States might keep him from pushing to return to Haiti, according to legal observers. It may also keep Préval from worrying too much about the prospect of his former mentor's return.

After February's presidential election, Préval said that Aristide, like all Haitians, could legally come home. But he added a cautionary note, saying Aristide ''must decide whether he wants to return, if there are legal and other actions'' pending against him.

NEXT, principal related page: A two-year-old corruption investigation of former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide is stalled in Haiti, with millions of dollars in blocked funds gone from Haitian banks.

Reprinted from The Miami Herald of Sunday, July 2, 2006.

Related text: Putting former Haitian murderous dictator Aristide in tight handcuffs, whose job is that?

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |