| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted August 6, 2005 |

A Six-Day Bash Celebrates Black Theater |

|

Sara D. Davis for The New York Times |

| In Winston-Salem: theater; networking and extended-family reunion. |

| _____________________ |

By SHAILA DEWAN |

| _____________________ |

WINSTON-SALEM, N.C., Aug. 3 - An estimated 60,000 people, nearly all of them black, descended on Winston-Salem this week for the six-day National Black Theater Festival. The event, held every two years here since 1989, is a showcase for black theaters, a networking opportunity for black performers and playwrights and an extended-family reunion of sorts for the fans and celebrities who return time after time from New York, Los Angeles, Newark and Dayton, Ohio.

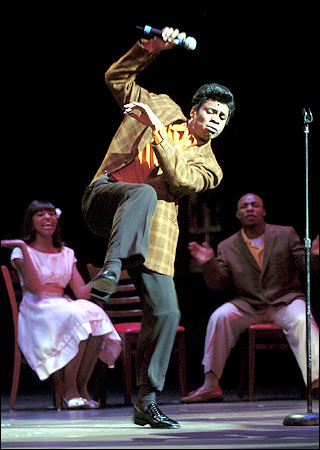

As the festival, which has a budget of $1.5 million, has grown in this city of nearly 200,000, so has its audience, and organizers estimated that $15 million would be pumped into the local economy. Visitors and local residents could choose from 40 productions, ranging from musicals like "The Jackie Wilson Story (My Heart Is Crying, Crying ... )," about the Detroit rhythm-and-blues singer; to an after-hours show, "Herotica," performed by 3 Blacque Chix, a trio of middle-aged women who talk about sex; to the Pulitzer Prize-winning play "Topdog/Underdog" by Suzan-Lori Parks; to a variety of solo shows.

| Mighty poetry jams and plays about noted performing artists. |

For a few days, downtown Winston-Salem is transformed, its streets echoing from drum circles and choked with limousines. There are African art vendors and midnight poetry jams, open-mike talent shows and nightly celebrity receptions at which the dance floors are packed until nearly dawn.

"It's incredible; everybody's energy is so high," said Daniel Beaty, 29, a New Yorker whose one-man show, "Emergence-See!," imagines the sudden surfacing of a slave ship in the harbor of modern-day New York. "We long for moments to celebrate ourselves, to have experiences that are completely positive," he added "We have a history of collective consciousness and a collective spirit."

On Mr. Beaty's opening night, he got a whooping standing ovation from an audience that included the poet Sonia Sanchez, the playwright Lynn Nottage, the actors James Avery and Ruben Santiago-Hudson and the actresses C. C. H. Pounder and Tonya Pinkins, who whispered something in his ear about mentioning him to her agent. Also present was his mentor and producer, the venerable Ruby Dee, who had first seen his show at a tiny alternative space near Times Square. These notables and others - Malik Yoba of "New York Undercover," Antonio Fargas of "Starsky and Hutch," the actress Janet Hubert - mingled easily, without bodyguards or V.I.P. sections, giving the festival the feeling of a private celebration despite the number in attendance.

"I would not want to see it in a larger metropolis," said Sandy Lindsay, a school nurse from New Jersey who drives down with her girlfriends every two years. "It would lose its intimacy." That afternoon, Ms. Lindsay and her 15-year-old granddaughter had seen a play starring Kim Fields, still best known as Tootie on "The Facts of Life," who at one point invoked the name of a famous blues singer: "Linda Hopkins, can I sing?" Ms. Fields ad-libbed.

"Yes you can, baby," answered a sonorous voice from the audience.

Much of the festival's tone is a reflection of its founder, Larry Leon Hamlin, who always wears large, flashy sunglasses (to protect others, he says, from his penetrating stare) and who was driving a new Hummer on loan for the week. Mr. Hamlin is the artistic director of the North Carolina Black Repertory Company in Winston-Salem. He started the festival to connect black theaters around the country, enlisting Maya Angelou, Sidney Poitier and Oprah Winfrey in the early years to draw attention to the project.

The success of the first festival, Mr. Hamlin said - it drew 10,000 people - helped dispel a misconception that black theaters were not professional enough to warrant grant money. "It shook loose some dollars," he added. Among the groups participating this year were the National Black Theater in Harlem, the Black Ensemble Theater in Chicago, the Walltown Children's Theater in Durham, N.C., the Black Academy of Arts and Letters in Dallas and assorted independent productions.

Mr. Hamlin, a North Carolina native who studied theater at Brown University, seems to do nothing in moderation. Opening-night festivities on Monday began outside the convention center with a purple carpet (Mr. Hamlin's favorite color) and a sold-out, $250-a-plate dinner, an awards ceremony, the first act of "The Jackie Wilson Story" and a dance party. The attire - floor-length gowns and embroidered dashikis, bow ties and spindly heels - was worthy of Oscar night.

The goings-on attract locals, too, who head downtown after work or school. Perhaps understandably, given the spectacle on the street, several Winston-Salemites said they did not plan to see any theater. But Ellen Carter, 56, a customer service worker at a nearby insurance company, said she was "a connoisseur of the arts." In 2003 she saw "The Jackie Wilson Story" three times. "Went broke," she said. "Didn't pay a bill so I could go see it again."

|

Sara D. Davis for The New York Times |

| Chester M. Gregory II in "The Jackie Wilson Story." |

Ms. Carter said two of her three grown children and several grandchildren were also festival fans, and such multigenerational attendance was not uncommon. Cynthia Mosely, 40, a mortgage closer from Florida, said her mother-in-law, a regular attendee, persuaded her to come this time with her 13-year-old daughter, Tyiesha, an aspiring actress who had already had her photo taken with Ms. Dee and spoken with T'Keyah Crystal Keymah, whom she recognized from television and the movies.

"We'll come every year," Ms. Mosely said, as she and Tyiesha pored over the schedule. "I want her to see how it really works. And it's inspiring to me."

| The feeling of a private gathering despite crowds, and Oscar-worthy attire. |

For performers, the festival is a chance for exposure to artistic directors and producers from around the country. The 3 Blacque Chix, for example, hope to market their show to a wider audience. It currently plays once a month in Los Angeles. "We want to go on tour," said Mariann Aalda, 57, a television actress and one of the Chix. "We want to go to Vegas. We'd like to see a series come out of this." Her cast mate, Iona Morris, 48, chimed in, "Residuals, royalties, retirement." At their rehearsal on Tuesday afternoon, they said they had received inquiries from Miami and New York producers attending the festival.

What precisely makes theater "black theater" is hard to say. But two threads wove their way through the festival schedule. One was the celebration of black performing artists - in addition to the musical about Mr. Wilson, there were plays devoted to Mahalia Jackson, Thelonious Monk, Dorothy Dandridge and Melba Moore (a cabaret-style show, performed by Ms. Moore herself).

The second was the pronounced rhythm of hip-hop and spoken word. Six years ago, the festival presented hip-hop theater as a distinct category. But now, its inflections are dispersed, from the show by Mr. Beaty, a onetime poetry slam champion, to "By a Black Hand," a musical about cultural and scientific achievements by blacks.

"There has always been a connection between black theater and poets," said Weusi Baraka, 34 (no relation to Amiri Baraka), who helped organize the festival's midnight poetry jams. "It was poets like Ntozake Shange or Amiri Baraka who paved the way and defined black theater at certain points in history."

The poetry jams are part of Mr. Hamlin's effort to bring in younger audiences - a challenge he shares with American theaters of every stripe, but one that he appeared to be mastering, judging from the number of prom-age theatergoers in the houses.

On Wednesday, though, the jam seemed to attract as many older patrons as younger. They filled an auditorium in the convention center and included Irma P. Hall, 70, who played Big Mama in George Tillman Jr.'s 1997 movie "Soul Food" and who sat in the front row waiting for a turn to go on.

Yolanda Wilkerson, a poet from the slam circuit in New York, delivered a poem called "Untitled and Unfinished," in which she suggested alternatives to the term "African-American," including "UPN- and WB-American" and "They'll-never-test-diseases-on-me-American."

But before she began, she looked around the room and gave a big smile at the nearly all-black audience. "I haven't been here in four years," she said, "and I don't get to see black people that often."

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, TheArts, of Saturday, August 6, 2005.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |