| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

More Special Reports |

| Posted March 7, 2006 |

| The Real Estate Issue |

|

Photographs by Michael Edwards |

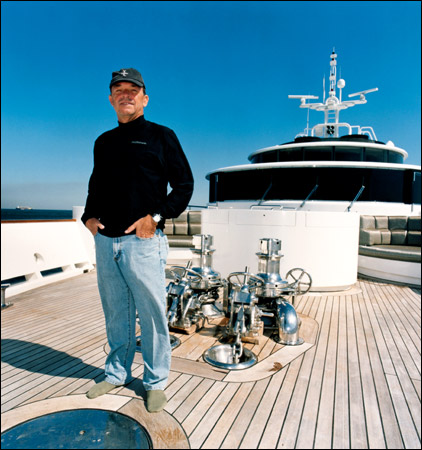

| Tim Bixseth, on a prospective yacht, casually exhibits the trappings of superwealth. |

CLUB MED |

FOR THE |

| MULTIMILLIONAIRE |

SET |

TIM BLIXSETH, FOUNDER OF THE EXCLUSIVE YELLOWSTONE CLUB, IS TRAVELING THE WORLD IN SEARCH OF SCOTTISH GOLF COURSES, FRENCH CHATEAUS AND ISLAND RESORTS. HE WANTS HIS SUPERRICH CLUB MEMBERS TO UNWIND, EVEN IF HE CAN'T. |

|||

|

TIM BLIXSETH, A 55-YEAR-OLD self-made billionaire, is rarely seen wearing a tie, or even sporting a reasonably close shave, and yet he nonetheless conveys an impression of neatness and energetic efficiency. Frequently tan, always fit and compact, he makes a point of bounding up every flight of stairs he encounters, a policy that combines his two most salient qualities: boyish enthusiasm and a strong sense of discipline. Having made his fortune buying and selling timber properties, Blixseth, in the past seven years, has shifted the focus of his considerable energy to the luxury-resort business, starting with the world's only private golf and ski resort, the Yellowstone Club near Big Sky, Mont., which he conceived of, financed and built. More recently, he has taken his luxury real-estate aspirations global, which explains his near-constant tan, a result of his personally comparing and contrasting and scooping up extravagant properties in various Sun Belts around the world. The end result of his acquisitions, a collection of nine vacation properties that Blixseth plans to call Yellowstone Club World, will essentially be an opulent time-share program for the richest of the world's rich.

Although he intends to make money from this latest venture, Blixseth has clearly taken on the project with the kind of motive a businessman can indulge once his first billion has been made: namely, he thought he would enjoy it. "I'm full time on this project," he said recently, sitting in one of the cream-colored leather chairs on his private jet, "because it's fun."

For the past six months, Blixseth has been on a galloping shopping spree. The properties that he has decided not to buy — a so-so castle in Guernsey, in the British Channel Islands ("it turned out to be a dump"), land in Mexico's Cabo San Lucas ("it's getting too Newport Beach") — have only enhanced the thrill of landing a property that makes the grade. "It's like Easter egg hunting," Blixseth said. He raised his eyebrows, as if spotting an imaginary find. "Ah, there's one." Before takeoff, he opened his laptop to start working, and as he scanned his e-mail messages, he looked, as usual, focused but highly content, as if at any moment he might start to whistle. His cheerful composure was interrupted for only moments at a time, as he impatiently waited out brief interruptions in his satellite-provided wireless Internet service, muttering his frustrations aloud and looking around wildly to see if any of the handful of business associates he had brought on board were having better luck.

Yellowstone Club World, as Blixseth envisions it, will provide housing and staff at nine luxury resorts for the several hundred members whom he hopes to start signing up in August. As many as 150 members of the club will pay initiation fees ranging from $3.5 million to $10 million; in addition, current members of the Yellowstone Club will be able to join for a lower fee. In exchange, members will have access, whenever they want, to the club's various vacation properties, all of which, Blixseth says, must have enough rooms and space to afford ample privacy if guests overlap, but also have what he calls "the wow factor" — some feature so lavish that even the extraordinarily wealthy would be impressed. A private golf club located just down the road from Scotland's St. Andrews, the historical home of the sport? That qualified for Blixseth, who purchased the club in late August. A sprawling 14th-century chateau half an hour outside Paris with amenities that include four dining areas, a fully functioning spa, a 75-foot-long pool and 1,000 acres of land? That multimillion-dollar property qualified, as did a stretch of Pacific coastline in Mexico, a resort property for which Blixseth says he paid more than $40 million. He has also purchased a resort in the Turks and Caicos islands, a famous fly-fishing lake near Cody, Wyo., and 647 acres of land near his own home in Palm Springs.

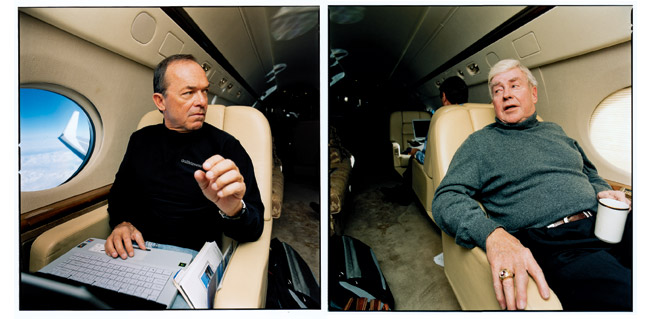

While I was visiting, the plane, a Gulfstream G550, was taking Blixseth from Bozeman, Mont., to Palm Springs, where he and his wife of 25 years, Edra Blixseth, reared their four children and where the couple still spend about a third of their time. After landing, Blixseth stayed for only three hours before heading to Mexico, where he had some meetings regarding a Mexican property he was considering buying. A few days later, he went to Turks and Caicos for dinner with a government official. When on the plane, Blixseth, if he wasn't sleeping, was either conducting business on the aircraft's phone or plowing his way through e-mail messages (all three of his private jets have wireless Internet access). Oddly, for someone who is in the business of providing world-class recreation for the wealthy elite, Blixseth is not one for leisure — at least not in the way most people think of leisure: a break from the sales pitch, the computer, the management of others' needs. "I'm not very good at vacation," Blixseth admitted, his eyes trained on his computer screen. "About four days, and I'm ready to go."

Then again, he has found a way to make the world's choicest environs, in effect, his workplace. "To me, what I do is a vacation," he said, clicking through e-mail messages, his sentences short, practically verbal telegraphs, perhaps to make for more efficient multitasking. "Every day. Fly on a private plane. Land in California. End up in southern Mexico for dinner.. . .I've got to go to St. Andrews and play golf with customers for a week? That's a vacation. Or I gotta go on to Mexico for a week and hang out on the boat and host some people? That's a vacation."

If work feels like play for Blixseth, it only follows that play — sports, in particular, but friendly competition of any kind — be taken as seriously as any $20 million real-estate deal. The former U.S. congressman and cabinet member Jack Kemp, a close friend of Blixseth's and a guest aboard his plane that day, recalled his friend challenging him to a ski race down the Yellowstone Club's 10,000-foot Pioneer Mountain. Kemp said he had to force himself to slow down, even though it meant forfeiting the race, when it became apparent that Blixseth, who was charging forward in a tuck all the way down, was prepared to put them both in considerable peril rather than lose. "I wanted to win," said Kemp, a famed competitor himself, both as a professional football player and a vice-presidential candidate. "But he was maniacal."

Edra Blixseth, who was a burgeoning hotel entrepreneur when she met her husband, says theirs is a close family and also a competitive one. "Tim doesn't like to lose, so when we play golf and I beat him, he's not thrilled," she told me with a dryness of tone that conveyed extreme understatement. The couple's home in Palm Springs is situated alongside their private, P.G.A.-quality, 19-hole golf course (the 19th is for playoffs). Once, not long after her husband lost one game too many to her, Edra recalled, "I got home from a short trip and suddenly there are sand traps right where my balls normally land."

BLIXSETH IS A NATURAL-BORN marketer. Growing up poor in Roseburg, a rural town in southern Oregon, he scanned the want ads as a teenager, buying raw materials and repackaging them as something more obviously useful — for example, picking up some cheap donkeys and reselling them as pack mules. At age 18, he made his first small fortune in timber, putting down $1,000 on a property that a nearby timber company coveted but couldn't buy because of a rift with the original seller. He promptly sold his contract to the timber company and walked away with a $50,000 profit, enough to worry his father, a minister in a small church, that he had engaged in criminal conduct of some kind. "I thought I could retire," Blixseth says.

THE CLUB'S VACATION PROPERTIES MUST HAVE WHAT BLIXSETH CALLS 'THE WO FACTOR' - SOME FEATURE SO LAVISH THAT EVEN BILLIONAIRES ARE IMPRESSED. |

At the time, Blixseth's ambition was to make it as a songwriter, and he started driving back and forth between Roseburg and Hollywood. To get by financially as he struggled with his music career, when he came home he would spend eight hours a day at the courthouse, researching possible timber deals, trying to pair, as he put it, "a willing buyer together with a willing seller." It didn't necessarily take money to make money, he understood; it took knowledge to make money, knowledge that someone had property that somebody else needed but had not figured out how to get, or did not know existed. By 25, he had formed a small company and made his first millions, taking out loans to acquire timber properties and then essentially gambling over and over that he would be able to sell off the land at a vast profit. When he was in his mid-30's, timber value plummeted and interest rates exploded, and he went bankrupt.

Within a few months, though, he made a few deals and was back on his feet. At this point, he says, he realized: "You didn't have to be the in-between guy. You could just own it. And nothing increases values like ownership." When he turned 40, he sold his share in another timber company that he had successfully built up and moved away from timber and toward real estate. Timber, as a business, he now considers relatively boring: the property is worth only as much as the crop that grows on it. But real estate, that's a creative enterprise, one that requires taking a property and developing it, creating added value — or in the case of the Yellowstone Club, a near-fantasy of luxury and privacy. "The Yellowstone Club," says Blixseth, "is turning donkeys into pack mules."

|

Hospitable Skies |

Blixseth, left, and Jack Kemp, far right, aboard Blixsth's private jet. |

The Yellowstone Club golf and ski resort arose out of one of Blixseth's savviest real-estate purchases: $24 million worth of private land parcels scattered throughout the Gallatin National Forest of southwest Montana, about 130,000 acres in all, that he and some business partners acquired in 1992 from the timber company Plum Creek. The Nature Conservancy had been trying to raise the money to buy the land — Ted Turner pledged $10 million toward the cause, perhaps because he also has vast property in the area — but when the Nature Conservancy's deal fell through, Blixseth and his partners swooped in and purchased it. Within a year, the government made a deal to buy 100,000 acres of the property from the partnership, because it contained valuable protected wildlife habitat. From that deal, Blixseth made a handsome profit, and he bought out the remaining 30,000 acres from his partners.

In the late 1990's, Blixseth started developing 13,400 acres of the Montana property as a ski resort, originally planning to use the land as a private site with a golf course and a few ski lifts for his family. But when he sensed interest from friends, he started thinking bigger, eventually building eight lifts and three dining lodges, conceiving the spot as an exclusive locale that eventually became the Yellowstone Club.

The club now has 250 members, each of whom paid $250,000 to join and committed to building or buying a property on the resort. At first this amounted to a $2 million to $3 million investment, although there are homes currently selling there for as much as $12 million.

The service at the Yellowstone Club is so attentive as to feel almost watchful. Experienced hotel managers whom Blixseth has recruited roam around the property in S.U.V.'s, conducting strategy sessions with one another via walkie-talkie on how to arrange for a guest's speedy checkout or talking with the ski patrol to make sure that homeowners' private ski-ways have been tidied up on blustery days. Ski Magazine reported that the trails are "meticulously groomed and. . .comparable to Big Burn at Snowmass or Vail's Lionshead — without all the people." Even if Blixseth reaches his ultimate membership goal for the ski resort — 864 members, no more, no less — at peak season there will still be fewer people on the mountain in a week than, say, Deer Valley sees on a slow midweek morning. President Gerald Ford's former chief Secret Service officer runs security operations in the gated property, providing a sense of safety for the club's highest-profile members, among them Bill Gates and former Vice President Dan Quayle. (Members need to be invited to join, and celebrities, for the most part, have not been.)

To Blixseth's credit, his oversize ambitions do not stop at real-estate development. He and his wife help finance and run Palm Springs' Shelter From the Storm, which not only provides unusually long-term housing and education for abused women but also provides housing for the administrative staff — a simple but generous solution to the challenge of providing social services in an expensive real-estate market. When the population of Big Sky started to boom, Blixseth offered to contribute $1 million toward the construction of a new high school. And in response to the wreckage of Hurricane Katrina, he and his wife promptly donated $2 million to Habitat for Humanity, committing themselves to helping the organization reach its goal of $100 million. Deciding that the Habitat for Humanity campaign needed a theme song, he decided to write one in a fit of late-night inspiration. The song, a catchy bit of pop patriotism called "Heart of America," written with Edra and two music-industry professionals, ultimately ended up playing on NBC as part of a joint campaign with Habitat, but NBC liked the song so much that it is now using it over promotional spots. "It always really bothered me that I never had a hit," Blixseth told me. "They can't say that anymore."

Blixseth, whose four children are now grown, often talks about the "family values" of the Yellowstone Club, although he laughs when asked if that's another way of saying that the club emphasizes Christian values. "There's one member in my religion, that's me," he said, sitting in front of a stone fireplace at his resort's Rainbow Lodge, a dining hall decorated in understated ski-lodge fashion — mounted antlers, a rug made of a musk ox on the wall, long wooden tables, a carved bar. "Based on what I went through as a kid, I don't belong to an organized religion. I'm spiritual, but I don't belong to a group." Blixseth was reared by his parents as part of what he now considers a cult, a small local group in Oregon called the Jesus Name Oneness. According to the church's tenets, he couldn't play sports, go to movies or listen to music, and the family attended church three times a week. "I thought it was absolutely a farce," Blixseth told me. "They believed they were the only 67 people on the whole planet Earth that were going to be able to go to heaven. It wasn't right. It didn't make sense. To think that 67 people out of how many at the time — three billion? — were the only ones who'd get to go to heaven: it was ridiculous."

Comparatively speaking, admitting 150 new members into the Yellowstone Club World seems almost inclusive; allowing 864 members in the ski club is downright indiscriminate.

The number of americans worth more than $30 million jumped by 10 percent last year, and according to the Mendelsohn Affluent Survey, which tracks the spending of various income groups, most millionaires splurge more on their second homes than on their first homes, frequently spending twice as much. "There's this huge appetite for families to spend quality time together and it's not happening in their primary residences," Blixseth says. Vacation, he contends, is the time when people want the home cinema, the guest house for friends, the vast common spaces and game rooms and hot tubs.

As the number of millionaires increases, it cuts into the exclusivity of high-end, but ultimately public, hotels like the Four Seasons or the Ritz. And with privacy at a premium, the desire for a truly secluded spot has only grown. Perhaps as a result, the number of people owning three or four homes has increased in recent years, as has the number of exclusive private residence clubs like Yellowstone Club World, although Blixseth's is by far the most extravagant one formed yet. (A club called Legendary Retreats, for example, charges a membership fee of $1.5 million and offers members access to homes worth an average of $8 million.)

| PROPOSED INITIATION |

| FEE FOR YELLOWSTONE CLUB WORLD MEMBERS: |

With Yellowstone Club World, Blixseth is conjuring a vision of vacation that has all of the perks of wealth — save for the thrill of acquisition he himself experiences in buying the properties. The question is whether new members will find that the convenience of the arrangement — freedom from managing a staff, overseeing renovations, paying taxes — and the uniqueness of the locations outweigh the satisfaction of putting that $3.5 million to $10 million membership fee toward something they could own for themselves. On some of the properties, members will be able to build their own homes, but on others, they will merely be members in what looks essentially like a wildly expensive time-share. (Blixseth emphasizes, however, that there's enough room and privacy on each property that the resorts will be available on demand.)

Blixseth suggested to me that Eddie Taylor, the wife of a successful liquor entrepreneur and a member of the Yellowstone Club, would be a good candidate for Yellowstone Club World: she is in her early 40's, active, with two kids. But Taylor, when I sat with her in front of a fireplace in the great room of her own 12,000-square-foot home at the Yellowstone Club, said she wasn't so sure. "It sounds really fascinating, but I don't know if it's something for us," she said. She explained that she and her husband like to return frequently to Blixseth's club in Montana, because they are avid skiers and they and their children have made close friends whom they look forward to seeing in that setting. "We love having this home, and we have our Florida home, and our boat.. . .It's just. . .you know, how many places can you go to?"

|

Blue Sky, White China |

| Place settings on Bixseth's jet, with Yellowstone Club linens. |

When I confronted him with Taylor's ambivalence, Blixseth conceded that the kind of person wealthy enough to join Yellowstone Club World is likely to have at least two homes already. But utility isn't the issue, he stressed; novelty is. Blixseth estimates that half of the original Yellowstone Club members will join Yellowstone Club World and claims that he has already received interest from some 500 prospective members. For instance, Bruce Erickson, a banker and close friend of Blixseth's, says he intends to sign up. "I might sell one of my homes," he says. "This would be just one more avenue — a new way to expand your horizons. A crème de la crème. A different kind of different."

| UP TO | $10 MILLION. |

The different kind of different would be, essentially, the extravagance of having not just a secluded villa on an extensive resort but also having the entire resort to yourself. If the Yellowstone Club golf and ski resort has a chummy feel, the Yellowstone Club World, Blixseth contends, would be less about hobnobbing and more about a unique kind of privacy. The Blixseths already have a model for that kind of lifestyle: they basically live it at their 32,000-square-foot home on their 300-acre property in Palm Springs. A drive to their estate, which they call Porcupine Creek, takes a visitor to Rancho Mirage, a relatively drab neighborhood about 30 minutes from the airport; when the gates open, however, the desert disappears and gives way to a fragrant drive lined with wildflowers, palm trees and waterfalls on either side. The 19-hole course is framed by the mountains; near the 16th hole, Blixseth and his wife have built a small carousel to amuse their grandchildren when they come to visit, as well as an old-fashioned trolley from which someone on staff provides popcorn and refreshments when the family is around. On a day when only the Blixseths' daughter and her child were there, a staff of 50 or so people could be seen buzzing around the kitchen and the laundry room, overseeing repairs on the Bellagio-like fountain in front and grooming the silent, pristine emerald green links.

Blixseth says he has paid in cash, with no help from investors, for each of the properties that make up Yellowstone Club World. He intends to make his money back off the membership fees and maintenance fees ($75,000 a year). None of his purchases, he says, have been extravagances, in terms of value. "Nobody is running around buying these properties," he says. "There's not a lot of competition out there." He is working in a realm of real estate so rarefied that it's practically outside what we consider the market. That means a buyer can get 1,000 acres 30 minutes outside Paris for what seems like a surprisingly low sum, but it also means, he acknowledges, that once he buys that property, he could have a hard time unloading it. "That's O.K.," he says. "I always have an exit strategy." The worst-case situation would be that no one signs up — and even then, he says, at least he wouldn't be in debt. The purchases won't ruin him. And for every property he can't unload, he has bought another he is sure would yield a spectacular profit in resale — say, the world-class fly-fishing lake on 3,000 acres of land he snapped up in Cody, Wyo., for all of $3.8 million. "The bigger the deal, the fewer the competitors," he says. "You should get a bulk discount."

IN ADDITION TO OFFERING access to the Yellowstone Club World properties, Blixseth intends to provide members, at cost, travel services to the various premises on three private jets, as well as the use of at least two world-class yachts. Late last month, Blixseth flew down to Fort Lauderdale to do a customary trial run on a boat for which he had just signed the deed of sale. "This boat," he said on the plane ride to Florida, "really has the wow factor. I mean, wow. It's like an Austin Powers boat."

Once on board, Blixseth bounded around, inspecting the décor, conferring with the captain about Internet access, showing off the four-story elevator, the sunroof that's actually the bottom of a top-deck hot tub, the Jacuzzis in each of the five bedrooms. Although Blixseth greeted the staff with his customary good cheer and friendly curiosity, the mood on board wasn't entirely festive — the seller's agent was watching Blixseth's reactions carefully, and it was natural to suppose that Blixseth would be bringing his own crew on, which would mean that at least a few of the people on board that day would soon be out of a job.

Blixseth announced to a prospective decorator that he wanted better deck chairs and all new linens and upholstery. He bounced onto the bed and off again, testing the mattress. A conversation about where a new flat-screen TV should be placed in the bedroom went on long enough, with enough points of view offered, that it started to feel just shy of tense. "I don't even actually watch that much TV," he said. But wait — was the boat for his personal use or for members of Yellowstone Club World? Blixseth's boats, he explained, would serve as the club's, as would his jets. In his vision, Blixseth would not be so much a hotelier to the elite as he would be a benevolent, all-powerful host sharing his finds and toys.

When it got close to lunchtime, a couple of the boat's stewards went down to the kitchen in search of sandwiches, just seconds after Blixseth had charged through the kitchen on his way to another part of the boat. "Do you think he wants to eat lunch now?" one steward asked. "I think it's too late," said the other, glancing at the tray, a couple of sandwiches missing. The ever-enterprising Tim Blixseth had already helped himself.

Susan Dominus is a contributing writer for the magazine

Copyright 2006The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times Magazine of Sunday, March 5, 2006.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |