| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| More Books and Arts |

| Posted August 23, 2010 |

|

Crime (Sex) and Punishment (Stoning) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MARKUS SCHREIBER/ASSOCIATED PRESS |

|

| Outrage An Iranian woman sentence of stoning, given to a woman accused of adultery, led to protests like this one in Berlin. Iran then redefined her-crime as murder. |

|

By ROBERT F. WORTH |

|

|

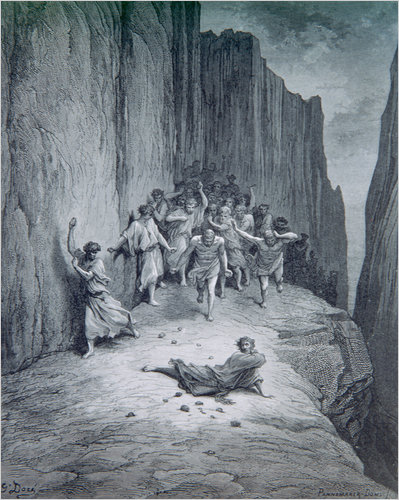

CORBIS |

| Literary Execution An engraving by French printmaker Gustave Doré of the stoning of St. Stephen, then published in Dante's "Purgatory" in 1868. |

| _______________________________ | |

|

|

|

| An act that seemed to violate the community's identity called for a communal response. | |

| _______________________________ |

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |