| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| More Books and Arts |

| Posted Tuesday, August 10, 2010 |

|

I'm American. And You? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

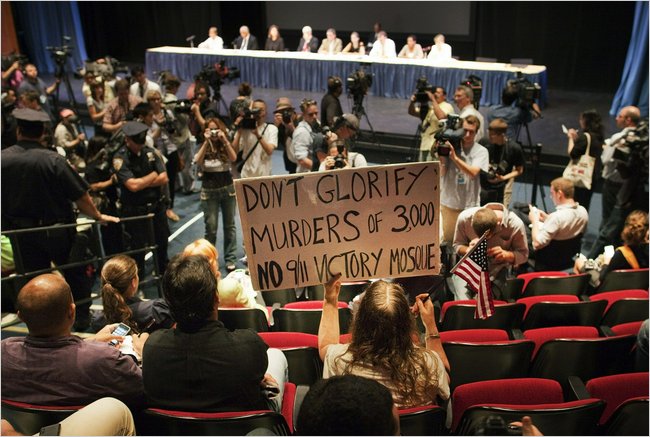

TIM SLOAN/AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE - GETTY IMAGES |

|

| Several Republican senators are calling for the repeal of the 14th Amendment, which gives citizenship to those born on American soil. |

|

By MATT BAI |

|

|

MICHAEL NAGLE/GETTY IMAGES |

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |