| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted August 23, 2003 |

| A Communist Life With No Apology |

| By SARAH LYALL |

LONDON, Aug. 22 — Born in 1917, the year of the October Revolution, the historian Eric Hobsbawm has lived through much of "the most extraordinary and terrible century in human history," as he describes it, from the rise of Communism and fascism to World War II, the cold war and the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Advertisement

Recent events, he says, "fit in with the gloomy picture" he has had of world affairs for the last three-quarters of a century.

But for an unapologetic pessimist, Mr. Hobsbawm is remarkably robust, bordering on cheerful.

As he describes in "Interesting Times: A 20th-Century Life" (Pantheon), his new memoir, Mr. Hobsbawm has overcome considerable odds, including a fractured childhood in Weimar Germany, to become one of the great British historians of his age, an unapologetic Communist and a polymath whose erudite, elegantly written histories are still widely read in schools here and abroad.

He turns his analytical historian's eye on himself, examining with wry, rich detail the history of the century "through the itinerary of one human being whose life could not possibly have occurred in any other," he writes. The title's twin meanings — interesting times, according to the old Chinese curse, inevitably carry tragedy and upheaval, too — neatly capture the tensions between his personal history and his life as a historian.

"Do you remember what Brecht said — `Unlucky the country that needs heroes'?" Mr. Hobsbawm asked. "From the point of view of ordinary people, uninteresting times, where things aren't happening, are the best. But from the point of view of a historian, obviously, it's completely different."

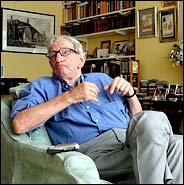

Mr. Hobsbawm, a gangly 86-year-old with thick horn-rimmed glasses and an engagingly lopsided smile, spoke in his living room in Hampstead, long the neighborhood of choice for London's leftist intellectuals, in between sips of coffee. The room was lined with books; the front hall was full of the toddler paraphernalia that comes when one's home is a destination of choice for grandchildren (he has three). The telephone rang constantly as various family members and friends called to discuss plans that Mr. Hobsbawm invariably said would require further consultation with his wife, Marlene, who was out for the morning.

|

Steve Forrest/Insight, for The New York Times |

| The historian Eric Hobsbawm, at home in London, turns his analytical eye on the times he has seen. |

Mr. Hobsbawm is that unlikeliest of creatures, a committed Communist who never really left the party (he let his membership lapse just before the collapse of the Soviet Union) but still managed to climb to the upper echelons of English respectability by virtue of his intellectual rigor, engaging curiosity and catholic breadth of interests. He is an emeritus professor at the University of London and holds countless honorary degrees around the world, from Chile to Sweden.

Yet he will always be dogged by questions about how he can square his long and faithful membership in the Communist Party with the reality of Communism, particularly as it played out under Stalin. In "Interesting Times," he denounces Stalin and Stalinism but also praises aspects of Communist Russia and argues that in some countries, notably the former U.S.S.R., life is worse now than it was under the Socialist system.

Some people will never forgive Mr. Hobsbawm for his beliefs. In an angry review of his new book in The New Criterion, David Pryce-Jones said that Mr. Hobsbawm was "someone who has steadily corrupted knowledge into propaganda" and that his Communism had "destroyed him as an interpreter of events."

"Interesting Times" has gathered mostly glowing reviews across Britain. But the book again raises the problem that even Mr. Hobsbawm's admirers find dismaying.

In The Times Literary Supplement, the historian Richard Vinen said that "Interesting Times" does not give a satisfactory explanation of its author's motivations. "The closer that he comes to such questions, the more confusing he becomes," Mr. Vinen wrote.

Mr. Hobsbawm does address the issue in a section explaining why he did not abandon Communism in 1956 when Nikita S. Khrushchev's electrifying denunciation of Stalin sent waves of revulsion at Stalin's crimes through the worldwide movement. But while many of his colleagues resigned from the party in horrified protest, Mr. Hobsbawm did not.

He says he was "strongly repelled by the idea of being in the company of those ex-Communists who turned into fanatical anti-Communists." More important, perhaps, was the childhood he spent in interwar Germany, where he was part of the generation "tied by an almost unbreakable umbilical cord to hope of world revolution, and of its original home, the October Revolution, however skeptical or critical of the U.S.S.R.," he writes.

Asked the same question in his living room, Mr. Hobsbawm sighed. It is a question he is always asked. "Let's put it this way," he said. "I didn't want to break with the tradition that was my life and with what I thought when I first got into it. I still think it was a great cause, the emancipation of humanity. Maybe we got onto it the wrong way, maybe we backed the wrong horse, but you have to be in that race, or else human life isn't worth living."

Communism, he said, was much more than Stalinism and meant different things around the world in Spain, in Italy, in South America, in South Africa, for instance. "The idea that the only thing about this movement was that you were for the Soviet Union and that when you then discovered how awful Stalin was that you should have left is not a historic way of looking at it," he said.

__________________ |

| Respectability by virtue of intellectual rigor. |

__________________ |

Mr. Hobsbawm's book is about far more than his Communism, though politics and life to him are symbiotic. Born a Jew in Alexandria, Egypt, to an English father and an Austrian mother, he lived until his early teens in Vienna and then in the disastrous dying days of Weimar Germany. Both his parents died by the time he was 14. His father, struggling hand to mouth to make a living, collapsed one day on the doorstep of their home. His mother died after a wasting illness some two years later.

Mr. Hobsbawm fled into himself, finding relief in the life of the mind. "Clearly it marked me very deeply, but I was covered to some extent because I had, as it were, my private escape into curiosity, into fantasy," he said. "It probably also left me with an unwillingness to be too outgoing. I kept a lot of my troubles to myself."

His youth, particularly as Hitler's fascists began their rise to power, propelled him into Communism and into a lifelong sympathy for revolutions, for contrary thinking, for the ideal of revolutionary utopia. This took root in many ways, from his love of jazz (for a time, he was the jazz critic for The New Statesman) to the wide range of subjects in his books.

He is best known for his books surveying the history of the world since 1789: "The Age of Revolution" (1962), "The Age of Capital" (1975), "The Age of Empire" (1987); and "Age of Extremes" (1994). He commands a loyal following, particularly in Latin America. The author Julian Barnes appeared with him at a literary festival in Parati, Brazil, and in a recent article in The Guardian described how Mr. Hobsbawm was accosted by fans demanding his autograph as he walked around town.

As a youth, Mr. Hobsbawm moved to England with an aunt, eventually earning a place at King's College, Cambridge, on the strength of his obvious brilliance. He later became a lecturer and then a professor in Birkbeck College in London.

Famous friends, colleagues and public figures flit in and out of the pages of his book. Arthur Schlesinger Jr., E. M. Forster, Che Guevara (for whom Mr. Hobsbawm was once an impromptu interpreter, though he was no admirer of Che's guerrilla strategy) all make appearances, along with scores of others. Mr. Hobsbawm also describes the inner workings of the Historian's Group in the British Communist Party; the almost physical agony that Communists in Britain suffered when the truth about Stalin became clear; and various debates in the Labor Party, which has occasionally turned to him for advice.

"If anything, I was an extremely right-wing Communist and generally attacked by the leftists, including the leftists in the Labor Party," he said.

His travels took him all over the world, and along the way, he picked up the ability to speak German, French, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese and to read Dutch and Catalan. Mr. Hobsbawm visited the Soviet Union only twice, finding that it was dispiriting and that he had a much greater affinity with Communists elsewhere. He remains as busy as ever, preparing papers for conferences abroad in the next year.

Mr. Hobsbawm wrote his book, he writes, not for "agreement, approval or sympathy" but for "historical understanding," as a way to explain himself and his thinking. It ends on a pessimistic note, with a discussion of Sept. 11 and America's thrusting new role in the world.

The Sept. 11 attacks, as horrific as they were, were not comparable as a crisis either to World War II or to the cold war, he said, and the United States made a grave mistake in reacting the way it did.

"At present, pessimists like myself look forward to a very disturbed next 10 or 20 years, very largely because of the present policy of the people who are in charge in Washington," Mr. Hobsbawm said.

Over his many years and against considerable odds, Mr. Hobsbawm has somehow maintained his belief in human resilience, in man's ability to live through the most appalling personal and public tragedies and still go on. Speaking of the blitz, he said that survival during that time required a suspension of fear, a willful pushing aside of reality.

"Once you actually lived under bombardment, for instance, as Great Britain did, you recognized that you could survive," he said. "I think that human beings can manage to square a lot of things. The truth is that except for short periods, ordinary life goes on, so long as it's allowed to."

Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Arts & Ideas, of August 23, 2003

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |