| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

More Special Reports |

| Posted September 25, 2005 |

Don't Blink. You'll Miss the 258th-Richest American. |

| Inside |

|

Money Trials |

| _______________ |

Nina Munk |

SEPTEMBER 25, 2005 THE latest Forbes 400 list of the richest people in America has just hit the newsstands. The idea for the Forbes 400 - rather than, say, 300 or 500 - was inspired by Mrs. Astor's 400, the definitive list of New York high society in the 1890's. It's rumored that Mrs. William Backhouse Astor Jr. limited her social list to 400 because only 400 people could fit into her ballroom, but that may not be true. In any case, they had to be the right 400 people. As her escort, Ward McAlister, explained to reporters in 1888: "If you go outside that number, you strike people who are either not at ease in a ballroom or else make others not at ease."

The first edition of the Forbes 400, dated Sept. 13, 1982, included mainline families like the Rockefellers, the Mellons and the du Ponts. But they found themselves together with self-made men, some of whom were not terribly at ease in a ballroom: William R. Hewlett, who had started Hewlett-Packard in a one-car garage with his classmate David Packard and was then worth $1.3 billion; Robert C. Guccione, the founder of Penthouse magazine, then worth $400 million; Saul P. Steinberg, a corporate raider who had accumulated a $260 million fortune; An Wang, originally of Shanghai, who had started Wang Labs with $15,000 in 1951 and was worth around $400 million in 1982; Meyer Lansky, a mobster whose estimated net worth that year was $200 million; and Laurence A. Tisch, who built a fortune then valued at $600 million by assembling a huge conglomerate, the Loews Corporation. (Note: all net worth figures are in 2005 dollars.) All you needed to join the Forbes 400 list was money.

|

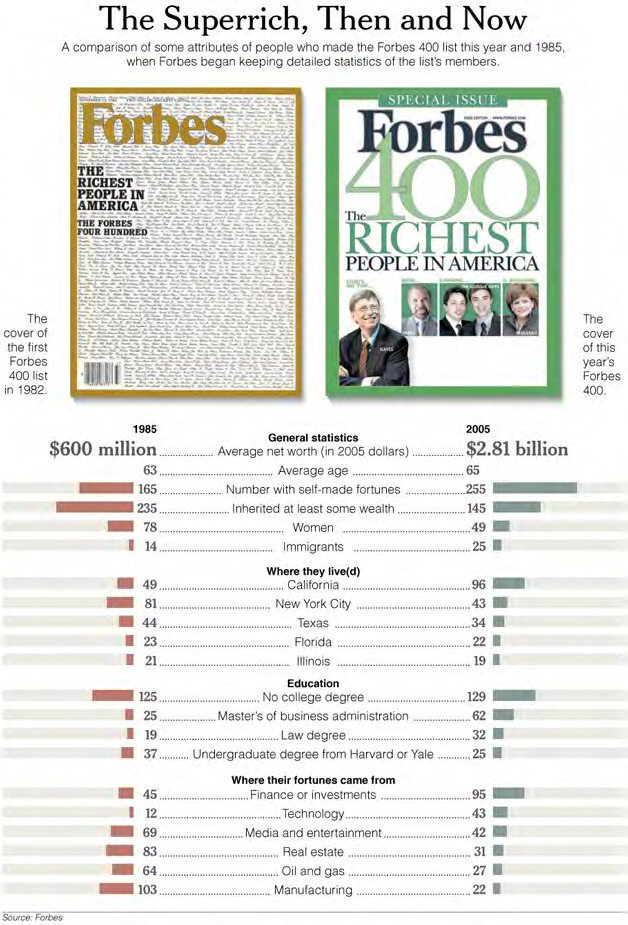

Right from the start, the Forbes 400 reflected an American ideal: we were a nation of smart, hardworking, resourceful, determined, innovative, daring self-starters. Above all, the Forbes 400 suggested mobility and unlimited opportunity. Every year, more of the old names fell off the list, only to be replaced by names you'd never heard of - names of people who had been inspired to build something from nothing. Inherited wealth, which once dominated the Forbes 400, has over the years come to account for less than 40 percent of the list. The number of Ivy League graduates has dropped, too. And New York City is no longer the epicenter of American wealth.

A few days ago, I read through the newest Forbes 400 list of the richest people in America, hoping to find many names I'd never heard of. They're not there. Through no fault of its own, the list no longer reflects a dynamic and elastic economy; instead, it reflects a growing concentration of wealth and economic power. Warren E. Buffett, Paul G. Allen, Kirk Kerkorian, John W. Kluge, Carl C. Icahn, Michael R. Bloomberg, Ronald O. Perelman, Leona Helmsley, Henry R. Kravis, the Waltons, the Pritzkers, the Newhouses, the Lauders - the same old names, one after another.

It's hard to say when the Forbes 400 list started to stagnate, but 1999 may have been a turning point. That was the year when Bill Gates's estimated net worth hit $100 billion. So quickly had his fortune grown that over the previous 12 months, according to Forbes's calculations, Mr. Gates had made himself another $1 billion every eight days.

Mr. Gates, who has held the No. 1 position on the list continuously since 1994, is an extreme example of accumulated and self-generating wealth, but he's part of a trend. Twenty years ago, there were 14 American billionaires on the Forbes 400. Today, the list includes 374 (known) billionaires. In 1985, the combined wealth of the Forbes 400 was $238 billion, adjusted for inflation. Today, the 400 richest people in America are together worth $1.13 trillion. To put that number in perspective, $1.13 trillion is more than the gross domestic product of Canada. And it is more than the G.D.P. of Switzerland, Poland, Norway and Greece - combined.

The median household income of Americans has been stuck at around $44,000 for five years now. The poverty rate is up. Members of the Forbes 400, meanwhile, are richer than Croesus, and every hour they are getting richer.

Lawrence J. Ellison, founder of Oracle, whose net worth has swollen to $17 billion from $4.2 billion in the last 10 years, is profiled in the latest issue of Vanity Fair alongside his new $300 million, 454-foot yacht. ("It's really only the size of a very large house," he remarked off-handedly.) In Manhattan, where the disparity between rich and poor is now greater than in any other part of the country, Rupert Murdoch (net worth: $6.7 billion) has bought the penthouse at 834 Fifth Avenue for $44 million, all cash. The hedge fund manager Steven Cohen (net worth: $2.5 billion) recently paid $52 million for a drip painting by Jackson Pollock.

Making my way down the latest list, through the names of billionaires worth two or three times what they were just a few years ago, I felt a sudden nostalgia for the old Forbes 400 and the promise it held out. Then an unfamiliar name caught my eye: Brad M. Kelley. Who is Brad M. Kelley, America's 258th-richest person?

According to Forbes, Mr. Kelley is 48 and worth $1.3 billion. I Googled him. Nothing, or at least nothing substantial. I ran a LexisNexis search, only to discover that, until now, Mr. Kelley had for the most part been overlooked by the news media.

I called him at home. (His number is listed.) Mr. Kelley was not at all glad to hear from me. At one point, frustrated by my questions, he blurted that he felt he was on some sort of reality show: "I'm trying to, you know, my purpose in talking to you is not so much being courteous, which I try to be, it's damage control and it's really uncomfortable for me and I really wish you'd avoid as much personal matter as possible," he said.

The truth is, if you buy up 1.25 million acres of ranching land across southwestern Texas, Florida, and parts of New Mexico, as Mr. Kelley has done recently, you can't escape attention forever. If you proceed to dedicate parcels of that land to wildlife conservation, as Mr. Kelley has also done, you're practically crying out to be noticed. Eventually someone like Mr. Kelley, who's spending millions of dollars conserving black rhinos, white rhinos, pygmy hippos, okapi, anoas, impalas, white-bearded wildebeests, Nile lechwe, Eastern bongos and Beisa oryx is going to be the subject of an article in The New York Times.

Mr. Kelley is not what we've come to expect of Forbes 400 billionaires. For one thing, he's never been on a yacht. He drives a white Ford pickup and is the only member of the Forbes 400 from Kentucky - though he recently moved to Tennessee to be near his children's school. Mr. Kelley and his wife, Susan, have been married for nearly 20 years. He did not go to college. "I guess I just don't find that as unusual or remarkable as apparently a lot of other people do," he told me. "I mean, I've had a lot of M.B.A.'s that've worked for me over time, off and on, that, excuse my French, were useless as teats on a boar hog."

Born and raised in Franklin, Ky., a small town (population 8,000) about 40 miles north of Nashville, Mr. Kelley seemed most likely to take over his family's farm. According to the Franklin-Simpson High School yearbook of 1974, the year he graduated, Mr. Kelley was not an athlete. Nor was he especially handsome. He was secretary for the Future Farmers of America, winner of the Courier-Journal Louisville Times Future Farmers of America contest and a member of the Who's Who Among American High School Students. As well, he was named Corn Derby winner.

Here's the business story: In 1991, when few wanted to be anywhere near the tobacco business, Mr. Kelley started a cigarette company from scratch. Called Commonwealth Brands, and established with a handful of employees in Bowling Green, Ky., it set out to undercut the big tobacco companies by producing discount "branded generic" cigarettes. In 2001, just 10 years after starting the company, Mr. Kelley sold Commonwealth to Houchens Industries for $1 billion in cash. By then, Commonwealth Brands was the fifth-largest cigarette maker in the country, with sales approaching $800 million. Its top brand, USA Gold, was, and still is, the nation's eighth-best-selling cigarette.

Asked for the secret to his success, Mr. Kelley replied: "I like to think it was discipline and patience and avoiding pitfalls and working for the long term - a whole lot of corny things that'll make me come off looking like an idiot in your article," he answered, before adding quickly: "I'm sure as heck not Horatio Alger. There are a lot of people out there who are real smart and work real hard, and it doesn't happen for them. I just happened to be the one that it did. Sometimes you get dealt a good hand."

When we were done, I said to Mr. Kelley, "You know, you may need an unlisted phone number after this."

There was a pause.

Then he said: "You think so?"

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Sunday Business, of Sunday, September 25, 2005.

*Related article: Richest are leaving even the rich far behind

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |