| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted June 3, 2007 |

| A Nation's Lost Holocaust History, Now on Display |

|

|

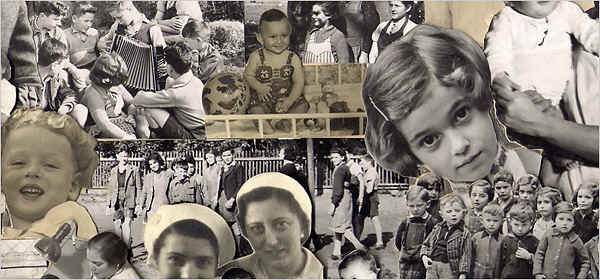

Harald Wendelin/Jewish Community Vienna |

|

| One of several Jewish Community Vienna collages created about 1940, probably to help foreign fund-raising. | |

By MARJORIE BACKMAN |

WHEN Israelitische Kultusgemeinde Wien, or Jewish Community Vienna, decided to sell a vacant building in the summer of 2000, two employees were sent to look for any archival material that might have been left behind.

What they found exceeded any historian’s dream: Stacked floor to ceiling in two rooms of one apartment sat some 800 dusty boxes containing, among other things, about half a million pages of detailed records of the community during the Holocaust — archives not known to have survived.

“Opening each box was extremely exciting,” said Lothar Hölbling, the chief archivist and one of the discoverers. “Eight hundred excitements.”

Now, after seven years of quiet work reordering, preserving and microfilming the archives — a joint project of Jewish Community Vienna and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington — the documents are about to be officially unveiled with a presentation at the museum on Thursday, followed by an exhibition, opening on July 3, at the Jewish Museum Vienna.

When combined with community records stretching back to the 17th century that had been shipped to Israel in the 1950s, the Vienna cache makes up one of the largest Holocaust archives of any Jewish community, some two million pages. With it historians will be better able to understand how the Holocaust unfolded and provide a window into the daily life of Vienna’s Jews. The archives of Jewish Community Vienna, the representative body of the city’s Jews, will also be of great help to families in uncovering exactly what happened to their relatives.

“For most of the last six decades, people believed that one could not study the action of Jews in the Holocaust period because the Nazis systematically destroyed the records of Jewish communities and organizations,” said Paul Shapiro, director of the Holocaust museum’s Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies. “Most Holocaust scholarship has been written based on the documentary record created by the perpetrators of the Holocaust.”

The Vienna archives, in their entirety, are believed to be the largest collection of material about a Jewish community in the German-speaking world, Ingo Zechner, director of the Vienna group’s Holocaust Victims’ Information and Support Center, said. Indeed, Vienna once had the third-largest Jewish population in Europe.

A survey of Vienna’s pre-Holocaust records illustrates the community’s diversity: Jewish cultural organizations, welfare societies, chess clubs, groups of Jewish soldiers from World War I, Zionist groups — even monarchist clubs are represented, Mr. Zechner said. A 1927 letter from Sigmund Freud declared his 1926 income of 50,000 Austrian schillings and the tax he expected to pay the group.

Some of Vienna’s Holocaust-era files can already be viewed on microfilm at the Holocaust museum in Washington and at the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People in Israel. And, according to plans arranged with Simon Wiesenthal before his death, a proposed Vienna Wiesenthal Institute for Holocaust Studies will unite under one roof Mr. Wiesenthal’s Nazi-hunting files with the Jewish Community files and will serve as a research institute for visiting scholars and a showcase for themed exhibitions.

After the Nazis annexed Austria in 1938, they began disbanding virtually all Jewish groups. Two months later the Nazis reinstated Jewish Community Vienna, Mr. Zechner said, enlisting it to help carry out their initial plan, which was for Jews to depart Austria after paying fees and leaving behind most of their property.

Discovered within the Vienna apartment were card indexes, produced by the community’s emigration office, with the names of 118,000 Jews from families that had sought its assistance to emigrate in 1938 and 1939. These indexes were the key to sorting through thousands of emigration questionnaires already stored in Jerusalem.

The questionnaire, filled out by the head of a household, solicited four pages of detail about family and economic status, references and contacts abroad — pertinent information for those seeking visas.

“A Jewish community official would make a house visit and describe the living conditions,” Anatol Steck of the Holocaust museum said. In many cases it is now possible to trace every administrative step, from someone’s first contact at the emigration office to when the family boarded a train or a ship, Mr. Zechner said.

The archive also contains thousands of letters, many related to emigration issues. “They would assist families in working through the bureaucratic maze of getting out of the country,” Mr. Shapiro said. “They also made a calculation of which families needed cash.”

____________ |

|

| Restoring the memory of Austria's Jews with 800 boxes of records. | |

____________ |

Jewish Community Vienna encouraged Jews to learn new skills, like farming and mechanics, so they could be placed abroad, Mr. Steck said. When the psychiatrist Viktor Frankl, the founder of existential analysis, filled out an emigration questionnaire in 1938, Dr. Frankl wrote by hand in German: “I’m living with my father, a federal retiree. My income from my medical practice is so little, I will have to close my medical office.” Asked if he had been trained in a new profession, he wrote, “I’m about to learn the craft of house painting.”

Dr. Frankl received an immigration visa to the United States but forfeited it so as not to leave behind his parents. He, his wife and his parents were deported in 1942 to concentration camps; only Dr. Frankl survived, writing of his Auschwitz experiences in “Man’s Search for Meaning.”

For Jews who perished, Mr. Steck said, “the questionnaires are like the last testament of the victims.” Ultimately, two-thirds of Vienna’s Jewish community survived the Holocaust, but more than 65,000 Austrian Jews were murdered.

Walter Feiden, 79, of New York City, is the only survivor of his Viennese family. His father, Moses, went to the community organization’s offices to research names and addresses in phone books before securing affidavits of support from two American strangers: a Jewish manufacturer and a district attorney named Feiden. Yet the United States consulate rejected Moses Feiden’s visa request after learning he was born in Poland, not Austria. On Oct. 15, 1941, the Feidens were deported to the Lodz ghetto, where Moses died; Emilie, Walter’s stepmother, was transported to Chelmno and gassed.

Just last month Mr. Feiden learned of a letter found in the archives indicating that right before the family’s deportation, the Dominican Republic had approved visas, and that a Jewish community official had asked the Gestapo to strike the Feidens from the deportation list.

|

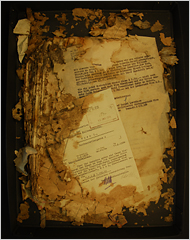

Jewis Community Vienna |

| Holocaust-era records found in Vienna are providing a wealth of information about Austria's Jews. |

“This is a shocker to me,” Mr. Feiden said. “There’s no way to get back what I lost,” he said, adding that he was glad to know the new information “to the extent that it proves to me that my father tried even harder.”

Also found in Vienna: the lists for 45 deportations, each naming about 1,000 Jews scheduled for transport in 1941 and 1942 to destinations like Auschwitz, Theresienstadt, Lodz and Minsk. Some of these locations were known then as Jewish ghettos. Not as widely known, however, was the fact that after a certain time, they became transfer points to death camps.

Raul Hilberg, author of “The Destruction of the European Jews,” viewed the deportation lists in the archives last year. “The most troublesome question which occurred to me is, who prepared the list?” he asked. “Who picked these names to begin with? Whenever I asked anyone at all, I got the same answer. The community did not prepare the list. On the other hand, the Gestapo people after the war insisted that they prepared no lists. But someone had to choose the people and look up the addresses.”

The records found in Vienna are also being used to help families file restitution claims. The Holocaust Victims’ Support Center was founded in 1999, the year after Austria began serious discussions about compensation for looted artwork, slave labor and stolen property.

The tireless efforts of Mr. Zechner, 34, and Mr. Hölbling, 36, to reorganize the files are noteworthy because neither is Jewish, nor is most of the center’s 12-person staff. Mr. Zechner said the involvement of non-Jews was partly due to Austria’s increased openness to reflecting about the Holocaust in the years since revelations emerged about the Nazi past of Kurt Waldheim, the nation’s former president.

For Mr. Zechner, a historian and philosopher, a major motive in working for the organization “was to understand what happened during the Holocaust and how the Holocaust affects our present life.”

Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, The Arts, of Saturday, June 2, 2007.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |